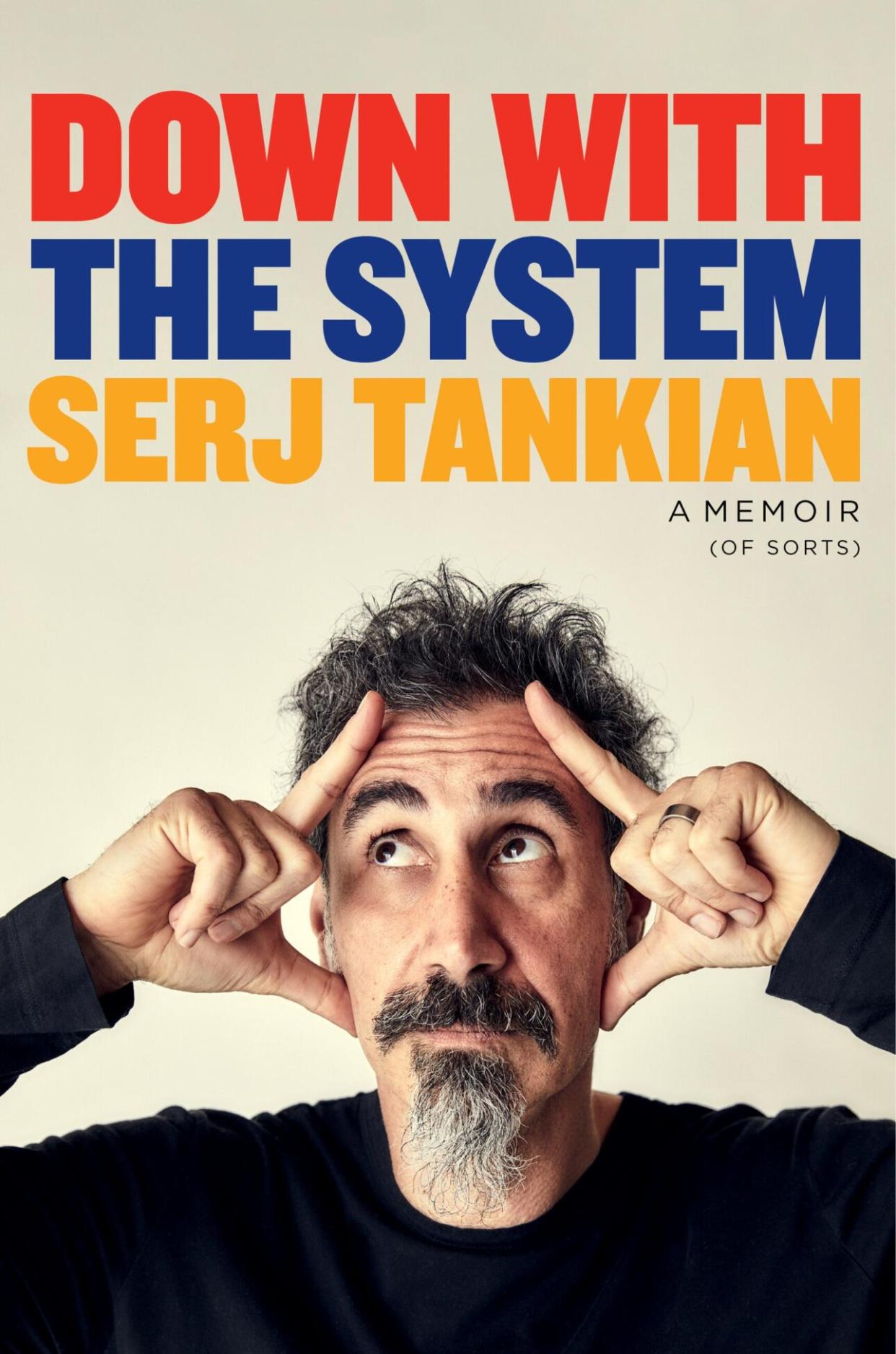

‘Talking About Myself Is Fucking Boring as Shit’: Serj Tankian on His ‘Memoir (of Sorts)’

Serj Tankian was just 7 when he crouched inside his trembling bedroom walls, protectively hugging his little brother Sevag, as bombs exploded outside. And while the Beirut-born Armenian escaped to California, his new life presented its own battles, from immersion challenges to family lawsuits and depression.

More from Spin:

System of a Down Lead Historic Golden Gate Park Concert Lineup

As Nagorno-Karabagh Humanitarian Crisis Worsens, Serj Tankian Drafts Open Letter Urging Intervention

Today, there’s little sign of the hardships of Tankian’s youth as he lights up, sharing how his nine-year-old son, Rumi, just composed his first song, and eagerly quizzes me on the best Indian food in my native Auckland, New Zealand, where he lives part-time. Fresh from SOAD’s Sick New World Festival performance, Tankian’s pumped to release new solo music and add “café owner” to a list that already includes musician, painter, poet, activist, composer, and filmmaker.

I can’t help wondering how Tankian, 56, turned his life around so remarkably. Maybe it’s the meditation he praises on page 162 of his new book, Down With the System. Maybe “survive and thrive” is imprinted in his DNA by grandparents who lived through 1915 Armenian Genocide. Maybe it’s the serenity he found in Auckland. Or maybe it’s the fierce drive to fight for justice that was instilled by the unjust terrors his family lived through. Ultimately, that’s what seemingly fuels every ounce of Tankian’s existence.

“I’d love to wake up and not be an activist,” he tells me, sitting in an under-construction office above his Kavat Coffee Shop, opening this summer in Los Angeles. “But that’s impossible with the unjust world we live in. And my activism’s so intertwined with my art and music that I wake up excited. I was excited to write a book because through its promotion I can talk about Armenian history and other injustices. After 30 years, just talking about myself is fucking boring as shit. It’s stupid, right?”

That’s why Tankian’s book’s labeled “a memoir (of sorts)” and amid the gripping historical anecdotes, he explains how understanding that background is key to understanding him.

Of course, there’s no shortage of System of a Down stories, given the alt-metal group commemorating 30 years together. Formed in Glendale, near Tankian’s café, he and Armenian-American bandmates Daron Malakian, Shavo Odadjian, and John Dolmayan topped the charts and toured the world while pushing for awareness and recognition of the 1915 Armenian Genocide and other causes.

Tankian discovered heavy metal at an Iron Maiden gig at 17, but it wasn’t until he sunk into depression while helping his parents through an all-consuming 10-year business lawsuit that he turned to a Casio keyboard for escapism.

“While my fingers were on those keys, the rest of the world faded away into a fuzzy background,” he writes in Down With the System, released on May 14 on Hachette Books. “It was like being cocooned in a warm netherworld, insulated from the everyday shit that could drag me down.”

Music made Tankian feel “alive,” so he started playing in bands. Although he entered other fields, like software development, Tankian surrendered to full-time music after remembering how his father, Khatchadour, sacrificed musical aspirations following a jarring conversation en-route to an oud class.

“[Another musician] told my father tales of endless traveling, relationships that fell apart, money struggles, lonely nights tossing and turning in strange beds, watching fellow musicians numbing themselves with alcohol and drugs,” Tankian writes. “My father took it all in. At the next stop, he got off the bus.”

Following SOAD’s rise, eventually Tankian, too, wanted off the bus. At least, the tour bus. His euphoric onstage highs were eclipsed by offstage isolation, monotony, and sleep deprivation. Meanwhile, studio tension grew as he began writing more music, but found his contributions sidelined as Malakian strived to retain creative control.

“I was desperate to collaborate, to be creative, but everything within the band felt rigid and inflexible,” Tankian writes in his book. “If I mentioned that I had a song I wanted us to take a crack at, Daron would never outright refuse, but it was always ‘Let’s work on that one next week,’ or ‘How about we finish up this batch of songs first?’ We rarely ever seemed to get to my songs.”

Tankian continues that while he became frustrated and discouraged, he wasn’t in the “emotional headspace” to fight back, so the group continued the sessions, which lead to their fourth record Mezmerize in 2005, followed by 2006’s Hypnotize.

By the time they got together to talk about another record around 2018, Tankian didn’t feel comfortable repeating the pattern of previous album sessions. In Down With the System, he recalls presenting a “bullet-pointed manifesto,” listing the terms on which he would record new music. The first was that he and Malakian contribute an equal number of songs. The record soon crumbled.

Asked whether he can envision Malakian (who has Tankian’s book but hasn’t yet commented on it) ever relinquishing enough creative reins for Tankian to attempt a new album again, he’s tactful.

“Daron defines himself as the primary songwriter for System. It’s important to him. Will that ever change? I don’t know. But I don’t see it negatively anymore because I understand it better. That doesn’t mean I have to create music in that capacity. As for a future System record, the saying goes, ‘Nobody knows!’”

He adds that he never saw himself committing to any group forever. “Bands aren’t meant to do the same thing over and over,” says Tankian, who’s done solo records, film scoring, orchestral collaborations, art exhibitions, and executive produced the Armenian film Amerikatsi. “I never thought bands should last forever because that’s a detriment to the art. It creates redundancy and repetition. Sure, there’s exceptions, and I don’t want to sound like a dick and take away from what people love to do, but I think most artists should just make x number of records. That said, I love seeing artists collaborate, like when Chris Cornell did Temple of the Dog.”

Cornell became a close friend after the two met through a doctor pal. Tankian says the rocker’s death “broke [his] heart.” He recalls how they worked together on the 2016 film The Promise and hung out everywhere from Paris to Auckland. “He visited me in New Zealand, and we had a beautiful day fishing and enjoying the countryside. He got to relax.”

Relaxing in New Zealand has become vital to Tankian, who felt an overpowering draw to the country in his 20s. SOAD had released their second album, Toxicity, when Tankian awoke to 9/11. Toxicity hit No. 1 the same day—a “cosmically insignificant” achievement as the world mourned. In days following, Tankian penned an essay that he described to The Guardian as “a sober analysis of the failure of American foreign policy to rein in extremism”; however, it led to death threats and being urged to “go back home.” After 26 years in America, Tankian suddenly felt like “a man without a country.”

Four months later, that changed as SOAD arrived in Auckland for a music festival. Gazing out from the towering Metropolis Hotel, Tankian was mesmerized by shimmering blue waters and rolling hills. “Calmness and peace overcame me,” he says. “It was an intuitive sense of belonging I’d never felt elsewhere.”

Tankian also felt something he was stripped of in Beirut and, at times, L.A. “I felt safe. The US was embroiled in the Iraq War, but in New Zealand, front-page news was, ‘Dolphin lands on woman on boat.’ And the foreign minister was critical of the war, which was a breath of fresh air.”

Returning annually, Tankian obtained residency around 2005. By then he had become “enchanted” by now-wife Angela, who had never heard of SOAD, at a friend’s birthday. “We’re celebrating our 20th meeting anniversary,” Tankian adds with a grin. They later began dating, but the early days were tough, with Tankian increasingly in Auckland while Angela worked as a stylist in L.A. Persevering, they wed in 2012 then welcomed Rumi.

Tankian beams with pride describing Rumi’s musical side. “He loves System! He’s really into rock and metal, and I’ve been helping him with mild composing. He recently came into my studio, looked at the keyboard, and said, ‘Dad, can I play?’ I said, ‘Sure, bro.’ He wrote a song, was very proud, then wanted to write another one.”

Tankian’s parents also love his second home. He chuckles at how his mom Alice remarks the landscapes make her “feel like someone’s painted my eyes green.”

Providing loved ones with such a sanctuary is a blessing, given what Tankian faced around Rumi’s age. However, his childhood wasn’t all doom and gloom. In his book, he fondly chronicles Beirut beach days that concluded with devouring fries while sleepily counting blurred street lights on the drive home. That “hypnotizing” calm is what Tankian later sought through meditation and likely finds during New Zealand summers picnicking beachside with fish and chips.

While Rumi’s young, Tankian educates him on family history. “That’s a challenge when talking about genocide, but I also discuss other people’s plights so he can understand a simple meal’s a privilege. Kids are like, ‘Whatever!’ You have to be repetitious.”

Tankian also continues sharing his culture Stateside, like with his Armenian coffee brand Kavat. The aroma of coffee nostalgically transports him back to Beirut, where he and Sevag raced around their apartment while Alice chatted with visitors over fresh brews.

Nestled among a bar and pizza place in L.A.’s Eagle Rock neighborhood, Tankian’s own coffee spot will also house his artwork, boxes of which sit amid the construction, awaiting his autograph. There’s also a sun-soaked patio, which would be a perfect setting for Tankian to launch his upcoming EP Foundations. The “musical retrospective” features songs from different chapters of his past. The first single, “A.F. Day,” is out May 17—it’s an “angst-driven” song written for SOAD. “I kept the demo vocals because I can’t reproduce that sound from 30 years ago!”

Vocals and band dynamics may have changed, but Tankian’s thankful SOAD’s bonds are everlasting. The group’s “acrobatic, high-energy” performances feed him like nothing else, so with or without new albums, chances are they’ll continue performing. Next up is a gig with Deftones.

“Our shared heritage as Armenian-Americans, shared respect for each other, and knowing each other’s families means we’re still able to perform and have fun together despite creative differences. I love the guys and the music. I just don’t want to repeat it ad nauseam, so it becomes redundant for me, like touring does.

“Maybe it’s because I came to music later in life and becoming the biggest rock band wasn’t ever on my mind,” he continues. “It was about becoming an artist and dispensing truths. But I’m amazed and grateful we still have this respect, we’re still friends, and still able to do whatever we agree upon doing together. It’s special.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.