For Drake Maye, the youngest in UNC’s unofficial First Family, the time is now

The story about the 36 scrambled eggs is as good of a place as any to begin to understand what it was like to grow up the youngest of the Maye Men, always fighting in one way or another to earn a place at the table. To prove the desire and the hunger, whether in a literal or metaphorical sense.

It’s as good of a place as any to begin to understand what it was like to be the youngest of four brothers. To be Drake Maye: the latest and greatest hope of North Carolina football; emergent Heisman Trophy contender; potential top pick in the NFL Draft; magazine coverboy; burgeoning commercial pitchman; perhaps the best college quarterback in America. But also: the baby of the First Family of UNC athletics. The little brother, and therefore perhaps the most tested.

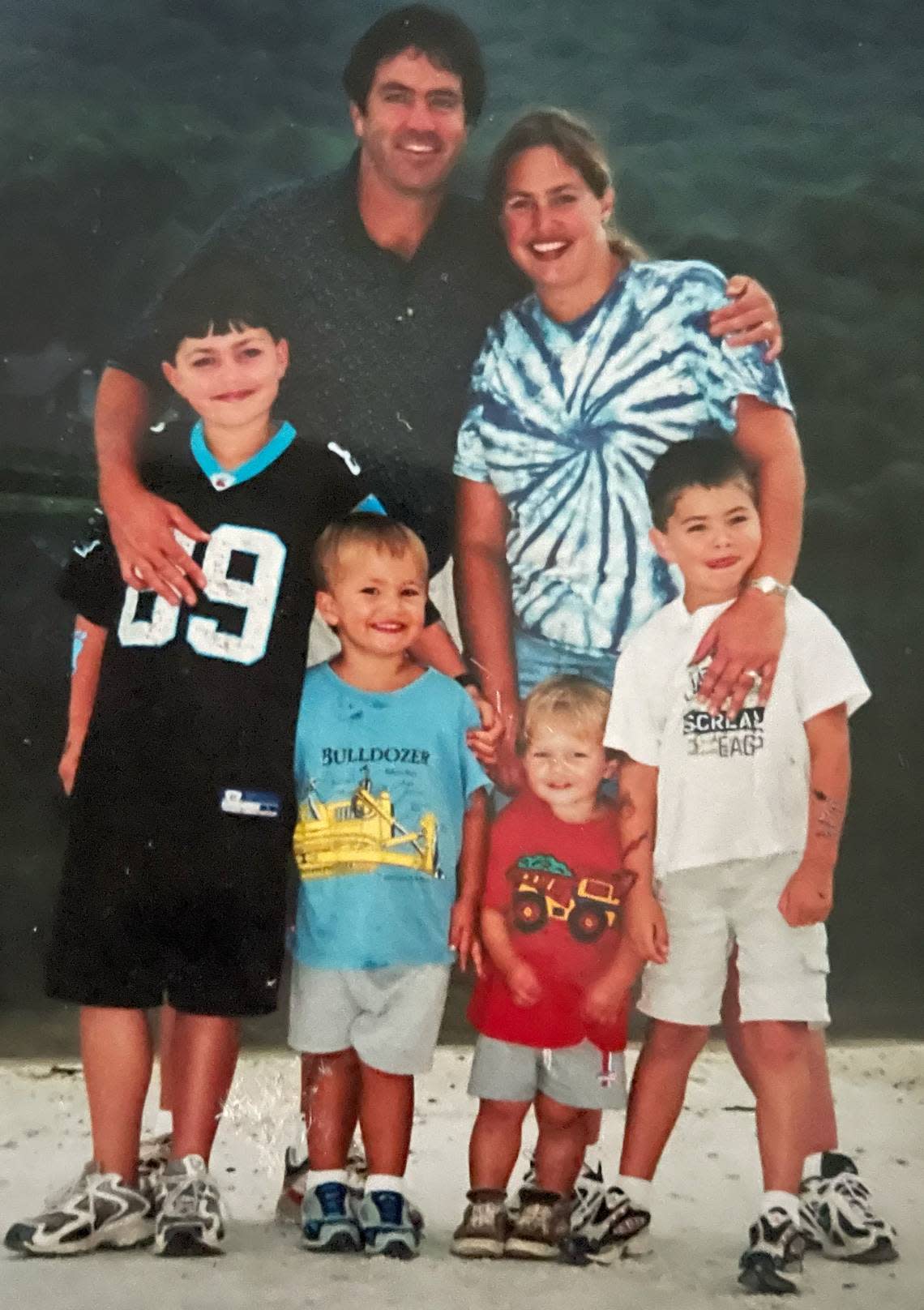

Among the proving grounds were the backyard football games in the cul-de-sac outside of Charlotte, Drake so small, his oldest brother Luke said recently, that “everyone was joking on him that he wasn’t really part of the fam.” And family games of H-O-R-S-E, where Aimee Maye, a standout high school basketball player herself and the most overlooked of the Maye athletes, asserted dominance over her sons until they learned to make their 3s.

Among the proving grounds was the classroom, where if Luke never made a B his brothers couldn’t, either. And then home, including the dinner table and the most gigantic pile of scrambled eggs anyone ever saw.

“Every time I tell that story,” Luke said, “everybody’s like, ‘What? Are you serious?’”

He once put his mom on speakerphone to confirm it in front of his basketball teammates at UNC. Enough years have gone by now that sometimes the number grows in the re-tellings: was it 36 eggs, or 30? Sometimes the circumstances are made to sound more dramatic, “like the tale of a fish,” Aimee said.

She knows two things for sure. One: “Of all the stories that’ve come out” about her husband, Mark, and their four boys, “I swear that is by far the most popular.” And two: sometimes the easiest way to feed everybody was to empty three cartons of eggs into what she described as “my huge skillet.”

The menu included sausage and bacon, about three or four packs, but the star of the meal was the eggs, piled all high and fluffy. And like just about anything else in the Maye house, it became a competition as to who could eat the most. The field was formidable, full of contenders who’d proven their mettle when the time was theirs.

No one ever doubted Mark Maye’s appetite. He remains one of the most accomplished high school football players to ever come out of Charlotte; people of a certain age still remember his recruitment and what a big deal it was when he chose to stay home and play at North Carolina. Luke, the tallest of his brothers, made the shot of all shots in Memphis in 2017 to send the Tar Heels to the Final Four, and toward another national championship.

Cole Maye, the second-oldest brother, was part of a national championship baseball team at Florida in 2017. Beau Maye, according to his dad and brothers, was as strong of an athlete as any of them before injuries affected his knees. And then Drake. The youngest. The one who learned early the value of competition; that “he had to get better quick,” as Luke put it recently.

Or “he was going to be last to get picked” in those neighborhood games, “or always get beat up on.”

As for the eggs, Cole insisted he could put away the most.

“I don’t know how true that is,” Luke said, offering that the winner was often Beau.

Sometimes it was hard to tell, Aimee said. All of her boys could eat at least six each. Usually more.

“I know for a fact every single time I made that meal, at the end of the meal, there was not a morsel of food left,” she said. “And some of the boys would be like, ‘I’m still hungry.’

“And I’m like, ‘too bad.’”

In the Maye house, all ate well. Yet there was a contagious kind of hunger, too, an appetite that extended well beyond mealtime. In school, in athletics — in anything, really — there was a competition, a quest for achievement.

“It’s just kind of how our family is; we always expect the best, and perfection,” Luke said, and now as the college football season begins a lot of eyes will turn toward his youngest brother, watching to see how he lives up to the ideal and everything that comes with it.

Drake Maye’s calm confidence

On a Thursday in late July, Drake Maye arrived in the Charlotte Westin in a pair of clean white sneakers, a trim navy suit, a white shirt and a Carolina blue tie whose knot hung a little lower around his collar than it should’ve. He wore a tan from the last family beach trip of the summer and he looked good, well-dressed, but also just a tad like he was putting on grown-up clothes for one of the first times; like he was still right in the thick of the transition from boy to man.

In reality, at 20 years old (he turned 21 this week), Maye had already become the public face of UNC football and one of the main attractions at the ACC’s annual preseason kickoff event. A horde of media crowded around his table, asking about everything from the hype to how he evaluates name, image and likeness deals to the disappointing finish to last season, which ended with four consecutive defeats after Maye had briefly become a Heisman contender.

Just about everything came easily for Maye on the field last season, or at least for long stretches of it. He earned every major conference award he could have earned (ACC Player, Offensive Player, Rookie and Offensive Rookie of the Year), and became the second to do that, behind Florida State’s Jameis Winston in 2013. Maye set the single-season school record for passing yards (4,321), tied it in passing touchdowns (38) and did things that put him in statistical company with the likes of Kyler Murray, Lamar Jackson, Winston and Johnny Manziel, recent Heisman winners all.

And then after Maye finished what was arguably the best individual season in school history he spent large chunks of the past eight months ruminating over the four losses at the end of it, re-watching them to study what he could’ve done better. By his count, he should’ve thrown for 500 more yards. He should’ve done a better job avoiding hits. At times he should’ve been more cautious. Someone at his table last month asked him about all the good things he did — the things he’d like to keep doing — and a few seconds later Maye was back at it with the self-criticism.

“Another thing I’m looking at to do better ...”

The Maye brothers have been the beneficiaries of many blessings, not the least of which are the enviable genes they share, the proclivity to succeed in just about any endeavor they pursue. If there’s a curse it’s perhaps that no one in the family came wired with an easily-turned off switch, not that Mark or Aimee or any of the boys would want to use one, anyway.

“You take two people who grew up in very competitive families, athletic backgrounds, talk about sports a lot, watch sports a lot, play sports a lot,” Aimee said. “And you marry them, and then they have four boys? It’s almost like a pressure cooker.”

And yet on the surface, an unusual calm. Mark exhibited it 40 years ago, when he became one of the most coveted high school football prospects in the country, all the while maintaining the grades that allowed him to become a Morehead Scholar at UNC.

Luke exhibited it in the final seconds in Memphis in 2017, when he made a shot that in school history ranks only behind Michael Jordan’s against Georgetown in 1982. Drake exhibited it throughout last season and again in Charlotte last month, cool amid the unrelenting media frenzy, looking calm as ever during a nationally-televised hit on SportsCenter.

After Drake referenced NIL during the interview, the anchor cracked a joke, asking Drake if the “slick suit” he was wearing was a product of endorsement money.

“I don’t know about that,” Drake said, containing a laugh. “I wear this to just about every event I go to. I’ve only got one of ‘em.”

The Maye boys inherited self-deprecating humility from their father, who never accomplished anything he couldn’t find a way to downplay. There are moments, Luke said, when Mark “feels like sometimes he raised us a little bit too humble. Especially at the quarterback position, you have to be a little bit on the cocky side of humble and have to show you belong.

“Have to show you’re vocal. Show you’re that guy.”

Perhaps that’s where Drake could stand to grow the most. In developing an edge. Sam Howell, Drake’s predecessor and friend and mentor, had it in a brooding kind of way. Tim Tebow had it in college, and wasn’t afraid to deliver speeches that wound up as rallying cries, or on plaques. Winston and Manziel had it, arguably to such extremes that it proved detrimental.

“I think it’s really hard to kind of flirt with that line,” Luke said of embracing the cocky side of humble, “but I think Drake’s getting better.”

It’s in him. Mack Brown, entering his fifth season of his second head coaching stint at UNC, sees it. Drake, Brown said recently, “looks like the nice, ‘aw shucks,’ cute young guy.” And yet “he competes his tail off.” And that was part of why for so long he resisted going to UNC.

Full circle at UNC

The relationship between the Mayes and UNC now feels like one of those things that’s been around forever in Chapel Hill, like the bell tower or the stone walls. Yet it’s only 40 years old, and Mark took his time to finalize his decision to go to North Carolina in 1983.

When his sons came along many years later it took a long time for any of them to understand who their dad had been, in an athletics sense. Mark was never one for bragging or glory-days reminiscing, even in kind company. And so Beau, the second-youngest, heard about his father’s game from old security guards working high school games around Charlotte.

“Aren’t you Maye’s son?” they’d ask.

“Yes, sir,” Beau would say.

“Man, your dad was one of the craziest white boys I’ve ever seen play basketball.”

Cole, the second-oldest, only began to realize it when a neighbor showed him a football card from Mark’s short-lived days with the Raleigh Skyhawks. It wasn’t the NFL but seeing him there on a card, in uniform and looking like he could play, offered proof.

“Like damn, my dad must’ve been pretty good, actually,” Cole said. And then: “We always believed my mom was a great athlete. We had to be sold on my dad.”

In the early-80s, no college football coach had to be sold. From Dick Crum to Bobby Bowden, they all wanted Mark. At Independence High in Charlotte he became one of the most prolific passers in American high school football history. Sports Illustrated’s “Faces in the Crowd” featured him his senior year. O.J. Simpson presented him with an award sponsored by Hertz.

The day Bear Bryant died in January of ‘83 his successor at Alabama, Ray Perkins, was in Charlotte recruiting Mark. Perkins received word of Bryant’s death while watching film at Independence, where Mark had a basketball game that night. Perkins went into a room to cry alone and Mark’s dad, Jerry, told Perkins they’d understand if he needed to go back to Tuscaloosa to mourn.

“No,” Perkins said, according to Jerry’s retelling of the moment in a 1983 story in the Greensboro News and Record. “Coach Bryant would want me to stay.”

For Mark, the lure of Chapel Hill proved too strong. He arrived with the same anticipation that followed Drake to UNC almost four decades later. But then came a mysterious pain at the beginning of his sophomore year, just when he was about to become starting quarterback. An arm soreness that for months nobody could diagnose. A right shoulder in need of major surgery. Doubt he’d ever play again, only to return in 1986 after 13 months of rehab, and being unable to throw.

“Never really was the same throwing the football,” Mark said.

Without the injury, perhaps he fulfills a dream of a long NFL career. But then he never would’ve coached Aimee in a Powder Puff game after he returned to Chapel Hill to be a graduate assistant under a young head coach named Mack Brown. Aimee worked in the football recruiting office. Mark went to class on the way toward earning an MBA.

Aimee’s first thought, she said, upon seeing Mark: “He’s really cute.” Her second thought: “He’s probably married, with kids.” But he wasn’t.

Soon enough, Mark was knocking on Aimee’s door in Whitehead Hall, asking if she might like to grab dinner. Their first date was at Golden Corral. They played things slow, wary of their five-year age difference, but it wasn’t long before they knew. A couple years later, 1991, Aimee walked into the old Ham’s on Franklin Street and made sure they were carrying the Skyhawks’ game in Orlando.

After years of heartbreak and injuries, Mark finally felt healthy. He believed he could still play. The World League of American Football provided him one last chance to keep his dream alive. One last shoulder injury ended it. From that Ham’s, Aimee watched while Mark sat on the sideline, his jersey off, telling a TV reporter that his shoulder “popped out” and “it’s really scaring me.”

“You know, I’ll be OK,” he said, sounding resigned. He never played in another organized game.

“I didn’t understand why,” Mark said recently of his misfortune, but he kept the pain inside, along with the faith that one day it’d make sense. That there was a plan.

“Maybe deep down inside, he struggled with it more,” Aimee said, but he never showed it.

She’d grown up with one brother. Mark was an only child.

“We wanted a big family,” she said, and she knew Mark “would have a lot of fun coaching his kids one day.”

Luke came along six years later. And Cole 15 months after that. And Beau three years later. And Drake 14 months after that. And Mark did coach them all, in everything, but now they’re all grown and out of the house. Luke’s in Turkey, still playing professionally. Cole’s working in finance in Charlotte. Beau’s a senior at UNC.

Just yesterday, it seems, Luke was getting up shots in the Smith Center after games his freshman season, Mark there to rebound for his oldest son. Somehow almost eight years went by and now here’s his youngest, the only one who chose football, arriving at a moment of great expectation.

Mark isn’t a sentimental type. He hasn’t much thought about the symmetry between him and Drake — same position, same school; the full circle of it all.

“I guess I need to enjoy that more, don’t I,” he said.

Choosing the Tar Heels

For years Drake told Scott Chadwick, his football coach at Myers Park High in Charlotte, to deliver a message to the college coaches who called about him. Drake wanted them to know that whatever assumptions anyone had about his future were probably wrong. He wasn’t continuing the family legacy in Chapel Hill.

Part of it, as Chadwick put it, was that Drake “didn’t want to go somewhere and be Luke’s little brother. And he didn’t want to go somewhere and be Mark’s son. He just wanted to be Drake.” Another part of it had roots in sibling competition. When Roy Williams and others came around to recruit Luke when he was in high school, Drake, then in sixth grade, offered a bold prediction.

“You watch,” Luke said, remembering what his youngest brother told him. “When I’m getting recruited, Coach Saban’s going to be sitting in our living room.”

Sure enough, years later, Nick Saban made his way to Charlotte, the second Alabama head coach to travel from Tuscaloosa to recruit a Maye at quarterback. By then Drake had already committed to Alabama, in the summer of 2019. He might’ve remained so if not for Saban landing Bryce Young, and Mack Brown’s familiar and reliable pitch about family and staying home.

Had Drake gone to Alabama he would’ve been among the many high-profile prospects who join the Crimson Tide every year. He would’ve faced unusual pressure in a place arguably at the epicenter of college football’s popularity in the South. He would not have had a chance, though, to elevate Alabama football; to take it somewhere it’d never been.

He has such an opportunity at UNC and, indeed, “It’s a lot of weight,” said Mark, who has tried to take Drake back to a little more than a year ago, when “he was under as much pressure then as he is now.”

The difference is everyone expects an encore. Is it more difficult to do what Drake did a season ago, when no one was quite sure what to expect? Or is it more difficult to do it again?

Drake could’ve gone some place where it might’ve been more likely to win at the level he expects. With NIL and the transfer portal, the rumor mill ramped up, along with unsourced chatter of million-dollar offers. Chadwick, his old school coach, became an unintentional middle man.

Now at Clayton High, outside of Raleigh, Chadwick has sent hundreds of players to college and also worked for a while with the football program at Maryland. He knows folks. And indeed, he said, one regular contender for the College Football Playoff contacted him and made clear it’d welcome Drake, if he wanted to leave.

Yet “it’s laughable how overblown” some of the rumors were, the dollar amounts, Chadwick said.

Still, Drake had to address it. He and his parents at the end of last season went to dinner at Stoney River, an upscale steak chain in Chapel Hill. The conversation turned toward Drake’s thinking. Mark worried others might overhear them but it was a short talk.

“I can never leave this place,” Drake told his parents, according to Aimee.

He decided that whatever awaited him in college football would happen at UNC, regardless of how easier he might have it someplace else. It fit into a Maye mantra, of sorts, a willingness or even a need to embrace a challenge.

“That’s always been our mindset, the family,” Luke said. We don’t really back down.”

Brothers’ bond remains strong

At the ACC event last month in Charlotte, Drake often walked the halls alongside a couple teammates, John Copenhaver and Cedric Gray, and Mack Brown, who recently turned 72 and who just might be coaching his last great quarterback in a career full of them, from Vince Young to Colt McCoy to Sam Howell. Drake and Brown and the rest took turns behind different cameras, filming television promotional content to be aired throughout the season, answering silly questions.

Drake, for instance, had a difficult time coming up with a “guilty pleasure TV show,” as a producer asked. But he did reveal he plays his share of online chess and prefers to keep his pregame meals light: fruit, strawberries, a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. A pregame PB&J, especially, Drake said, “And I’m good.”

Meanwhile, Brown gushed about Drake’s competitiveness and intangibles and said weeks later, days before the start of the season, that “I don’t like Drake. I love Drake.” It’s not a stretch to say Brown played an important part in Drake’s larger story, given he hired Mark to be a GA all those years ago and unknowingly set him on his path toward meeting Aimee.

“I love that family,” Brown said, continuing his thought. “They stand for what’s right in everything they do. ... Look at that family. They are a pedigree of champions.”

Sports reveal such things, whether nature or nurture is most responsible. How does a late sixth-round draft pick out of Michigan, relatively unknown, go on to become the greatest quarterback in NFL history? How does a first-round pick and Heisman Trophy winner out of Texas A&M, blessed with all the physical talent imaginable, flame out of the NFL after two seasons?

How does a can’t-miss prospect ... miss, in the most defining of defining moments? How does someone just about everyone missed on make one of the most memorable shots in UNC basketball history? Pedigree is not all of it but it helps explain some of it. It helps explain how Luke delivered in Memphis that day, and also how after he did, “it didn’t really change Luke at all,” Beau said.

“Same guy, same great older brother, same competitive guy, same guy who wants to catch up on everything, like we all do. He was just another dude, no matter what. Whether he was All-ACC or doing well in school and playing basketball ... he was just our older brother, you know?”

Luke, as the oldest, embraced his role as protector and example-setter. Cole self-identified as the antagonizer. Beau, Aimee said, is the old soul of the bunch, a deeper thinker shaped in part by the nine knee surgeries that limited his ability to play sports.

He still walked onto the UNC basketball team last year but then left it in part because he didn’t want to miss any of Drake’s games this season. Beau is one of Drake’s housemates, along with a friend of theirs from back home, and he feels the greatest responsibility to be there for Drake. Besides, Beau said, “Whenever his head gets too big, I try to knock it down a little bit.”

Like Luke after Memphis, there’s been no indication that last season’s success — the video game numbers, the emergence on a national stage — changed Drake. He still drives the same pick-up he’s had since high school. Still dates the same girl he’s dated since middle school. Still needs reminding sometimes about taking out the trash at home, but Beau said he’s getting better about that.

Indeed, the Maye boys have come a long way, in their own ways. They still bust chops and the mutual roasting remains endless but it’s no longer about things as trivial as scrambled-egg consumption (most of the time). Now it’s making fun of each other’s press conferences or lack of national title rings. Luke and Cole like to remind Drake they have two between them.

To which Drake can point to an ACC Player of the Year. And what if he wins the Heisman?

“He’s always joked about that,” Luke said, somewhat dismissively. “He’s said, ‘What about an individual award?’ I don’t know. Me and Cole got to think on that a little bit.”