The Best Bob Dylan Documentaries

More from Spin:

Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Plant & Krauss Anchor ‘Outlaw’ Tour

Bob Dylan Stuns Farm Aid With Surprise Heartbreakers-Backed Set

The sheer number of documentaries about Bob Dylan suggests an unsolvable mystery, a massive event that demands interrogation. It’s a treatment otherwise reserved for the JFK assassination and World War II.

Dylan’s life is often seen in discreet, impactful events—going electric, his motorcycle accident, the country album, et al.—and tying them together is difficult when the subject resists being nailed down, as Dylan does. The deeper these films dive into his life, music, and legacy, the less clear he can become. Increased scrutiny will make most lives seem multifaceted, less of a single story and more a tangled ball of intersecting experiences. Dylan is that to the nth degree.

How do you even succinctly describe him? Musician? Certainly. But also, artist and activist. Poet. Cultural icon. Actor. More reverential and contemptuous terms have also been used. Prophet. Anarchist. Evangelist. Judas. These titles don’t leave much space for the human, father, husband, or friend.

Dylan’s shifting facades have fascinated fans for decades, and these movies attempt to find some form of truth about why he has so insistently captured our attention. Though “truth” is something Dylan—and some of the filmmakers—would surely laugh at. It’s as subjective as this list. With that in mind, let’s rank more than 50 years of documentaries about the, I don’t know, troubadour? Visionary? Charlatan? About Bob Dylan.

12. World Tour 1966: The Home Movies (2003)

It would be easy to dismiss World Tour 1966. It’s a documentary about Dylan without much Dylan in it. Despite his absence and the reality that his “going electric” moment has been well documented elsewhere (see below, repeatedly), there’s still a fresh perspective here.

World Tour 1966 centers on 8mm home movies shot by original Hawks (later dubbed “the Band”) drummer Mickey Jones, who talks at length about being part of Dylan’s first electric shows. Jones goes deep into being recruited by Dylan, the Band’s evolution, meeting the Beatles, and fan vitriol. There are also occasionally charming moments that feel like a relative describing their “vacation of a lifetime,” like when Jones talks about sightseeing between shows and seeing the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace.

11. Festival (1967)

Director Murray Lerner made more than a dozen music documentaries during his career, with subjects such as Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, and Miles Davis. Nonetheless, Festival might be his finest work. His ability to capture the spirit of a concert is on display as he shares four years of footage from the Newport Folk Festival, including performances and interviews with artists like Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Howlin’ Wolf, Son House, Johnny Cash, and, of course, Bob Dylan.

It’s a beautiful film, but Dylan isn’t its subject. He flits in and out of the picture, a fleeting but inextricable presence. However, the moments he is present are significant. The 1963-’66 time frame includes Dylan transitioning from acoustic to electric sets, accompanied by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. There are also less-than-enthusiastic responses from Newport attendees and one promoter so angry he wants to kill the stage’s power with an axe.

10. Renaldo & Clara (1978)

According to the Band’s Levon Helm, Dylan almost bailed on Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz in part because he had recently finished Renaldo and Clara. Dylan directed that four-hour film about his Rolling Thunder Revue tour, a sort of variety show featuring an entourage of familiar musicians, poetry readings, and other on-stage antics that often saw his musical menagerie adorned in costumes, facepaint, and masks.

Both critics and audiences were tough on the movie, and it’s not hard to see why. Renaldo and Clara is long and lacks focus. There’s concert footage, cinéma vérité-style passages, staged interviews, person-on-the-street interviews about Rubin “Hurricane” Carter’s wrongful imprisonment, and scripted vignettes that never coalesce into a single vision. Still, there are entertaining moments and glimpses into the director’s mind.

9. Hard Rain (1976)

Hard Rain is yet another documentary attempting to capture the kaleidoscopic magic of the Rolling Thunder Revue. This time, it’s more strictly a concert film. Rolling Thunder began in 1975 and, after a break, commenced a second stretch of shows in the spring of 1976, crossing the south and midwest. By many accounts, that spring didn’t carry the same cacophonous celebration as the tour’s earlier dates.

Hard Rain was shot during one rainy show in Fort Collins, Colorado, as personal problems were surfacing. Dylan doesn’t exhibit the same exuberance felt earlier in the tour, but that somewhat dour demeanor makes it compelling. Instead of shots from the audience, wide-angle embraces of the stage, or a broader sense of the day, viewers are repeatedly given tight shots of Dylan’s stoic face, creating a provocative intimacy, whether he’s alone or sharing the microphone with Joan Baez. Despite the raucous arrangements, there’s tension in stellar performances of “Shelter From the Storm” and “Idiot Wind.”

8. The Other Side of the Mirror: Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival (2007)

In 2007, Lerner revisited his Newport Folk Festival footage to create The Other Side of the Mirror. The film collects Dylan’s sets from 1963 to ‘65, effectively crafting a portrait of his evolution from Woody Guthrie-like folk superstar to the genre’s Benedict Arnold. It’s a delight to see Dylan move from leading an all-star collaboration of “Blowin’ in the Wind” one year to, in another, leading a plugged-in, almost psychedelic “Maggie’s Farm” that bursts from the festival speakers bearing its teeth. Of course, just as it provides a lens into Dylan’s evolution, you can also see the evolution of his fan reception.

7. Eat the Document (1972) and 65 Revisited (2007)

While these films are different, both are around an hour long, hard to find, and at least partially helmed by D.A. Pennebaker. 65 Revisited showcases unseen footage and performances from Pennebaker’s seminal Don’t Look Back, which documented Dylan’s 1965 tour of the U.K. It also presents an alternative version of the iconic video for “Subterranean Homesick Blues.”

Eat the Document, which credits Dylan as the director, occurs during a U.K. tour the following year and features the Free Trade Hall “Judas” incident as well as a brief limo ride with John Lennon. Cinematographer and editor Howard Alk called Pennebaker’s original cut “Don’t Look Back, Revised.” When Dylan recovered from his 1966 motorcycle accident, Alk and Dylan made their own edit. When it screened at the Whitney in 1972, Alk’s program notes said, “Instead of trying to re‐create the ‘real’ event, with a vérité documentary approach, the editors looked for what each shot itself wanted to be.” His notes reveal part of why Eat the Document feels unfocused and slight compared to Don’t Look Back.

6. Trouble No More — A Musical Film (2017)

Often derided and frequently dismissed, Dylan’s so-called Christian trilogy—Slow Train Coming, Saved, and Shot of Love—was given a spotlight for reassessment with the 2017 Bootleg Series release Trouble No More 1979–1981, which was accompanied by this documentary.

From the start, Trouble No More positions his evangelical turn as analogous to his early electric sets by including audio of fans disinterested in this new Dylan. It’s primarily footage from his gospel-infused 1980 tour, homing in on the music and forgoing his apocalyptic lectures. However, it does juxtapose performances with short scenes of actor Michael Shannon delivering fire-and-brimstone sermons in a dimly lit church. It feels as odd as it sounds—until it finds a rhythm and builds the sense that Dylan didn’t simply love gospel or religious music, but was rife with belief and passion.

5. Getting to Dylan (1986)

The BBC’s Omnibus followed Dylan’s series of weird ‘80s decisions to the set of the poorly received 1987 film Hearts of Fire, which starred Dylan alongside Rupert Everett and Fiona Flanagan. The title of the 50-minute episode alludes to a philosophical quest to find the soul of the artist. It also alludes to the crew’s uncertainty about getting to interview the mercurial star.

Fortunately, both missions succeeded to varying extents. Host Christopher Sykes interviews an adversarial Dylan, killing time between takes. “I’ve come through good times and bad times, you know,” he tells Sykes. “I’m not fooled by good times or bad times.” The musician-turned-actor offers non-answer after non-answer in an interview that shifts from playful jousting to clear-eyed confrontation and back again. “I’m trying to satisfy your need to probe into my private life and thoughts here in a way that’s not going to embarrass me,” Dylan says. It’s a brief but engrossing portrait of Dylan stepping out of his comfort zone in more ways than one.

4. I’m Not There (2007)

Todd Haynes’ Oscar-nominated I’m Not There isn’t a documentary, but its experimental approach cares less about linear narratives than unearthing something true about Dylan, fictionalized though he may be.

It features six actors playing Dylan or, perhaps more accurately, some small aspect of Dylan’s personality or career. However, none of them are named Bob Dylan. Marcus Carl Franklin plays a train-hopping boy who goes by Woody Guthrie. Ben Whishaw plays Arthur Rimbaud at a press conference. Cate Blanchett’s Jude is a thinly veiled Dylan circa ‘65, with recreations of moments from Don’t Look Back and Dylan’s Newport performances. Richard Gere is Billy the Kid, a reference to Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, in which Dylan appeared. (Kris Kristofferson, who played Billy the Kid for Peckinpah, narrates here.) I’m Not There is unequivocally fictional. Yet it recreates scenes first captured in documentaries, blurring the already hazy line between fiction and non-fiction in film. (Also, make a movie about Allen Ginsberg starring David Cross already.)

3. Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story (2019)

Given the variety of films discussed here, it’s surprising that the weirdest is, on the surface, a straightforward documentary directed by Scorsese. It spotlights previously unseen footage and performances—much of it from Renaldo and Clara—from the tour, including a ravishing rendition of “Isis” pre-Desire. It also features a new interview with a still-evasive Dylan. In an archival scene, Ginsberg says Dylan’s conception of the tour was to “show how beautiful he is, by showing how beautiful we are.” In those terms, Scorsese captures the tour’s playful, collaborative, anything-goes spirit.

“When someone’s wearing a mask, he’s gonna tell you the truth,” Dylan says at one point. It sounds like something Dylan would say, not a cue that something is amiss. The line evokes Orson Welles’ devilish promise in the documentary F for Fake: “During the next hour, everything you hear from us is really true,” he says in his familiar baritone, opening a 90-minute movie that contains 30 minutes of bullshit.

Likewise, a good chunk of Rolling Thunder Revue is a ruse. The Dutch filmmaker who speaks at length about filming the tour and his relationship with Dylan? He doesn’t exist. Sharon Stone’s tale of winding up backstage at 19? The fictional concert promoter? Former politician Jack Tanner? (Cue Jonathan Frakes) Pure fiction. At its best, these moves can be seen as an homage to Dylan’s tendency to wind people up. At its worst, it can feel Trumpian in its commitment to the bit.

2. No Direction Home (2005)

Created for PBS’ American Masters series, Scorsese’s three-and-a-half-hour artifact may be the definitive film on Dylan’s career. The director delves deep into his subject’s life and music, tracing his Minnesota roots to smokey Greenwich Village venues and his gasp-inducing foray into electric guitars.

Scorsese uses a good deal of Pennebaker’s footage as the glue between archival concerts and interviews with figures like Peter Yarrow, Seeger, and Baez. More importantly, No Direction Home features Dylan speaking on his career in the early ‘00s. Though, again, the interviews are conducted by Dylan’s manager and not Scorsese. Dylan is uncharacteristically open and, at least seemingly, honest, if still cagey as ever. While lengthy, the movie tries to do a lot, including showcasing moody solo acoustic performances and the bombastic energy of early shows with the Hawks.

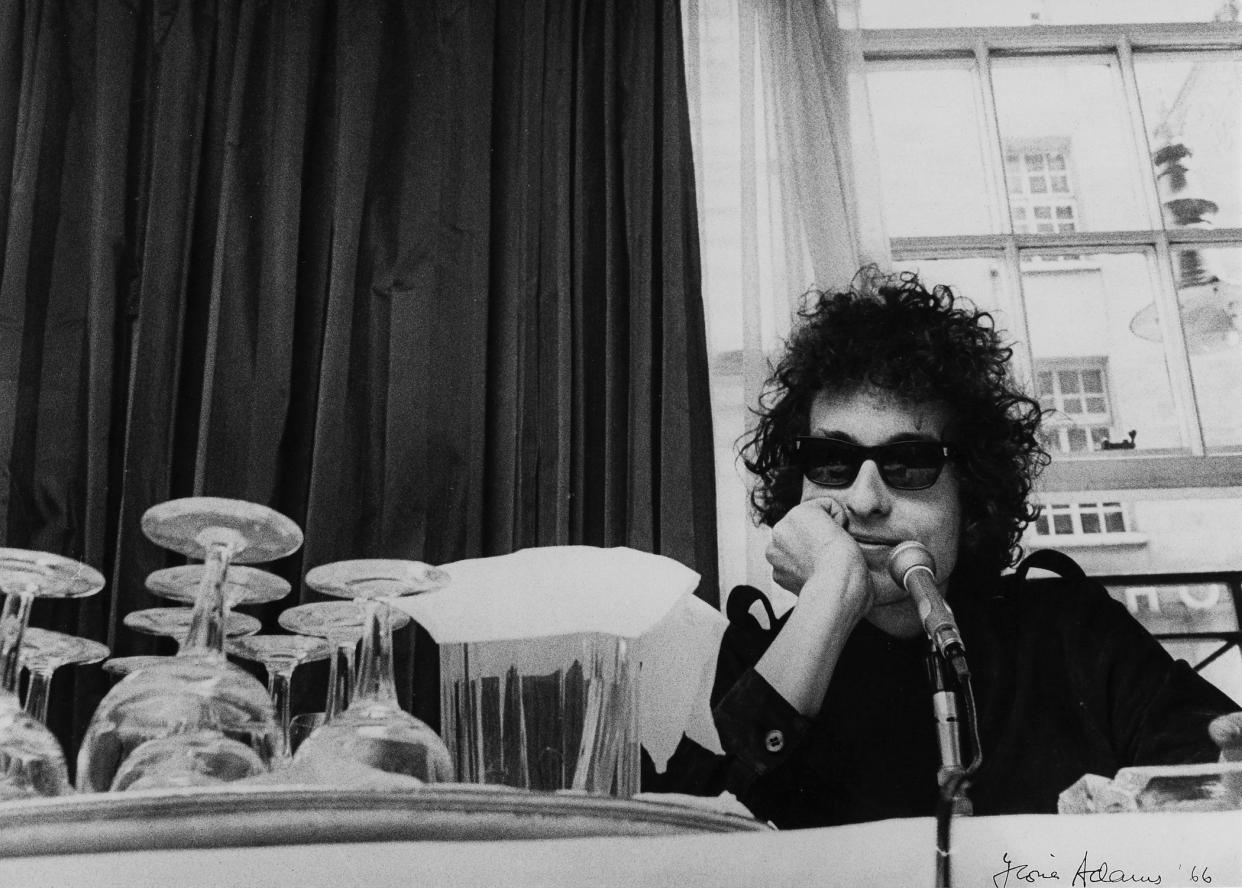

1. Don’t Look Back (1967)

Arguably Pennebaker’s greatest work, Don’t Look Back is a classic of cinéma verité, a style that tries to get at truth through a more naturalistic style of filmmaking. You won’t find interviews, talking heads, or an intrusive director. It offers a backseat ride to Dylan’s 1965 U.K. tour with concerts, rehearsals, a hotel room argument with Donovan, and iconic instances of Dylan toying with the press.

While it’s not loaded with information or insights from the people who were there, it’s as intimate a portrait of the artist as has ever been created. The gorgeous black-and-white film doesn’t serve up a fleet of facts about Dylan’s career or attempt to place him in a larger cultural context. Still, viewers emerge with a feeling of what it was like to be in Dylan’s orbit, a feeling of who he is in ways that other documentaries—even by Pennebaker himself—have never been able to duplicate. With a subject as thorny and elusive as Dylan, it’s a Herculean feat.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.