Does video at UM frat show hazing? Lawyer behind Florida law has this to say about it

A video that appears to show several people chugging milk until they eventually spew liquid onto a University of Miami student is evidence of hazing and could have been much worse, said the author of Florida’s anti-hazing law.

Miami attorney David W. Bianchi, a national leader in hazing litigation with over 40 years of experience, told the Miami Herald Friday that the recorded incident “meets the definition of hazing” under state law even if the student participated voluntarily.

According to the trial lawyer at the firm Stewart Tilghman Fox Bianchi & Cain, criminal charges wouldn’t likely be filed because no one appeared to be hurt.

What is the University of Miami saying?

The Coral Gables university says it is investigating the incident, but has not called it hazing.

“The university could most certainly take steps to discipline the students involved,” Bianchi said.

UM said Thursday it received several widely shared videos depicting conduct violations, one of which the school confirmed was authentic.

“A full investigation is underway,” the university wrote in a statement.

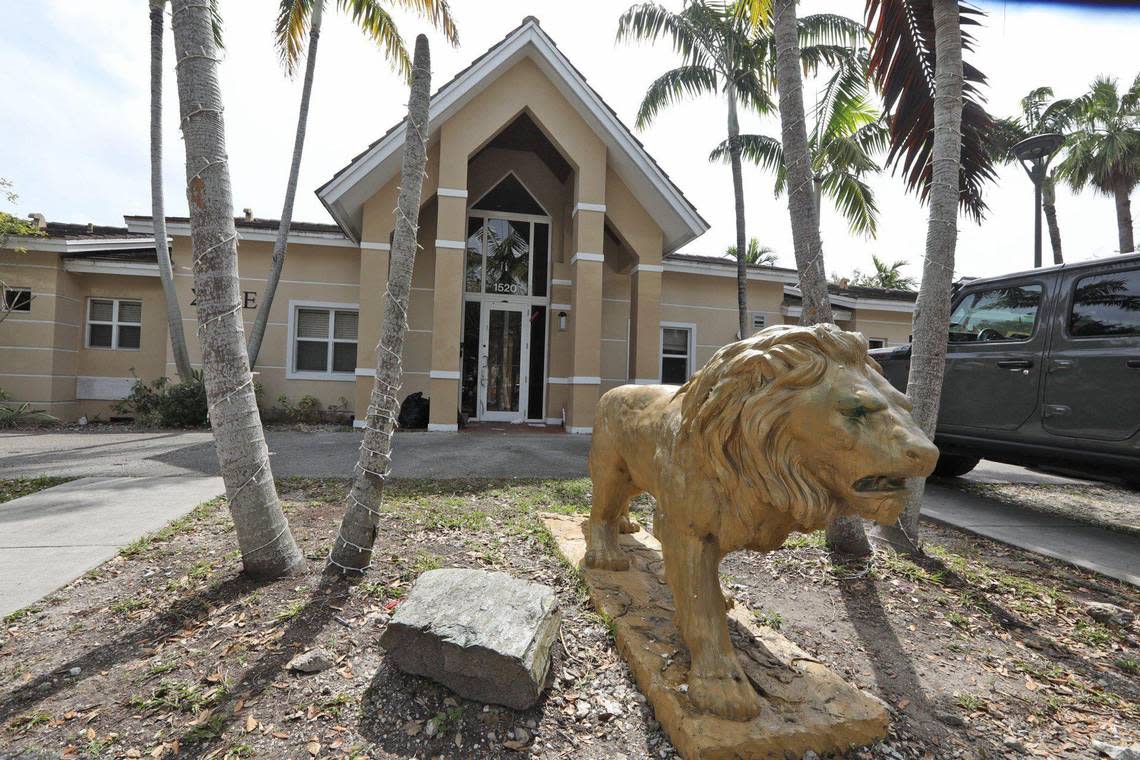

Officials did not specify which fraternity is under scrutiny nor did they detail when or where the violations took place. However, the investigation comes after the Miami Hurricane, the university’s campus newspaper, first reported Thursday that the fraternity Sigma Alpha Epsilon was involved in hazing allegations.

A video revealed members of the fraternity participating in a possible hazing incident in their house’s backyard, the college newspaper reported. A man stepped into a trash can while three others crowded around chugging milk until they eventually spit or vomited on the student.

The Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity Service Center, the fraternity’s national chapter, told the Miami Herald it received a report stemming from an alleged incident involving the University of Miami chapter.

“We have placed our Chapter on a Cease & Desist and are working jointly with the University to investigate,” the national chapter said.

The local UM chapter did not immediately respond for comment.

Coral Gables police spokesman Sgt. Alejandro Escobar said no one had filed a police report with the department nor with the university police as of Friday morning.

Will the students be disciplined or charged?

It is unlikely that the students will be criminally charged because the alleged hazing did not seem to have hurt or killed a student, Bianchi said. According to the trial lawyer, prosecutors have discretion on whether charges are filed.

“However, the university can most certainly take steps to discipline the students involved because every university has an anti-hazing policy,” he said.

Following an investigation, Bianchi said the university could send letters with a hearing date to students who participated. At the hearing, the students would have an opportunity to defend themselves before the university makes a final determination, which could range from taking anti-hazing courses to suspension, he said.

“I would expect the national fraternity to take disciplinary action as well,” he said.

Following an investigation, Bianchi said the national fraternity could discipline members or, in extreme cases, withdraw the charter of the local chapter and close it permanently. The university could also remove the chapter from campus, typically depending on the severity of the case, he said.

Bianchi warned what could seem like a harmless hazing to some could quickly turn deadly either unintentionally or when, in instances, the person harms himself after public humiliation.

“Fortunately, this was discovered before the consequences became too severe,” he said. “Nevertheless, the university is going to want to send a message to all the Greek organizations on campus that any form of hazing will not be tolerated.”

Prominent hazings in Florida

Florida anti-hazing laws have strengthened in the last decades after several college students died during dangerous fraternity activities.

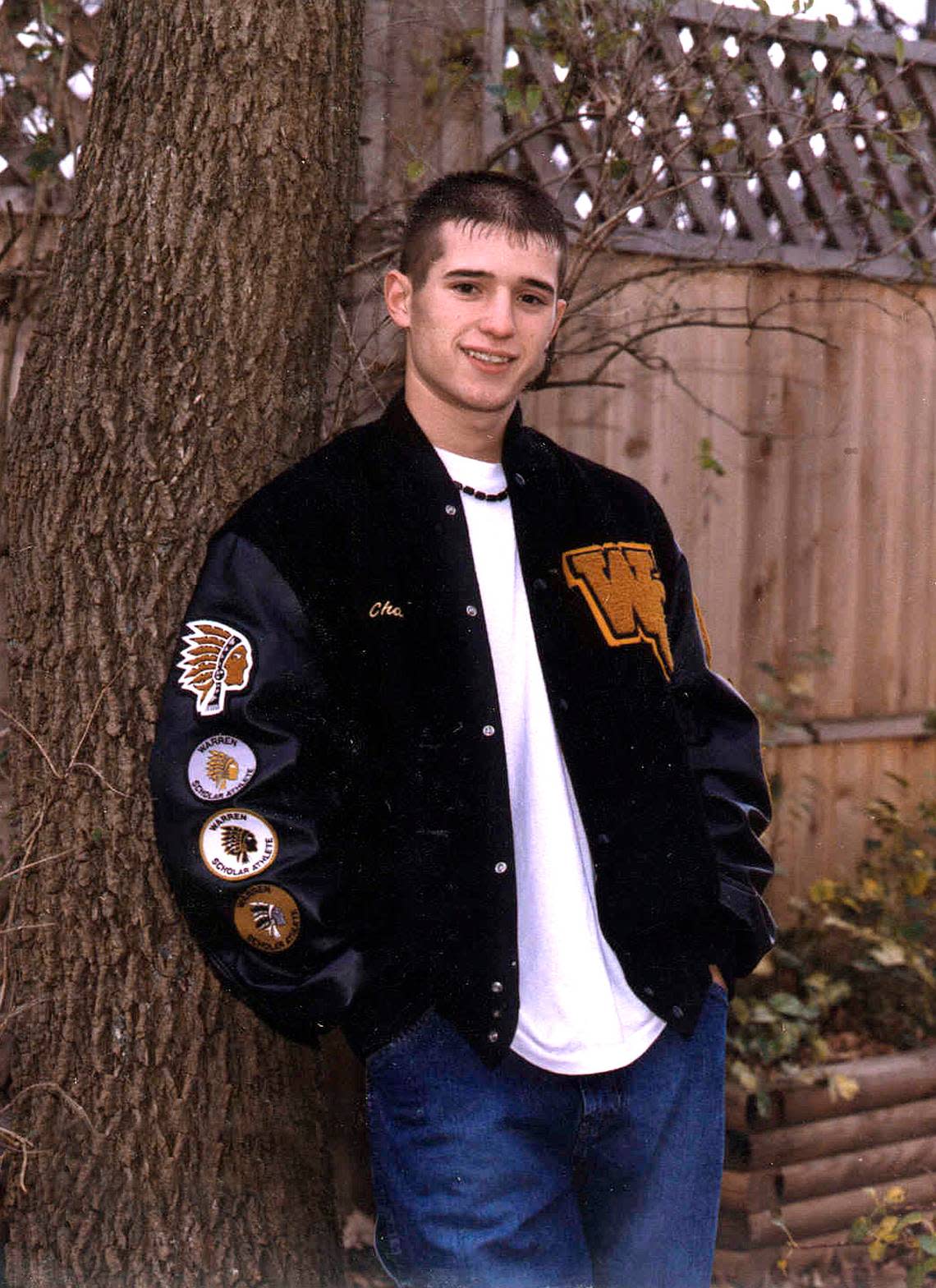

One of them, Chad Meredith, 18, drowned in Lake Osceola, near the University of Miami campus, after Kappa Sigma leaders encouraged him to drink an excessive amount of alcohol at their fraternity house to later go for a swim in November 2001.

Despite the excessive drinking, top chapter fraternity officials told Meredith to follow them into the dark and cold lake around 4 a.m., knowing that the university had a rule against swimming there, Bianchi said. According to Bianchi, It was later discovered that the blood alcohol level of Meredith, a freshman from Indiana, was nearly two times the legal limit.

His “family was very excited because they had never had anyone in the family go to college before,” Bianchi said.

Meredith was halfway into the lake when he had a panic attack and started screaming for help, Bianchi said. But instead of the fraternity officials coming to his aid, Bianchi said one of them swam toward Meredith, saw that he was in trouble and swam away.

Divers then found his body near the shore; he had drowned in less than seven feet of water, Bianchi said. The lawyer added that Meredith would have lived if the fraternity officials had helped him.

History of anti-hazing laws in Florida

In 2004, following a one-week trial led by Bianchi and the firm, a Miami jury awarded $14 million to Meredith’s parents for his death.

But Bianchi did not stop there.

He then wrote the Chad Meredith Act, which made hazing a felony if it results in serious injury or death or a misdemeanor if it puts someone at risk of getting injured. The bill also said the victim’s willingness to participate in the hazing is not a legitimate defense, Bianchi said.

“Hazing is all about peer pressure and not wanting to be ostracized,” Bianchi said. “So, you would go along under circumstances where you would not otherwise agree.”

On June 7, 2005, Florida Gov. Jeb Bush signed it into law at the University of Miami.

After Florida State University freshman Andrew Coffey died from acute alcohol poisoning because of a hazing tradition at Pi Kappa Phi in November 2017, nine fraternity members were criminally prosecuted for their role in Coffey’s death under the Chad Meredith Act, and they all went to jail.

Feeling that Coffey would be alive today if just one of his fraternity “brothers” had alerted authorities sooner, Bianchi and attorney Michael Levine wrote a bill giving amnesty to the first person to call 911 and stay with the hazing victim until paramedics arrive. Gov. Ron DeSantis signed Andrew’s Law on June 26, 2019.

“Ask any parent who has lost a son to hazing, and they would all tell you that they would rather have their son back than prosecute the guy who did it,” Bianchi said he told a legislator at the time.