Duped by DeSantis in Texas, he came to Florida for Ian cleanup — but was foiled again

Pedro Escalona endured a grueling journey from Venezuela to Texas, made a brief stopover at a San Antonio migrant center, crossed paths with an operative of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis — one who promised a free charter flight to Delaware — then learned the flight had been scuttled and caught a plane to New York City, where he ended up in a homeless shelter.

And now, days later, he sat forlornly on a bench in Doral, Florida, outside a Best Western, contemplating life’s odd twists. The company he had been working for had fired him, kicking him and three others out of the hotel room they had been staying in for a week. He had spent the night before on the grass of the hotel under a palm tree.

Escalona, 24, was angry and mostly broke, save for a check he could not cash — the fruits of an exhausting week of labor on a hurricane-recovery work crew.

“I feel like I’m nobody ... treated like an animal ... horrible,” he said last week Monday.

How he got to Florida — the state that wanted to dump him and others in Delaware, apparently to embarrass President Joe Biden, who has a home there — and onto a seven-day-a-week Fort Myers work crew is the story of America’s conflicted relationship with migrant workers.

One week they are demonized, the next they are in demand, only to become an expendable part of a workforce hired by companies that profit off vulnerable laborers.

The company had promised him three months of work, Escalona said, only to pull the plug after one week for something that, to Escalona, felt arbitrary and personal.

Read more: Perla was his boss. He was her ace. Inside the covert op behind DeSantis’ migrant flights

When the company fired Escalona, they painted him and his group as troublemakers. There had been some incidents, Escalona admitted. Some drinking and one fight, he said. But he insisted he and his friends did nothing worse than any of the other laborers in the group.

Although the company called the dispute with Escalona an isolated incident, the Herald spoke to five other migrants in the week since who described similar situations: hard work and long hours on hurricane clean up, followed by allegations of bad behavior, a final paycheck that they couldn’t cash, then abrupt removal from the hotel — sometimes at the hands of police.

There is no human relations department to arbitrate work disputes for an undocumented labor force. Escalona and the others found themselves in a position of trying to prove their own innocence, and enforce their rights as workers, within a company operating in a legal gray-area, unbridled by rules or regulations.

Escalona and the others can be easily replaced. An unprecedented number of Venezuelan migrants have crossed the U.S. southern border with Mexico this year, looking for an opportunity for work. But the process of obtaining a work permit takes months, limiting their options to under-the-table jobs.

When Hurricane Ian ravaged Southwest Florida, ruining a vast array of homes, it created an immediate, dire demand for physical labor. At a time when most stores and restaurants display help-wanted signs, one place to find muscle is at homeless shelters across the country, filling up with migrants spurned by government officials in states like Texas and Florida.

Two other people who were recruited for DeSantis’ migrant relocation program — a program that would have routed them from Texas to states other than Florida — told the Herald they are now headed to the Sunshine State for hurricane cleanup.

Escalona was staying at a New York City homeless shelter when friends gave Escalona the contact for a woman named Tatiana, saying she was looking to assemble a crew.

He reached out via text and was told a bus would be leaving for out of town at 7 p.m. — in less than two hours — and that the pay would be $15 an hour, $22.50 for overtime, $15 “daily for food” and that they would be put up in hotel rooms, each housing four workers.

Although Escalona had been tipped off by his friend that the job entailed going to Florida, Tatiana didn’t say where they were going or identity the employer. But Escalona heard from his friend that they would be cleaning up homes in a gated community damaged by Ian.

All he had to do was send Tatiana his name and show up to a bank location in Jackson Heights, a neighborhood in Queens.

After the bus ride south, Escalona and the other workers were checked into the Best Western in Doral and ferried back and forth each day to Fort Myers with other workers, before being abruptly cut loose after seven straight days.

The severance check, for $2,108, reflected the hours worked over seven days and an additional week’s base pay.

The company did not tell him that he would not be able to cash the check without an official ID — which Escalona didn’t have because it was taken from him by U.S. border officials when he entered the country. The papers he was issued in place of his ID can be used to board a flight but not at any of the check-cashing locations in South Florida that he or others could find.

And so, cashless, he sat outside of the Best Western, where he no longer had a room, trying to figure out what to do next.

From Venezuela to Fort Myers

After Escalona crossed the border into Texas and surrendered to authorities last month, he was granted parole, a condition that under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) allows migrants to come into the country temporarily for urgent humanitarian reasons.

The flight to New York City was arranged by Catholic Charities, which runs the San Antonio migrant resource center.

Parolees like him can apply for a work permit immediately upon entry into the country, but it takes months to be processed. By then, the migrants’ parole has often expired, leaving them unable to work legally.

To survive, many do find work — for employers that turn a blind eye. It is a system largely seen as broken, but with few easy answers.

“I understand that it’s illegal to hire them,” said Matthew Carr, the owner of Oceanside Labor & Demolition, the Plantation-based company that hired Escalona.

But Carr insists that he’s helping people — and that the law doesn’t reflect the reality on the ground.

“Everybody that crosses the border has to eat,” Carr said. “We live in Miami. There are so many people coming over here and trying to make a life. I’m trying to help people. Their life sucks in Venezuela and they can’t survive.”

Carr said he has a “couple hundred” employees working on Hurricane Ian cleanup. He said hiring workers who don’t have papers is a common practice in his industry, but that he tries to avoid it.

“I’m sure there are people that try to take advantage of them,” Carr said. “That’s not me. I pay them the same as someone with a Social [Security number].”

After their first brief exchange, Tatiana, the labor recruiter who never gave her last name, added Escalona to a WhatsApp group chat with more than 130 other people, all heading to Florida for work. Carr said he did not know how Escalona was recruited, but the WhatsApp group that Escalona joined was administered by someone with a Broward County phone number associated with Oceanside.

The migrant workers arrived on a bus from New York late at night and were told they had to be up the next day at 4 a.m. to file into another van and be driven to Fort Myers.

“They didn’t even give us more than a few hours of rest,” said one 30-year-old Venezuelan who did not want to share his name but was on the journey with Escalona.

The hotel offered free breakfast, but they were on the road before the spread was laid out.

Escalona was grateful that the gated community provided lunch and snacks. That was often the only meal he had in the day.

Every day, from 7:30 a.m. to after 5 p.m. the group of several dozen migrants — mostly young men — worked at the Bay Breeze Villas, a gated community of one- to three-bedroom rental apartments.

A public relations representative for Northland, a private equity firm in Massachusetts that owns Bay Breezes Villas, said it had secured the services of a local branch of Servpro, the disaster cleanup giant, which then hired Oceanside as a subcontractor.

Photos from the site show the workers in Escalona’s crew wearing Servpro vests.

Servpro issued the following statement: “Servpro Industries was not involved in the provision of these services and to report otherwise would be false.”

“All local Servpro franchises are independently owned and operated — and Servpro Industries as a franchisor does not provide or contract to provide any direct services to customers.”

A pay stub from one of the migrants showed the local branch as Servpro of Oldsmar/Westchase, which did not respond to a request for comment. It is unclear whether other branches were also involved.

Disaster recovery’s ‘dirty secret’

Hundreds of migrant workers are believed to be streaming down to Florida following Hurricane Ian.

Many of them are part of a mobile workforce, some with expertise in rebuilding communities after natural disasters, others simply muscle. They supplement an existing immigrant day labor force that can be seen huddling in parking lots of Walmarts and Home Depots waiting for work.

After Hurricane Michael devastated communities in the Florida Panhandle in 2018, hundreds of migrants descended on the region to help rebuild buildings, churches and campuses.

The fact that migrants like Escalona have always helped rebuild American cities following disasters is the “dirty secret” of disaster recovery, said Saket Soni, the executive director of an organization called Resilience Force that advocates for better working conditions for migrant disaster workers.

The current volatile political climate — where the “Biden border crisis” is a political talking point and the Texas border, in fact, sees mass daily crossings — is not lost on the migrant workers making their way to Florida, Soni said in an interview with the Herald/Times.

“These workers are very, very aware that they’re entering a harsh environment but they are necessary to the building. They’re deeply committed to rebuilding,” he said.

In June, DeSantis requested — and the state Supreme Court backed — having a grand jury look at immigration violations in Florida. Although largely focused on the influx of unaccompanied minors, the grand jury was also empowered to issue subpoenas relating to other areas, including people bringing migrants to Florida to work

In Ian’s aftermath, DeSantis urged cleanup companies to hire locals.

“Many Floridians in Southwest Florida have had their businesses and livelihoods impacted by the storm and are looking for work — the private sector can help them get back on their feet by hiring locally,” he said in an Oct. 7 news release.

DeSantis also used a hurricane-related press conference to single out three of the now at least 28 people charged with looting in hurricane-damaged areas and point out that they were undocumented.

“These are people that are foreigners. They are illegally in our country — and not only that — they try to loot and ransack in the aftermath of a natural disaster,” he said at the press conference in Fort Myers. “They should be prosecuted, but they need to be sent back to their home country.”

DeSantis’ hard-line immigration stance has always faced quiet push-back from the agriculture, tourism and construction industries, which rely on migrants to fill jobs. And the unmet need for labor is a harsh reality for those leading the recovery effort after Ian.

At a round-table discussion with local business leaders and the governor in Cape Coral, Matt Sinclair, president of Sinclair Custom Homes, warned that a lack of workers may be a hurdle to restoring their communities.

“The construction industry has experienced a shortage of labor and construction materials,” Sinclair said, making it difficult to “get displaced homeowners back in their homes.”

“The delays not only cost us money, but also waste precious time, as we’re ready, willing and able to begin the rebuilding process,’‘ he said.

The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Expendable labor

Escalona was part of a group of migrants that Oceanside fired late at night on Saturday Oct. 8.

The reasons given by Oceanside employees for his dismissal were vague and often included “rumors” that Oceanside said it couldn’t prove. But everyone agreed on a few points.

He and his friends had gotten drunk in the van on the four-hour ride back to Doral from Fort Myers earlier that evening, Escalona said. And he admits that there had been a disagreement with another migrant worker the previous night — during which he had a small pocket knife in his hand along with his cell phone and other personal effects from his pocket. The knife was never open, he said.

He didn’t think the drinking or the fight was the real reason he was fired. Escalona said he felt one of the company’s managers had it in for him. Both Oceanside managers at the hotel who spoke to the Herald but refused to be identified said the Venezuelan migrants hired recently have caused more problems than those in the past.

Shortly after the men returned to the hotel Saturday, two Doral police cruisers showed up — summoned by an Oceanside official who planned to fire the workers and feared trouble. Officers checked Escalona for weapons, and finding none, stood by as the men were fired.

A video taken by Escalona shows the men were advised they could stay overnight at the hotel, then had to clear out. They would be paid by check Sunday morning.

Carr said paying by check is an Oceanside policy. And texts show Escalona had been warned that he would be paid by check, not cash.

The men spent Sunday, without luck trying to find a business that would cash their check. They returned to the hotel and refused to leave the grounds until they got help converting their checks to cash. Reporters witnessed Oceanside employees assisting other managers with the check cashing process.

Escalona and the others spent Sunday night sleeping outside the hotel.

Although Oceanside insisted the incident with Escalona was isolated, and the result of a few bad apples rather than a bad system, the Herald has heard from at least five other Venezuelan migrants working in Florida who had similar problems with Oceanside since last week.

Three migrants said they were stuck in Tampa after they were fired by Oceanside and told they had to leave the hotel under threat of police. Unable to cash their checks and with few options, the group told the Herald they were considering walking to Miami to speak with the company.

“They want to do whatever they want to us,” said Yohander Perez.

Two others in Fort Lauderdale were fired Thursday and told they would have to wait until Monday for their checks. With nowhere to go and no money, one refused to leave the hotel room provided by the company. The company called the police and he was forced to leave.

Both groups were paid for one week of work on Monday and were told they could pick up another check for the remainder owed on the following Friday.

“They fire us and kick us out like we’re dogs and expect us to be thankful,” said Carlos Ortega, one of the Venezuelan migrants in Fort Lauderdale.

One problem solved, more to go

With nowhere to go and no money to move around, Escalona and his friends remained outside the Doral Best Western all day last week Monday, ignoring threats from Oceanside employees to call the police.

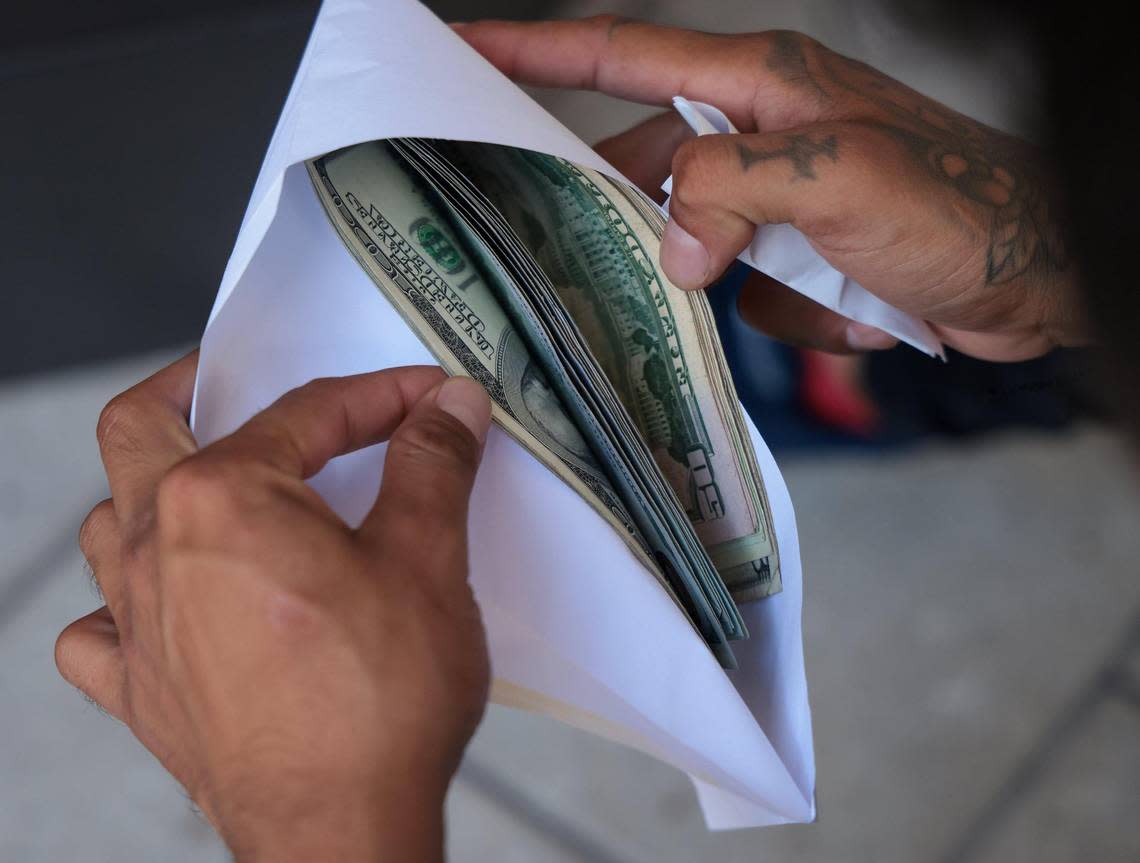

After a day-long standoff, documented by Herald reporters at the scene, the migrants were told by an Oceanside employee around 11 p.m. Monday that they could stay in the hotel that night, courtesy of the company. Late the next day, the same Oceanside employee returned to the hotel with four envelopes for the group.

Oceanside replaced their paychecks with cash, resolving the stalemate.

The group of four planned to return to New York, somehow try to acquire valid IDs and then find another job, with the hope of a brighter future.

“I’m going to be someone in this world,” Escalona said, “with the help of God.”

But the same had not been done for the other groups in Tampa and Fort Lauderdale earlier this week.

“At this point I won’t play this game of helping so that you don’t write a negative story about a problem that doesn’t exist,” a migrant recruiter said on Monday. “We never leave people without their pay, but things have their structure and norms.”

Carr, the owner of Oceanside, told the Herald on Tuesday that he was unaware of the latest issues with migrants being unable to cash their checks. He told a reporter to share his cell phone number with them so he could try to resolve the situation.

After speaking to the migrants directly, Carr arranged an Uber ride for the migrants from Tampa to South Florida so they could exchange their checks for cash.

Miami Herald staff writers Mary Ellen Klas and Charles Rabin and Tampa Bay Times staff writer Emily Mahoney contributed to this story.