Emily Henry on the Wisdom of Modern Romance Novels: “Love Is Not Just a Silly Story”

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

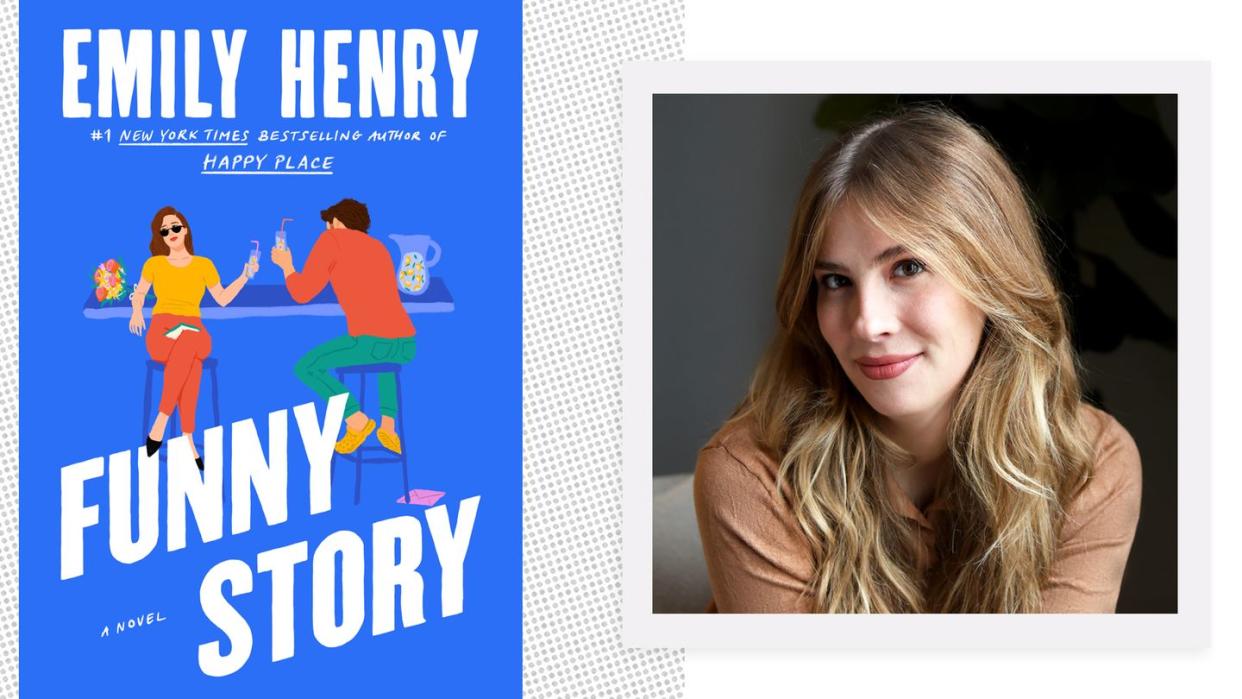

Emily Henry remembers a time, not so long ago, when publishing one book a year didn’t feel like enough. The novelist—beloved for her effervescent-but-poignant love stories including People We Meet on Vacation, Happy Place, and her latest, Funny Story—has maintained her steady steam of yearly romance releases since 2020, when Beach Read became her first official foray into the genre and claimed its space as a smash hit. Readers inhaled her witty banter and adored her emotionally available MMCs (“male main characters.”) As so-called “EmHen” books accumulated, fans debated the merits of Henry’s pairings: Were January and Augustus from Beach Read more likely to last for the long haul, or were Nora and Charlie from Book Lovers? Henry wrote more, faster, eager to challenge herself and keep these romance readers—a notoriously voracious category of the literary market—happy and fed.

But as film and TV rights of her books have sold, and the subsequent adaptation-adjacent work has piled up, the author’s realized the book-a-year model might not be sustainable forever. Three of her books, Beach Read, Book Lovers, and People We Meet on Vacation, are in the process of being adapted for film. Says Henry, her workload “will have to evolve one way or another, whether I take a step back from publicity stuff, or I take a year off and let ideas percolate and get other work done and come back.” She envisions a future where she publishes once every 18 months, or once every two years. She imagines stepping outside of the romance umbrella, as she did in her early writing career. But for the time being, she’s tap-dancing to keep up the pace she set for herself. “I’m going with it,” she says, breezy and unflappable.

Of course, that last part—Henry’s seemingly inexhaustible positivity—is but one explanation for the author’s appeal. Like the vibrant cartoon covers that adorn her novels, Henry’s good nature only overlays the deeper, more heart-rending qualities that make her work so accessible. In interviews and with her readers, she’s been transparent about her struggles with anxiety and existentialism. When she set out to write last year’s bestseller, Happy Place, she’d planned to publish a screwball comedy of remarriage. Instead, she wound up with a “sad, angsty book with a lot of jokes in it,” she says. “I could not find a way to not make it sad. I tried so hard, and the only way to not make it sad would be to really remove the characters from their emotions.”

Funny Story, in contrast, is certainly lighter fare: The book follows children’s librarian Daphne Vincent, who moves in with her ex-fiancé’s new fiancée’s ex, Miles Nowak, after she’s dumped months before her wedding. But even with such a transparently goofy premise, Henry ensures her characters are raw and real in their grief, their hang-ups just as painful as they are recognizable. After all, the author argues, “Breakups are horrible in the moment, and oftentimes later they’re very hilarious.”

Ahead, Henry takes ELLE.com deeper into her thoughts on romance tropes; her observations on whether the genre has become more “respected”; and her dispatches from the Hollywood trenches.

Funny Story by Emily Henry

bookshop.org

$26.97

Berkley BooksDo you have a list of romantic tropes you hope to try over the course of your writing career? Do you even think in terms of tropes when you’re coming up with ideas?

I feel like this conversation has become so prevalent lately, because BookTok has really identified all of the tropes. When people on BookTok are pitching the books they love, usually a part of that pitch is just listing tropes. I’d imagine there probably are some writers out there who are starting with tropes, but most of the writers I know and talk with regularly are like, “No, that’s reverse engineering in a way that would not work for me whatsoever.” Tropes, in a way, are sort of like genre—it’s ultimately meaningless. It gives you a starting point for, maybe, I’ll like this because I tend to like enemies to lovers, or, I’ll like this because I tend to like marriage of convenience, but the execution is still, always, what it comes down to.

I am not usually starting with a trope. The premises sometimes have a trope baked into them. So with Beach Read, I knew I wanted these two writers who were having this argument over literary fiction and “women’s fiction.” That, of course, feeds nicely into what we call “enemies to lovers.” But it was more the dynamic between those two specific characters that I was excited about. I am never intentionally putting [tropes] in. It’s usually happening because the characters have certain traits or certain behaviors, and eventually that fits into dynamics we’ve seen in the past.

Romance can get a bad rap because of the acknowledgement of tropes. But we are not the only genre with tropes. It always kind of cracks me up when someone is reviewing a romance novel and they’re like, “I had a great time, but it was predictable [because] of the Happily Ever After.” I don’t see people reviewing mysteries and being like, “This was so predictable. At the end we found out who the murderer was!”

How has your writing process evolved as the attention on you has grown? Maybe I’m projecting, but I can't imagine it doesn’t impact how you work.

Of course, yeah, it does. I’m sure there’s someone out there for whom it doesn’t. Godspeed to them.

[My readers] have given me the ability to do my dream job, and so I want them to be happy. We’ve developed a sort of rapport, where I know what they like. It’s what I like, for the most part, so we’re good. But then there’s the other side of it, where you want so badly to make those people happy—to give them what it is they’re excited about—that you can get into your own head and start doubting yourself.

I have to totally remove myself from social media. That has been a huge development, as far as my evolution as a writer: realizing, as much as I love engaging with my readers, that to be able to write without panicking, I have to step away and let the book be mine for a while. When I get into the later phases of editing, I do let [readers’] voices creep back up intentionally, because I want to make sure I’m creating something that we’re all happy with.

I think that having this large readership pushes me harder than I ever could have pushed myself beforehand. There will be people who don’t connect with every single book I write, and that’s okay, but I want to know that I pushed it as far as I could. I gave it my all, and I’m putting something out that someone out there is going to connect with so deeply that it will become their favorite book. That’s the goal for most writers. You want [your book] to be someone’s favorite book.

I truly do believe art is worth it, whether anyone ever sees it or not. The experience of making it is really significant, in the way that people used to practice alchemy and believe that it was changing them, maybe going to make them live forever. Art is sort of like that: It’s this magical thing that’s so good for the person who’s making it, and regardless of whether it’s ever shared with anyone, it matters and it has value. But when you devote at least a full year of your life to something, it is so affirming to have that one other person whom you’ve given this gift of an eight-hour reading experience that swept them away and stays with them. It validates everything.

Do you feel as though the overall perception of romance literature has shifted in recent years? Is the genre more respected, or is it simply that people are paying more attention because romance is making money in a way the market can’t ignore?

It’s interesting because, being so immersed in the romance world, I do feel like, yes, the perception has changed. There’s so many voracious romance readers. There are major publications covering romance. Romance is selling so well on the New York Times lists. It’s dominating them. All of that feels so true.

And then, sometimes, when I step outside of the little bubble of romance and see other people’s reactions, I am really jarred by how—I don’t know, backwards or prejudiced it is. Even moving from being in romance publishing to working on these [film] adaptations, I see how different the attitudes toward romance in publishing versus romance in Hollywood are. There’s still a huge stigma on romance in Hollywood. If you think about how stars tend to break out, it’s usually in either romance or horror, which are the two cheapest genres to make. They’re the least prestigious, arguably. And then once those two genres launch them hard and they’re beloved, then they go on and do other things. “You’re doing what we take seriously now. Maybe you could be up for an Oscar someday.”

The attitude there feels largely behind where publishing is. Publishing has realized, Oh, this is keeping our industry afloat. Let’s stop disrespecting our customers, our readers. Let’s try to understand what they love and why they love it.

When I interviewed [Beach Read film director Yulin Kuang] a few weeks ago, I asked her what about your work resonated with her. And she said it’s the parts of your books that are “on the bluer side of the human emotional spectrum.” Do you find those components—grief, doubt, trauma, loss—come to the story naturally as you’re plotting and writing, or are you intentionally carving out space for them in each book?

It comes totally naturally. The experience of actually falling in love—that’s not just a giddy, joyful experience. It is that, but it’s also often triggering. You find out if you have attachment issues; if you’ve been abandoned at any point; if you’re afraid that you’re not enough; if you’re afraid that you’re too much and you’ll drive someone off—all of those things come up when you let your guard down enough to fall in love. When you’re getting to know someone, you go through that phase where you are telling each other everything. You’re telling each other about your worst memories with your family when you were a kid, and your past relationships and the horrible things that happened. You excavate your histories together. It feels like you could not ever get enough because you love them; you want all of them. Falling in love is not just the warm happy feelings.

I have a really strong reasoning for why I write and read in this genre, and it goes back to what we were talking about with the perception of romance in general. A lot of people tend to think of romance as purely escapist: “It’s silly; it’s brain candy. So even if I approve of someone reading it, I don’t think that it’s got real merit.” Maybe there are writers out there who approach their books that way, and that’s great. But the thing that I love about writing love stories is that I think love is the thing that has the most power in the world to change a person.

Love is transformative. We go through so much hardship, and love—romantic or otherwise—is the grounding force that helps us keep going. If I stop and I step outside of my career, needing to pay the bills and all of that, and think about what do I want to do with my one wild and precious life? It’s love very well and be loved.

So I think those bluer emotions come out [in my work] because I genuinely believe that love is the flip side of grief. I think those two things are permanently cemented together. Anytime that you decide to love anyone, you are opening yourself up to unbearable pain. And we still do it over and over and over again. When we don’t, our life becomes flattened out. It’s less saturated. We have so much less joy. We’re trying to avoid the pain that comes with love. But every book I write is getting back to the point of, “No, the feeling of love is worth it.”

I have a very, very old dog. Doing all of these interviews, that’s the thing I keep thinking about: I’m bracing myself for saying goodbye to her. I’m thinking about how that pain is going to feel. I’ve felt it before. It’s the worst. But I wouldn’t un-know her to avoid feeling those things. That’s been such a beautiful relationship that’s meant so much to me for the last seven years.

Love is not just a silly story. It might be a funny story, but it’s not silly and superfluous. It’s the reason.

Has juggling the Hollywood side of your work transformed your perspective on publishing?

Well, it has given me a new appreciation for publishing. They’re such different industries. It’s shocking.

The thing that’s exciting to me about the [film] adaptations is that they’re collaborations. You get to work with a group of people, and they put their own voice and thumbprint on this thing, and it becomes something you could never make on your own. That is such a fun experience. But the other piece of that is, every decision is being made by a committee, especially within the big studio model. It’s very different from publishing, where it’s just me and my editor, so that when we’re making decisions, it’s one other person who I really understand and who really understands me and who knows what matters to me about my work. That has given me a new appreciation, too, for how much faster publishing moves: It’s just your voice and then, maybe, a couple of other people whom you’ve let in very close to you. Things have to move slowly if you have 20 people who have to sign on. And then hundreds of people who have to actually make the thing.

It is a challenge to go from publishing—where I feel like, with my team, I’ve proven myself; they trust me, and they trust my viewpoint—to then a totally new world where I feel like I’m there to be the representative of my readers. It is a miracle that any movie has ever gotten made, let alone a good movie. It gives me more understanding of how something can end up bad, because there are so many voices, and you’re working on something for so long; it’s easy to lose sight of it. You need a great team to keep something from falling apart.

Do you have any desire to write outside of romance again? Or does this genre feel like your literary home?

Love stories feel like my literary home. But I do think that I will, almost certainly, write outside of romance. I am relatively new to writing and reading romance. I deeply, deeply, deeply love the genre, respect it and appreciate it. But I also have always loved every genre. I assume that, at some point, I will be writing more widely. But I also am really trying to honor this moment and honor the readers. So it’s tricky because I have to stay true to my own self and what sounds the most exciting, but I am, again, trying to keep the readers in mind and keep them fed.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You Might Also Like