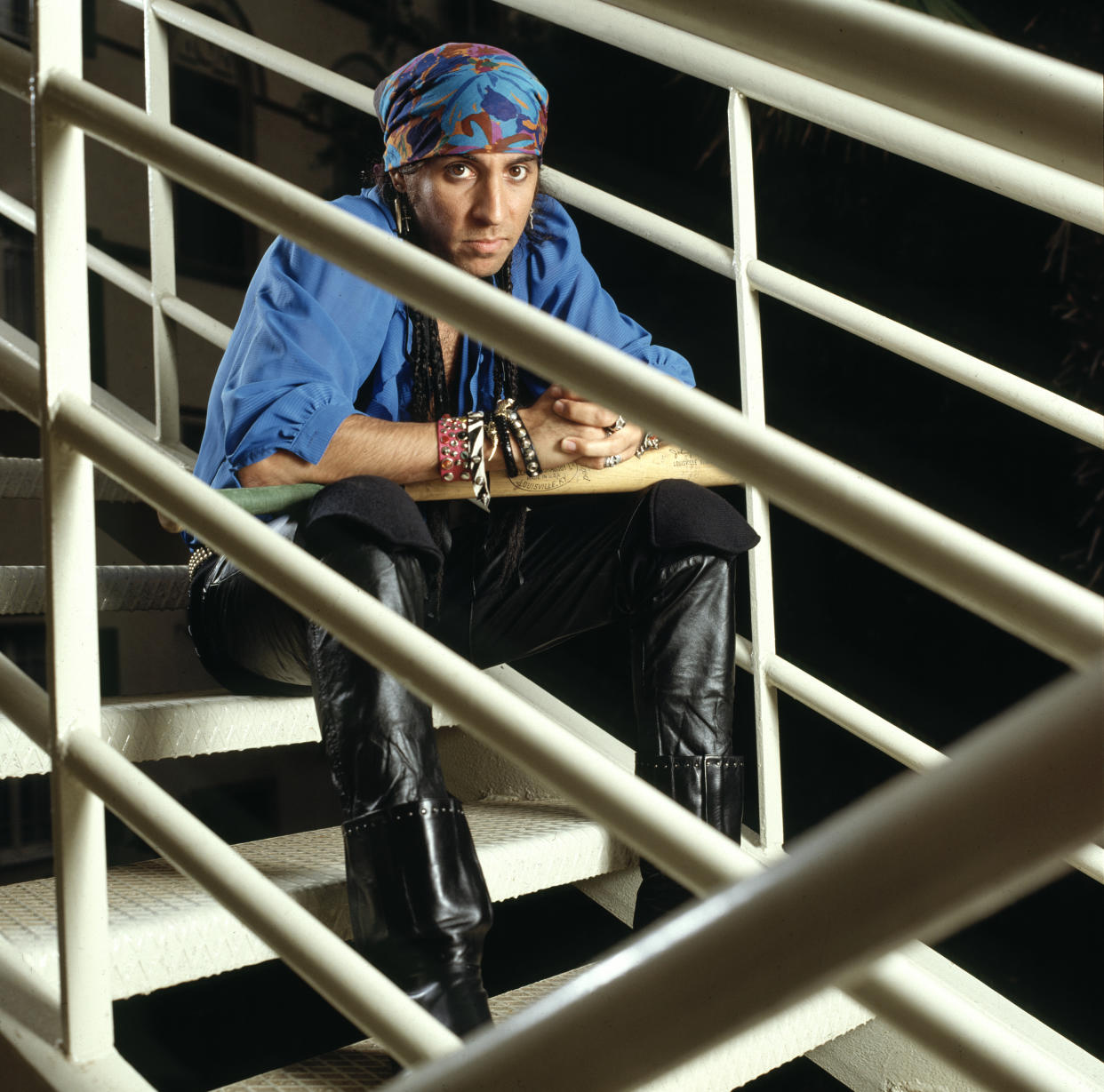

Steven Van Zandt recalls leaving the E Street Band to be 'the political guy': 'It occurred to me that I'd blown my life'

Steven Van Zandt just released his autobiography, Unrequited Infatuations, and Bruce Springsteen fans will no doubt enjoy reading all about Little Steven’s adventures with the Boss. But the book's most fascinating sections actually focus on Van Zandt's political adventures — like when he became a man on a mission to bring down South African apartheid, with his 1985 all-star benefit single “Sun City.” But Van Zandt confesses during his interview with Yahoo Entertainment that when he quit Springsteen's E Street Band to focus on activism, there were times when he believed he'd destroyed his career.

“I was on a flight to South Africa, actually,” Van Zandt says, recalling an especially intense moment of inner crisis. “My second [solo] record Voice of America had come out, and I was about to do the research for South Africa. I'd always been a very nervous flyer. ... And on the flight, a bit of a revelation hit me that I’d basically blown my life by walking away from the E Street Band, something that I've worked towards for 15 years. We’d finally had some success with TheRiver, the first thing I co-produced, and then Born in the USA, which I also co-produced — and I left before that tour. I’d spent my entire life in that direction, hoping to make a living playing rock ‘n’ roll, and finally I do it and I walk away from it. And it occurred to me that I’d blown my life.

“And so all my fear left me at that point, completely, suddenly. I go from sort of trembling on planes to not caring one bit about it — which helped when it came to the research of going into dangerous places, because I was literally fearless at that point,” Van Zandt continues. “You know: a ‘they want to kill me? Good, do me a favor!’ kind of an attitude. It's nice to get to that place, because it's very liberating. But I wasn't quite ready to commit suicide in the obvious way. … So, I thought, ‘Well, I'm committed to this political thing now. I'm really jumping in. I have to be a 100 percent committed to this, because this is all I've got left.’ That really helped focus your mind on what you're doing. And from that came the strategy to bring down the South African government, which I fully, fully intended to do.”

It was actually when Van Zandt — who admits in Unrequited Infatuations that he spent most his youth being entirely ignorant of current events or world affairs — was on The River European tour leg that he had his first political epiphany, the one that ultimately sent him on his path towards South Africa and away from Springsteen. “A kid asked me why we're putting missiles in his country in Germany,” he recalls, referring to Cruise and Pershing II missiles that were stationed in West Germany and other European countries in 1979, heightening tensions between Eastern and Western Europe. “Of course I thought, ‘What a ridiculous question!’ But the question never left my mind, for weeks. And then I realized, oh my God, something that had never occurred to me before: This guy, this kid from Germany, wasn't looking at me like a rock ‘n’ roll guy, or a factory worker, or a Republican or Democrat. He was looking at me as an American. And that was an epiphany to realize that if we are a democracy — which of course I found out later that we're not— but you know, if we're mostly a democracy, we have obligations and responsibilities as citizens. So, I thought, ‘Well, everybody needs an identity, and that'll be mine. I'll be the political guy for a while and see what happens. … So, I became an artist/journalist, and started to write about and go to places.”

Van Zandt made a list of all of the conflicts that the U.S. was involved in (he estimates there were about 44 during the Reagan Administration), but when he “couldn't find out much about South Africa,” he decided he “had to go down there” and became proactive, taking two chancy South African trips in 1984. “I interviewed everybody I could, and found out that [apartheid] was just really slavery and it needed to go,” he explains. “It wasn't going to be fixed.”

Van Zandt’s subsequent plan was to release the Artists United Against Apartheid benefit album and “Sun City” single, which protested the South African policy of apartheid and supported performers’ boycott of Sun City, a South African resort that catered to wealthy white tourists. It was an age of many high-profile musical charity efforts — Band Aid’s “Do They Know It’s Christmas,” USA for Africa’s “We Are the World,” Hear ‘N’ Aid, the global Live Aid concerts of 1985 — but Van Zandt’s project was still “a little bit risky for artists to get on” because, he notes, “We were crossing the line from social concern — you know, feeding people in Africa — to the political. Pointing the finger, naming names, saying, ‘This is what's wrong, this is how we fix it.’ And I mentioned Ronald Reagan's name in the song, which was quite controversial at the time. You know, in that particular era, the Reagan era, here's Ronald Reagan, everybody's ‘happy cowboy grandfather,’ extraordinarily popular. And meanwhile, he’s committing crimes all over the world, with our tax dollars.”

Among the 54 musicians Van Zandt recruited for Artists United Against Apartheid were Bob Dylan, Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed, Bono, George Clinton, Keith Richards, Hall & Oates, Herbie Hancock, Ringo Starr, Jimmy Cliff, Bonnie Raitt, Pete Townshend, Pat Benatar, Joey Ramone, and of course his buddy Bruce Springsteen — along with many rappers (Gil Scott-Heron, Run-D.M.C., Afrika Bambaataa, Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Melle Mel, the Fat Boys, DJ Kool Herc), at a time when hip-hop was still largely considered a passing fad by many people in the music business.

“That's one thing we wanted to make a point of doing; I felt very strongly about rapping those days. The industry didn't like it and was hoping it would just go away, and they were very surprised that I was putting Melle Mel on next to Miles Davis and David Ruffin and Jackson Browne,” says Van Zandt. “I thought, ‘Here comes rap music, and this is the first time in my lifetime that Black artists are expressing themselves openly and freely and consistently,’ and I thought this is really, really a healthy thing and we need to support it. So we put them on the record, against all advice… and, of course, we were right. They ended up adding to the street credibility of what we were doing.”

Unfortunately, few radio stations would play the record. “It was simply too Black for white radio, too white for Black radio — because we have our own apartheid right here in America, you know?” Van Zandt grumbles. But after Van Zandt and his cohorts made a visceral music video directed by Julien Temple and edited by Godley & Creme, MTV got on board. “I convinced MTV to play it at a time when they weren't playing many Black artists. You know, they didn't really want to,” says Van Zandt. “It was a big war about Michael Jackson… So, I convinced them and I said, ‘Look, if you play my video, you get to play more Black artists than you'll ever play in your life,’ because we had all kinds of Black artists on the record.

“So, it was really wonderful and it was completely successful. We ended up raising enough consciousness to override the Reagan veto, the economic sanctions bill, which was the key to freeing South Africa. Of course, Reagan vetoed it. And the first time his veto was overridden, which was a really extraordinary victory at the time. And then the banks cut off South Africa. They had to release Mandela — and goodbye, apartheid.”

One might assume that “Sun City” would have made Van Zandt a hot property in the music industry and helped boost his post-E Street career, proving that all those fears he had during that harrowing South African plane flight were unfounded. But he tells Yahoo Entertainment, “On the contrary — it was a real career risk to take part in this video. And in fact, at that point I was making a new record deal, and there were four deals on the table when ‘Sun City’ was a success. Those four deals disappeared. So, yeah, so it was the opposite of a career move. ... I think my guess would be that we were a little bit too effective and people started to get nervous around me. They started to get afraid of me and they figured, you know, ‘It's a popular government. What's next? Maybe we're next!’ I really had a big mouth in those days and I wasn't afraid to use it, so corporations were not that comfortable with me.”

Van Zandt officially rejoined Springsteen’s E Street Band in 1995 and went on to enjoy success with many other ventures, like The Sopranos, Lilyhammer, his SiriusXM channel Little Steven’s Underground Garage, his record label Wicked Cool, and his Rock and Roll Forever Foundation. But it seems like his logical next career step would be to go into politics himself. Van Zandt eschews the idea of running for office himself, but he does say he has another book in the works that will focus on that passion.

“I didn't want to put too much politics into [Unrequited Infatuations]. I wanted it to be really as universal as possible,” he explains. “But I actually have a book half-written, and it's been half-written for a long time, that really details all of my political thoughts. And I threw a few of them in that last [Unrequited Infatuations] chapter there, just to get conversations started. I have an entire book that is about that. We'll see if somebody wants to publish it or not.”

Check out Steven Van Zandt’s full, extended Yahoo Entertainment interview about Unrequited Infatuations below:

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

· Steven Van Zandt on why millennials are a 'more evolved species' and why he's putting politics aside

· Steven Van Zandt says 'Born in the USA' misunderstanding 'paid a lot of my bills'

·Why Butch Walker's 'love story about hate' might be the rock opera America needs right now

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Spotify