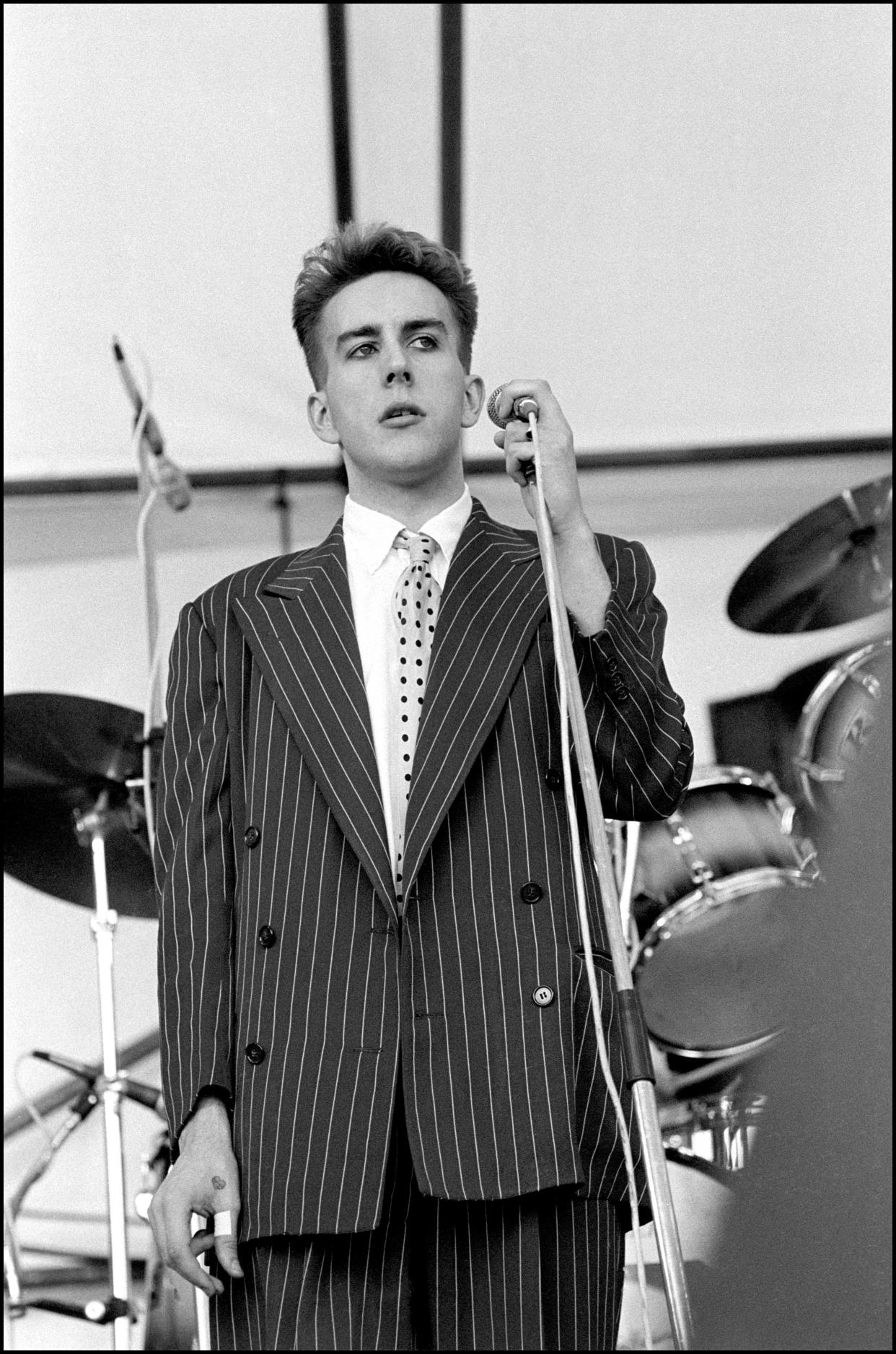

The Specials' ska and new wave pioneer Terry Hall dead at 63

Terry Hall, frontman for one of the most influential British new wave bands of the 1980s, the Specials, has died after a short, undisclosed illness, according to his bandmates. He was 63 years old. (Update: In a lengthy and emotional Facebook post, Hall's bandmate, Horace Panter, has revealed that Hall died of pancreatic cancer.)

“It is with great sadness that we announce the passing, following a brief illness, of Terry, our beautiful friend, brother and one of the most brilliant singers, songwriters and lyricists this country has ever produced,” the Specials tweeted Monday. “Terry was a wonderful husband and father and one of the kindest, funniest, and most genuine of souls. His music and his performances encapsulated the very essence of life… the joy, the pain, the humour, the fight for justice, but mostly the love. He will be deeply missed by all who knew and loved him and leaves behind the gift of his remarkable music and profound humanity. Terry often left the stage at the end of the Specials’ life-affirming shows with three words… ‘Love Love Love.’”

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing, following a brief illness, of Terry, our beautiful friend, brother and one of the most brilliant singers, songwriters and lyricists this country has ever produced. (1/4) pic.twitter.com/qJHsI1oTwp

— The Specials (@thespecials) December 19, 2022

Terence Edward Hall was born March 19, 1959, in Coventry, Warwickshire, England. At age 12, he was abducted by a pedophile ring and subjected to sexual abuse, which led to him battling depression and addiction throughout his life. He was diagnosed as manic depressive following a suicide attempt in 2004, but in a 2019 interview for comedian Richard Herring’s “Leicester Square Theatre” podcast, he matter-of-factly stated, “It’s unfortunate it happened to me, but you can’t just let it destroy your life.” Hall quit school at age 15 and soon became a fixture of the late-‘70s Coventry music scene, joining the Specials (originally called the Coventry Automatics) when he was 18 years old.

In 1979, after releasing their Elvis Costello-produced self-titled debut album on their own 2-Tone label and receiving support from the Clash’s Joe Strummer and BBC Radio 1 DJ John Peel, the Specials found themselves at the forefront of Britain’s ska revival — along with Madness, the Beat, and the Selecter. The group’s multiracial lineup (which included Neville Staple, Lynval Golding, Roddy Radiation, Horace Panter, Jerry Dammers, and John Bradbury); activism via organizations like Rock Against Racism; and sociopolitical messaging all resonated deeply with disfranchised British youth during the bleak and tension-filled Thatcher era. For instance, “Rat Race” was a scathing critique of privileged university students, while “Ghost Town,” which was released during the recession and amid race-related unemployment riots in Brixton and Liverpool, became the Specials’ signature song.

Looking back on the Specials’ formation during a 2019 interview with Yahoo Entertainment, Hall recalled, “We were all unemployed. In the area we lived in, Coventry, the manufacturing industries had all closed and there were absolutely no jobs. Growing up in the ‘60s, every kid went into the same profession as their father or mother and there were all open invitations to work, and then in the mid-‘70s, that stopped. It was a very, very gray place. And I think with the advent of punk, it said to kids, ‘There is something you can do. Not sure where it will lead, but why don’t you form a band, and why don’t you talk about how you feel?’ And we all did that, pretty much, after seeing the Pistols and the Clash.”

Hall also told Yahoo that he was surprised that so many people made a fuss over the Specials’ integrated lineup, saying, “We didn't find it a big deal, because when I grew up, I went to a school that was probably 70% West Indian and Asian. We all grew up in the same area and went to the same places. For me, one of the funniest first reviews we got was when the Guardian pointed out that we were a multiracial band, and it was like, ‘Yeah, of course we are. Um, here's our photo!’”

The Specials charted seven top 10 U.K. singles during their first run, and today The Specials is considered a landmark recording, appearing on Pitchfork’s list of the Best Albums of the 1970s and on NME’s list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. But by 1982, Hall had left the Specials to form the more pop-leaning Fun Boy Three with Staple and Golding. Fun Boy Three went on to rack up six top 20 singles in the U.K., one of which, “It Ain't What You Do (It's the Way That You Do It),” helped launched the career of girl group Bananarama. (Fun Boy Three later supplied their background vocals to Bananarama’s top five single, “Really Saying Something.”) Hall also cowrote the Go-Go’s’ first hit, “Our Lips Are Sealed,” with Jane Wiedlin, with whom he’d had a brief affair while the Go-Go's were on tour with the Specials in 1980. Fun Boy Three split in 1983 after the release of their second album, the David Byrne-produced Waiting.

Following the original Specials’ breakup, the remaining members recorded and toured under the monikers Special A.K.A. and Special Beat, while Hall busied himself with various musical projects and collaborations, including the Colourfield, the Lightning Seeds, Vegas (with Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart), and two solo albums. Over the course of his career, Hall also worked with Damon Albarn, Sinéad O'Connor, Dub Pistols, D12, Tricky, Junkie XL, Lily Allen, and Shakespears Sister, and Toots and the Maytals; the latter record, 2004’s True Love, won a Grammy for Best Reggae Album.

Inspired by the Pixies’ massively successful 2004 reunion, Hall eventually decided to reunite with his former Specials bandmates in 2008, and the group toured extensively. But it wasn’t until February 2019 that they released a new studio album, Encore, comprising the Specials’ first new material with Hall since 1981. The LP also included a spoken-word appearance by then-20-year-old “accidental activist” Saffiyah Khan, who had gone viral after a photograph circulated of Khan (wearing a Specials T-shirt) defending a Muslim woman against EDL members in Birmingham, England.

Encore was critically acclaimed and debuted at No. 1 on the U.K. Albums Chart, making it the highest-charting album of the Specials’ career. A compilation of covers, Protest Songs 1924–2012, followed and peaked at No. 2 in the U.K.; this turned out to be the final Specials album featuring Hall’s vocals. A reggae record by the band was reportedly in the works, but that project was put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the time of Encore’s release, Hall admitted to Yahoo Entertainment that the Specials' comeback album had “connected at a very unfortunate time,” and that he was experiencing déjà vu “every single day” as he witnessed what was going on with Brexit and Trump. “When we made the first Specials record, there was a woman prime minister — a Tory — and today, there is a woman prime minister Tory [Theresa May],” he said. “Back then, our closest allies across the ocean had an ex-film star [Ronald Reagan] who rode horses as their president. Today, your president... well, I have no idea. I can't even begin with that one. But it just feels exactly the same. ... It’s actually got a lot worse.”

Clearly, the Specials’ message still connected on both sides of the pond: Three months after Encore’s release, they were honored at their own “Specials Day” ceremony in Los Angeles, where councilwoman and obvious Specials fan Monica Rodriguez stated, “The late ‘70s was a time filled with racial tensions, but the Specials were made up of both Black and white performers, and their lyrics encouraged racial harmony while celebrating our many differences.”

Terry Hall is survived by his wife, director Lindy Heymann, and his three sons.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: