Don Shula coming to Miami and 17-0 should never have happened. It was crazy luck. Or fate | Opinion

Don Shula’s legacy will take a hit soon enough. It is within sight now. Miami Dolphins fans old enough to hold such things dear should brace for it. Records are made to be broken and so forth. Time takes care of all that.

Within two or three seasons Patriots giant Bill Belichick almost certainly will surpass Shula for NFL career regular-season victories and overall wins including playoffs. Belichick already has a record six Super Bowl championships to Shula’s two.

Yet the reputation and legend of the Dolphins’ and Miami sports’ icon remains strong and immovable as a mountain.

Such a big part of that of course is the singular, unmatched Perfect Season being celebrated this year on its 50th anniversary. Almost 1,500 times over a half century, NFL teams have begun a season trying to end it without blemish. Just as 52 seasons of teams prior to 1972 had failed to do so.

Shula’s 17-0 stands alone, for all time.

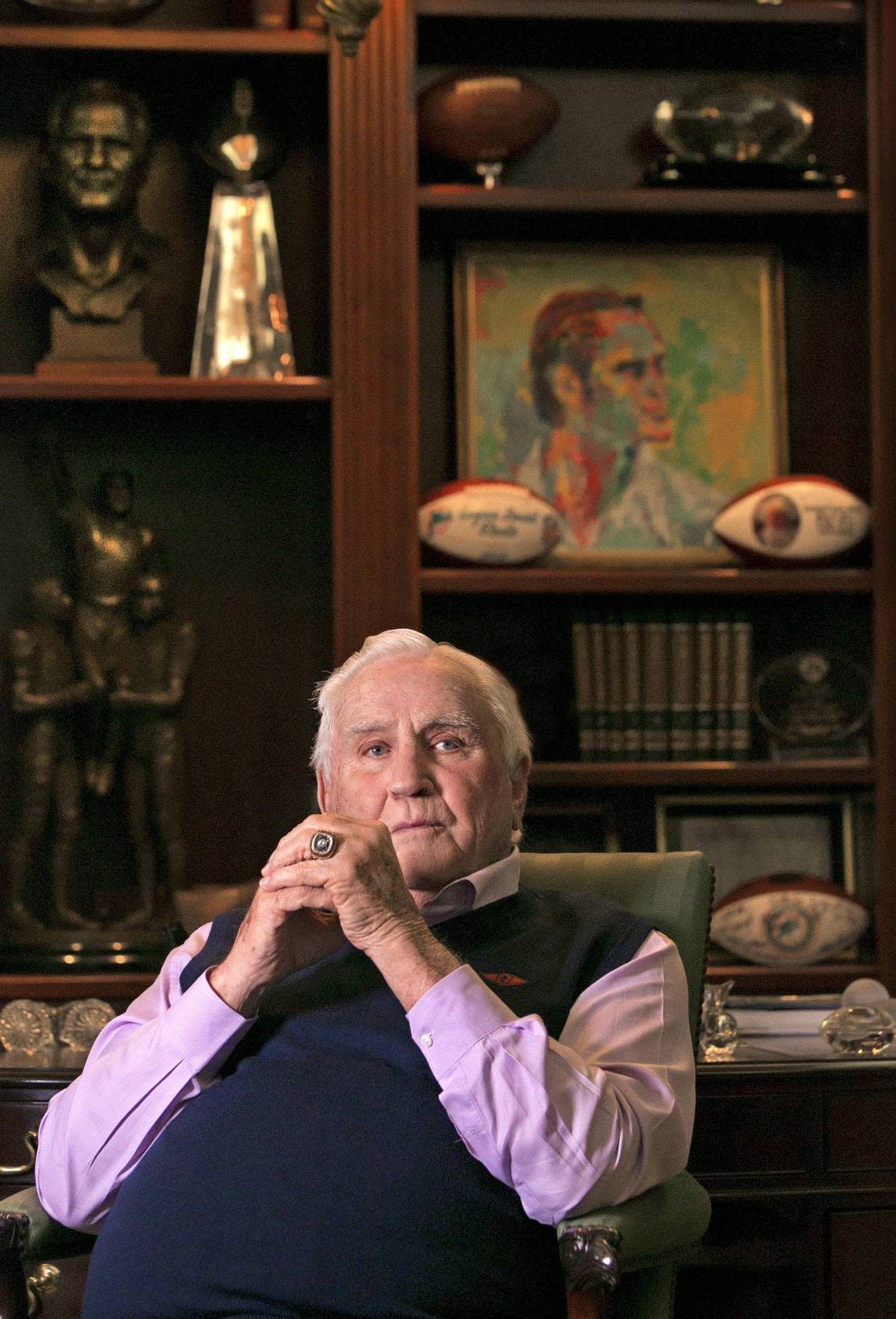

Late in his life, in our last interview together, in his memento-filled den at his home in Indiana Creek outside of Miami, I mentioned that he is the only coach, ever, in any sport, associated with the word “perfect.”

His grin warmed my heart. He was nearing 90.

“I kind of like that!” he said.

The record that never existed before Shula created it will never be surpassed, only — maybe, someday — tied. It will always belong to its creators.

“Each year, as the last undefeated team loses, we come back to life,” says Larry Csonka, smiling. “It’s like the dust blows off and we’re up and we’re talking. I don’t know how to explain it other than to say it gives you the feeling, as you reach antiquity, that you’re still in there. There’s still a competition going on.”

It is more than the Perfect Season though that makes Shula eternal in South Florida’s heart. But what, exactly?

Is it that in 26 seasons in Miami he had only two losing records, creating a culture of relentless competitiveness and playoff expectations? It is.

Is it also that Shula personified integrity, with nary a blemish let alone scandal in what he did on the field or off? It is that, too.

PERFECT MEMORIES

Join us each Wednesday as we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the perfect 1972 team

And it is so much more. Things that over time have become underappreciated.

Shula ended what had been a segregated locker room before he arrived in 1970. Suddenly Black and white players were paired as roommates on road trips.

“I don’t remember my dad ever taking about it. He didn’t think of it as anything special,” son Dave Shula told us. “But Miami then was not many years removed from Virginia Beach being a Black breach and all that that kind of stuff. I don’t think my dad is given enough credit for seeing players as people. People don’t see him as being an equal rights crusader, but his actions bespoke how he felt. He realized the Dolphins could be a unifier for the community, all faiths,colors and economic backgrounds together to rally around a team.”

Larry Little grew up in Miami, a Booker T. Washington kid. He could walk from his house to the Orange Bowl.

“During that time it was segregation and we had to sit in the bleachers,” Little recalls. For him to be traded to the Dolphins and find no segregation within the team, “It means a great deal to me,” he says, still using the present tense.

Shula also was a forerunner of situational substitution, which would become de rigeur across the NFL. Raiders coach John Madden once told me he spent hours on the phone with Shula picking his brain on the theory and practice.

This, too, from Little: “Before Shula came, we were on the other sideline. But when he came to Miami he realized we could benefit by being the team that’s not in the hottest part of the stadium. So he changed sidelines. He moved us to the other sideline, so the other team can suffer like they’re still doing now.”

So many of us in South Florida grew up with, were raised by, the granite-jawed figure steady on the sideline. He was a timeline in our lives. For me, across Shula’s 26 seasons, I went from being a 16-year-old kid banging around high-school to a 42-year old married father of two.

My own father adored Shula. Late in my dad’s life l got to introduce him to the great coach, then late in his career. It was as if I had introduced a devout Catholic to the Pope. Shula could not have been kinder to my father or more gracious with his time.

He was a volatile man as a coach, but soft as a father and grandpa.. I recall a practice at the old St. Thomas University facility ended with him loudly blistering a player over some football sin or another, then turning to his a grandchild running toward him. A grin washed over the coach’s face as he lifted the toddler high as he could by both arms.

“Hang time!” Shula all but sang.

Shula was a man who could get angry but did not hold grudges.

For a while I used to refer to Shula in print as “The Cobbler,” a ridiculous play on his nickname, “Shoes.” He didn’t get it and asked me one day after practice. I have never stammered so much in my life to explain. “That’s horse----!” he boomed, and stormed off.

An hour or so later Shula found me alone, grinned, shook his head, clasped me gently on the back of the neck, and walked away. The clasp on the back of the neck , it meant we were OK.

We all know what Don Shula meant, to the Dolphins and NFL history, to South Florida, and in so many of our lives.

But how did it happen? And why?

This has been under-explored — the very first seeds of 17-0.

How it came to be was enough to make you believe in fate.

Or in faith — the idea that things happen for a reason.

It didn’t start after the expansion Dolphins’ losing season of 1969, when owner Joe Robbie decided to make a coaching change.

Maybe it started much earlier, around the fall of 1961, in a living room in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, just northwest of Pittsburgh.

A University of Alabama offensive coordinator on a recruiting trip knocked on the door of a home.

The coach was named Howard Schnellenberger.

It was Joe Namath’s house.

Schnellenberger, who of course would go on to win the Miami Hurricanes’ first national championship in 1983 and before that serve on Shula’s staff during the Perfect Season, sealed the deal with Namath, who would star for three years at Bama, helping Bear Bryant to the 1964 national title.

The legendary Bear and the Crimson Tide machine — percolating long before Nick Saban — would shape Namath into a major pro prospect.

In the 1965 draft the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals selected Namath 12th overall. The AFL’s New York Jets made him the No. 1 overall pick.

The Cardinals agreed to Namath’s demand — $200,000 and a brand new Lincoln Continental — but insisted he not play in that season’s Orange Bowl game and risk injury. But Namath wanted to come to Miami and play in the OB. When the Jets offered a three-year, $427,000 deal, a record at the time, Broadway Joe was born.

Four years later Namath, who had guaranteed it to a handful of reporters including the Miami Herald’s Edwin Pope on the pool deck of a Miami Beach hotel, led the Jets to the most shocking upset in the history of the Super Bowl, beating the Baltimore Colts at the Orange Bowl.

Beating Don Shula’s Colts.

The loss engineered by Namath was a humiliation that drove apart Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom and Shula.

If the Colts had beat Namath as expected, Shula “absolutely” would have stayed in Baltimore, said Dave Shula. “My dad loved Baltimore and we did as a family. But sometimes out of adversity comes amazing change.”

At that same time, Joe Robbie was fed up with his coach, George Wilson, and planning a change.

He didn’t go after Shula, though.

He went after someone bigger.

“Early 1970 after the ‘69 season, I’d have been 14 going on 15, and the talk around the house was that we were going to get a new coach,” Tim Robbie, Joe’s son, recalled. “My dad was very intent on making a splash, not just hiring another guy. He wanted a big-name coach with an impeccable resume. He locked on to Bear Bryant. I remember him visiting our home, and it was kind of like having the Pope over. He had on the houndstooth hat. He mumbled a hello.. My dad took him to the den and shut the door.”

When the door opened, Robbie was convinced he would soon be introducing Bear Bryant as the Dolphins’ new coach.

“I can say with close to if not 100 percent certainty, they had a handshake deal,” Tim Robbie said.

The powers in Tuscaloosa sweetened the deal,though. The Bear changed his mind.

Joe Robbie then went after his second choice, the coach who was only available because Namath had just pulled off one of the great upsets in sports history.

Only when Bryant changed his mind did Robbie target Shula — and only then because Miami Herald sportswriter Bill Braucher, who knew Shula from John Carroll University, passed along that Shula might be on the outs in Baltimore. Braucher told the Herald sports editor Pope, who told Robbie.

The NFL would make Miami give up a first-round draft pick for “tampering” in its back-channel communication with Shula.

It would be one of the biggest bargains in sports history.

Shula’s eldest son, Dave, was 10 going 11 at that time in early 1970.

He started chuckling at the memory. He was recalling the sight the first time he went to class at Baltimore’s Maryvale Elementary School the day after his dad leaving for the Colts for Miami had been announced and was the talk of the town.

“Kids had put signs in all the windows saying, ‘Dolphins suck!’,” Dave said, and laughed.

So ... what if?

What if Schnellenberger had not successfully recruited Namath to Alabama?

If Namath had not become a top draft pick and signed with the upstart AFL?

If the Jets had not fulfilled his “guarantee” by beating Shula’s Colts?

If Bear Bryant had not changed his mind?

Joe Robbie settled for his second choice in Don Shula.

It worked out OK.

No. Fifty years later, it can still be said:

It worked out perfectly.