‘Dysfunction’: Teens’ grievances reveal safety, hygiene problems in KY juvenile justice facilities

Inmates got spoiled milk and uncooked or burned food, served with dirty cups and utensils.

Bed sheets weren’t washed for weeks. Inmates were threatened with sexual violence by other inmates.

Guards, who sometimes failed to conduct safety checks, withheld showers. Prescription medicines weren’t handed out.

Some days there was no running water in the cells, where inmates were stuck indefinitely and, in one case, was denied cleaning supplies after vomiting on the floor. Other days, the hot water heater, furnace or air conditioning were on the fritz.

“I don’t feel safe in this facility,” one inmate wrote.

These aren’t scenes from behind the walls of a maximum-security state prison.

Instead, they’re among the handwritten complaints submitted by teenagers in the custody of the Kentucky Department of Juvenile Justice from January 2023 through March 2024, according to a review of documents the Herald-Leader obtained through the Kentucky Open Records Act.

Each of these complaints — formally known as “grievances” — were determined to be legitimate after a review by department employees.

Overall, there were 87 substantiated grievances in that 15-month period at the four facilities examined by the newspaper — the juvenile detention centers in Adair, Campbell, Fayette and McCracken counties, which have experienced some of the department’s worst incidents in recent years, including riots, escapes and attacks.

But that’s just a sample.

The Department of Juvenile Justice operates 14 juvenile detention centers and youth development centers around the state. They hold hundreds of teenagers in an average year as they await legal action on criminal charges or serve their sentences.

The grievances provide a rare glimpse inside Kentucky’s juvenile justice facilities, which have been the subject of critical audits and multiple lawsuits alleging abuse, neglect and general mistreatment of youths.

The Herald-Leader analysis shows the most common grievances were related to poor sanitation, followed by safety concerns, staff misbehavior and bad or unclean food.

“Wow,” said Laura Landenwich, a Louisville lawyer whom the Herald-Leader asked to review the grievances.

Landenwich represents several juvenile inmates suing the department over their treatment in custody.

“These are consistent with what we have heard from our clients,” she said.

In her clients’ lawsuit, filed in January in U.S. District Court in Bowling Green, youths said they were attacked, humiliated and deprived of health care, education and basic hygiene while held in detention.

A 14-year-old boy said he suffered a broken jaw in an assault and had to wait four days until he was taken to a hospital for surgery.

Some of the suit’s allegations, like deprivation of showers and medicine, are similar to those contained in the grievances. Yet the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet is fighting her litigation in court while acknowledging the accuracy of the youths’ grievances behind closed doors, Landenwich said.

“The dysfunction in this organization is mind-blowing,” she said.

Officials say reforms underway

In a prepared statement, the Department of Juvenile Justice said reforms are underway to do a better job fixing the problems revealed by teens’ complaints.

“I am instituting a new process to the way facilities respond to substantiated youth grievances that will ensure consistency across each of our facilities and in our programs,” said newly appointed Juvenile Justice Commissioner Randy White, a former state prison warden.

White’s predecessor, Vicki Reed, resigned Jan. 1 amid widespread criticism of her job performance.

The department also will hire an additional ombudsman to monitor conditions inside its juvenile facilities and provide greater accountability, White said. The ombudsman is supposed to watchdog how youths are treated by the Department of Juvenile Justice, reporting to the commissioner.

“We encourage juveniles to file grievances and report to the Internal Investigations Branch so that Kentucky’s juvenile justice system can continue to make positive changes and create safe and secure environments,” White said.

How grievances work

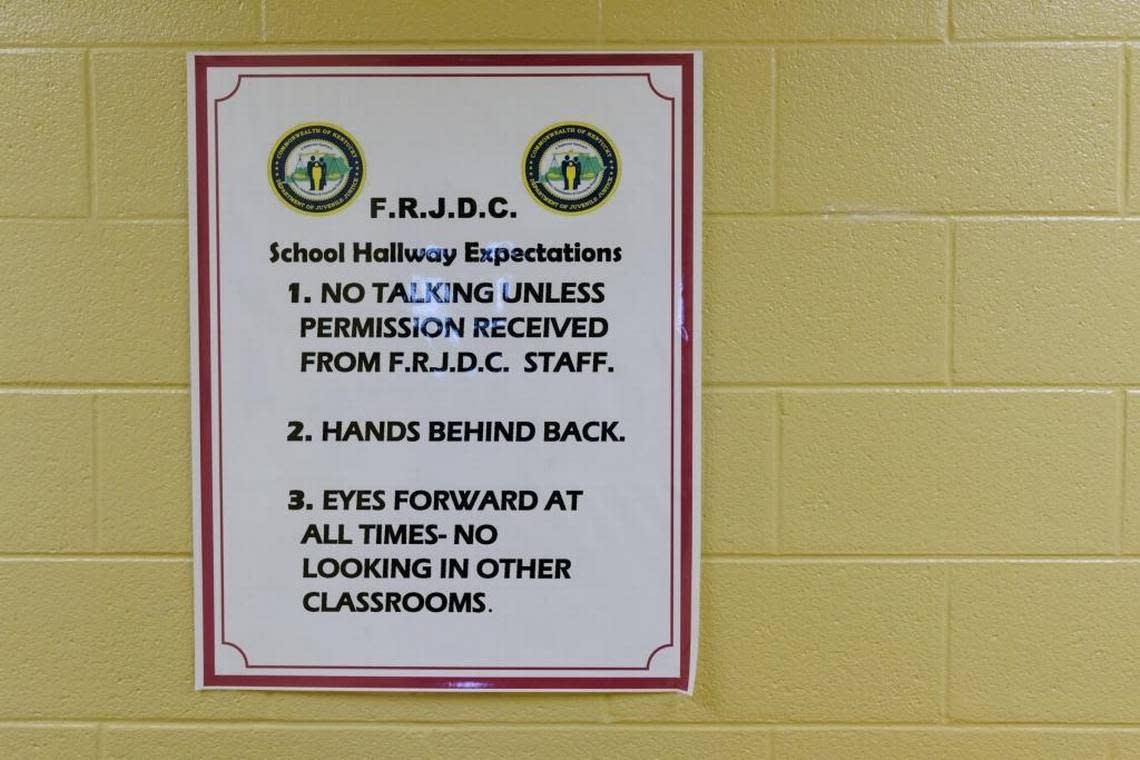

Under state policy, youths in custody with the Department of Juvenile Justice can file grievances alleging mistreatment, including violations of their civil rights.

Designated employees at each facility are named “grievance officer.” They have three days to read complaints and decide if they raise valid concerns and are accurate based on evidence, such as interviews and a review of security video footage.

Once they substantiate a complaint, grievance officers are supposed to decide how to resolve it.

For example, complaints about hair in the food at the Adair County juvenile detention center were met with a guarantee that youths could get a second meal tray if the first one was contaminated — and a reminder to kitchen employees to wear hair nets.

Girls at the Campbell County facility complained that staff wouldn’t let them put “privacy magnets” in the windows of their cell doors in order to temporarily hide their bodies when they used the toilet. The facility said staff would be addressed on this. Also, it said, the magnets gradually are being replaced with window tinting.

Youths were separated from each other after threats of sexual violence were reported. Staff were spoken to after grievances revealed that mandatory safety checks and prescription medicine distribution were skipped during their shifts.

A supervisor was informed after a complaint revealed that an employee called a boy “retarded.”

Cutting off running water in cells as a form of punishment, as one youth reported at the Fayette County juvenile detention center, is not appropriate, state officials said. That youth also said he vomited in his cell and was denied cleaning supplies necessary to mop up the mess, a claim the grievance officer substantiated.

Few employees, aging buildings

Grievance officers explained that some complaints — such as youths not getting showers, sometimes for days, or the opportunity to call their attorneys or caseworkers — were due to inadequate staffing, a long-standing problem at the department.

“It’s been busy,” one employee replied to a grievance at the McCracken County facility, where a teenager said he hadn’t been allowed to call his attorney for more than a week. “I ... will do better in getting these requests filled and done when I can.”

Other problems were blamed on broken equipment and aging buildings, such as phones and security radios that didn’t function properly, no hot water in the showers for extended periods and unreliable HVAC systems that failed to adequately deliver heat in winter or air conditioning in summer.

Most of the state’s current juvenile detention centers opened between 20 to 25 years ago.

During this year’s legislative session, the Department of Juvenile Justice wanted to get $165 million from state Sen. Danny Carroll’s Senate Bill 242 for a variety of needs, including building retrofits and long-overdue maintenance. But the bill died in the House.

Instead, a fraction of the hoped-for sum was provided in the state budget.

Given less money, the department has studied the physical needs of its detention centers to decide how they should be prioritized, said Morgan Hall, spokeswoman for the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet.

“More funding will be required in the next biennium to fully address all backlogged maintenance issues,” Hall said.

A grim picture

The grievances paint a grim picture of life in state custody for Kentuckians too young to even vote, said Rebecca Ballard DiLoreto, a longtime Kentucky children’s advocacy attorney.

DiLoreto helped bring a lawsuit that forced the state to establish the Department of Juvenile Justice in the 1990s, because the existing hodgepodge of juvenile lockups, overseen at that time by the Cabinet for Human Resources, was determined to be so bad that it violated youths’ civil rights.

“Based on the grievances filed by the youth in the DJJ facilities, I think Kentucky is back where we were in 1994,” DiLoreto said.

“It is important to remember that most of these children never had the level of due process rights that adults receive before they are incarcerated,” she said. “They are not entitled to bond or bond conditions while their cases remain in juvenile court. They are not entitled to jury trials.”

She added: “The juvenile system asserts to do everything based on the best interest of the children and public safety. But these conditions violate a child’s best interests and do nothing to promote public safety.”