Does your kid qualify for special ed? Here’s how to navigate the system in Texas schools

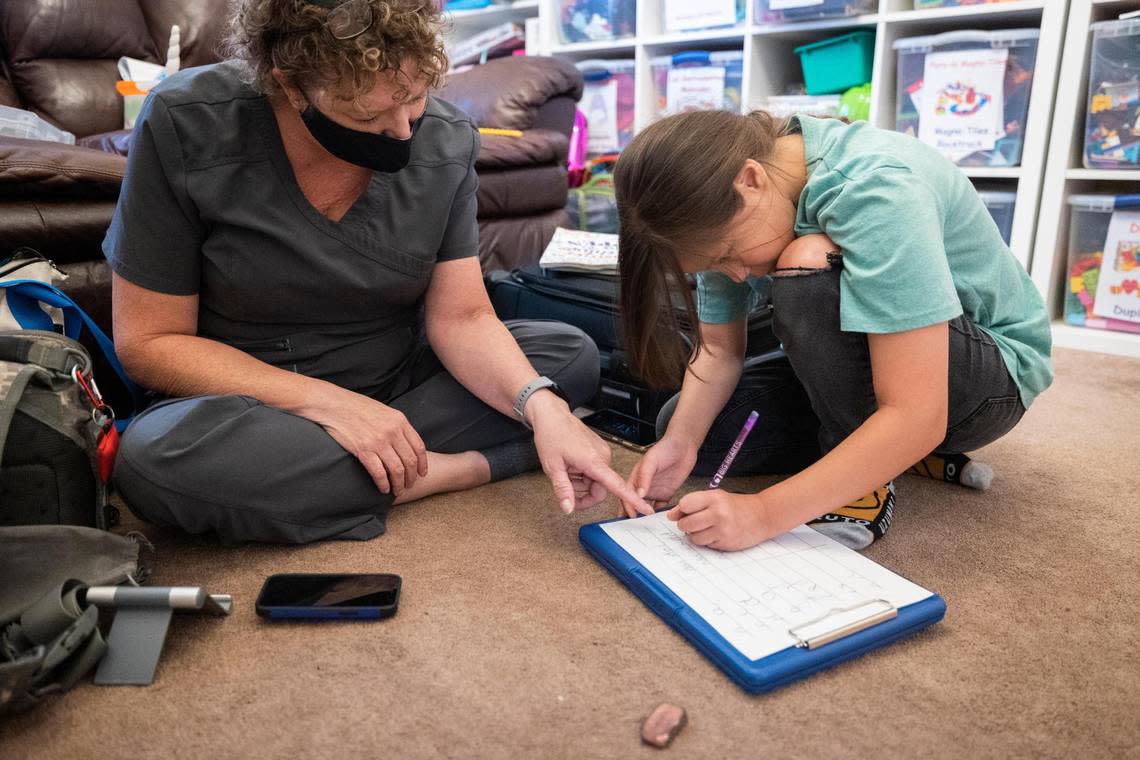

Parent involvement is crucial during the process of determining special education eligibility, experts say.

It’s important that parents know their rights throughout the process, where parents and district staff play an equally important role, said Kym Davis Rogers, a litigation attorney at Disability Rights Texas, a special education advocacy organization.

[Para leer este artículo en español, vaya aquí.]

Students are eligible for special education services if they have a disability and that disability prevents them from succeeding in the classroom, according to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Either a parent or a school district staff member can request an evaluation for special education.

The process may begin when either party recognizes a student isn’t advancing in the classroom or isn’t performing at grade level.

The first step is to try a non-special education intervention method such as one-on-one tutoring or practicing an online reading intervention program, among other options.

If academic progress still lags, the evaluation process may formally begin. If parents choose to start the process, they should request an evaluation from the district in writing, Rogers said. The request can be made in the parents’ native language.

Parents have to give consent to start an evaluation if the district requests the evaluation, and consent can be withdrawn throughout the process.

After a written request is made, the district has 10 days to respond, either agreeing to start an evaluation or declining. The district’s response should include more information on how parents can challenge the decision if the district declines the request, Rogers said. The evaluation should start within 45 days of responding to the parent if the district decides to move forward.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requires a complete, individual and multidisciplinary evaluation. It should include a variety of opinions from people such as medical doctors, psychologists, teachers and speech pathologists, among others.

Evaluations should be done in the student’s native language. If the student is in a bilingual program or their first language is Spanish, districts will sometimes evaluate students in both languages, Rogers said. If the evaluation isn’t done in the appropriate language, parents can request that it be done again. Parents can also request that an independent evaluation be done and paid for by the district, if parents disagree with how an evaluation was conducted.

After the evaluation is complete, the district has 30 days to schedule an Admission, Review and Dismissal committee meeting, where the committee will review the results of the evaluation, determine special education eligibility and, if eligible, put together an Individual Education Plan. The plan should include all necessary accommodations and guidelines for that student’s particular education needs, Rogers said.

“Parents are equal participants” in an Admission, Review and Dismissal meeting, Rogers said. “They are their child’s best advocate. They raise their child, ... they know the strengths of their child, ... and they can help develop that plan for their child.”

Parents are entitled to receive all relevant information to be able to actively participate in the Admission, Review and Dismissal meeting in their native language. This could mean having a translator or interpreter present at the meeting and receiving a copy of the evaluation in their native language, Rogers said.

If parents don’t agree that the recommended district plan is how their child might succeed, they can file a complaint with the Texas Education Agency or they can file for due process, which is an administrative hearing to challenge the recommendation.

An Admission, Review and Dismissal meeting is held annually, but parents can request a meeting before the year is up if their child isn’t progressing in school or they suspect their plan isn’t working.

The process can intimidate any parent, but even more so for a parent whose first language is not English, said Theresa Moffitt, patient liaison with Patricia Martinez therapy services in Arlington.

Moffitt often attends meetings and guides Latino parents through them. She recommends that parents ask a lot of questions about their evaluation, provide insight into the child’s behavior at home and make an effort to get a clear understanding of all of the district’s recommendations.

“Don’t be afraid to ask, ‘What does that mean?,’” Moffitt said. “Parents need to ask, ‘What does that look like?’ ”