How does Anne Lamott define love? She spent a book trying to do just that

It takes Anne Lamott a few words to say what the rest of us spend our lives searching to express.

Perhaps that's why her books — which she's been publishing since the 1970s — are received as wisdom distilled. She's previously expounded on creative writing ("Bird By Bird), faith ("Plan B"), prayer ("Help Thanks Wow"), courage ("Dusk Night Dawn"), mercy ("Halleujah Anyway) and more with her signature big-hearted wit.

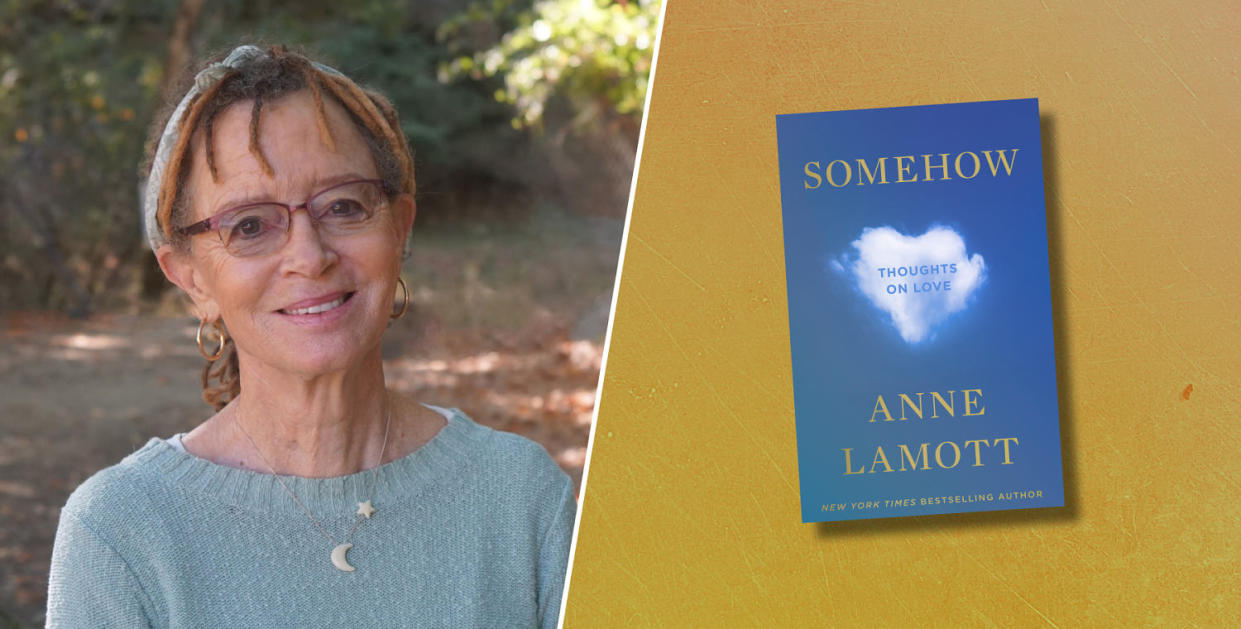

In her latest, "Somehow," she goes after perhaps the most daunting of all topics: Love.

A notable fiction writer first, Lamott moved into memoir with the release of her 1993 book, "Operating Instructions," about being a single mom. Since then, she's written about her journey with addiction, Christianity, becoming a grandmother, the creative process, getting married for the first time as a senior citizen and so much more.

Below, Lamott speaks to TODAY.com about where she finds hope and inspiration.

You've written about big topics like faith and mercy. Why love now?

I wanted to leave something behind for my son and grandson that would contain every single thing that might help them no matter what the future holds. I have very grave concerns about the climate. I started writing these pieces that I felt were very hard-fought wisdom, but sort of funny at the same time. It turned out all of them had something rather to do with love. So that's how I came to write a book on love. It was an accident.

You written about so many different kinds of love. What does it mean to you?

I always think of what Mr. Einstein told us: There's really only one thing moving at different speeds, and it's energy. Because I'm a believer in a different reality besides the visible, I believe that there is this energy inside of us and surrounding us that we're all made of, and we're made for it, and we're called to it. We have it to offer to those who are feeling frightened or empty.

I think of love as this tender-hearted gentleness of feeling from the heart in the world.

You call yourself 'the world's worst Christian.' What do you mean by that?

The great novelist Gabriel García Marquez said we have our public self and our secret self. My public self is very loving and generous. To be a Christian means to follow this revolutionary, brown-skinned leader from the Middle East. And he says, "Feed everybody and get everybody water. And if you don't know what else to do, maybe sit quietly and pray. And he frequently says, I really think you need to eat, you seem very tense. Why don't you go down to the water and wait for the next boat and fish to come in? And we'll talk later."

But in my secret self ... oh, I feel I'm so ambitious, competitive, judgmental. I get so jealous. Those have been my crosses to bear.

I just am grateful that my mind doesn't have a PA system because I talk and preach goodness and kindness to, especially to people who are hurting, which is most of the people in the world. Then in my mind, I'm just scrambling and striving to get ahead of everybody. Especially with a book coming out, I feel like I'd be one of the people on the Titanic that is pushing even older old ladies out of the way so I could get to one of the lifeboats. So I don't pretend to be a good Christian — I just happen to really love Jesus and to have found a home in him.

Has your understanding of God changed?

It changed when I got sober. When I was using drugs that gave me visions of the ethereal and celestial and took me deep into myself, where there was something light, colorful and lovely.

Then I got sober and I started to experience God as the group of drunks helping me stay sober one day at a time.

I just see God as love. That's what I teach my Sunday school kids. Love is God. When you see loving, generous acts between people, that's God.

That's the movement of grace in our lives. When you feel generosity and surrender and stamina, that's the movement of grace. I experience grace as a spiritual WD-40. When you're clenched up, knotted up, then something very mysterious spritzes you — it's often some form of love.

I think I have the theological understanding of a bright second grader, and I don't care.

Your books appeal to people who may feel alienated from the church. Who do you feel like you're speaking to with your books?

I think there's one mountain, which is union with the sacred, the holy, the source. I think there's many paths up that mountain.

Many people who who come to my readings or who read my books ran screaming from their cute little lives or fundamentalist families, where they were told that they were garbage or that if they lived this way, loved this way, behave this way, they weren't loved and they weren't accepted, and they were going to rot in hell for all eternity.

It must be really nice to be that sure of yourself. I'm not. Like I tell my Sunday school kids, whatever age they are, I say, "You are loved and chosen as is. You don't have to do anything different for God to love you or me to love you. You don't have to become who everybody thinks you should be when you grow up. You are loved and you are chosen to be surrounded by kindness and really safe, healthy adults and all the beauty the world has to offer. And when you're sad or you've made a horrible mistake, hallelujah. Come sit down with me. Boy, have you come to the right person."

You've been writing about your life for over 30 years. What role does writing play?

I find writing very hard. I've been under a book contract since I was 24. I'm 70. I've found it hard going every step of the way. Every writer I know has a ping-pong game going on in their brain between raging ego and really bad self-esteem. Twenty books in and I still grapple with that.

The writing is a habit and the writing is a debt of honor. My dad was a writer. I watched him — the habit of him, which was that he sat in his office at 5:30 every morning, rain or shine or cold or hangover or flu, and he got his work done. Then he made us breakfast. I learned that habit: You don't wait for inspiration.

I sit down every morning and I say this little prayer: Please help me get out of the way so I can write what needs to get written. I see myself as being the secretary for the material. The material doesn't have hands. It has chosen me to get down. I take a long, quavering deep break. And no matter what, not to sound like a Nike ad, I just do it.

What keeps you writing?

It goes badly almost every single day. That's why in "Bird By Bird," I write about terrible first drafts. I don't ever feel deeply inspired. I would almost rather be watching cable news or going for a walk with my dog. But I sit down and I push my sleeves back. I feel like I got one of those golden tickets in "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory." I got to grow up to be a storyteller — try to find the truth and share it in a way that isn't preachy and condescending. I'm saying, "Got a minute? Come sit by the fire. We've been doing this 30,000 years but I don't think you've heard this exact story yet."

You wrote this book with your son and grandson in mind. Have they read it?

My husband, Neil Allen, who's also a writer, reads everything I write, and he edits everything.

I have always given my son every story that he's mentioned in since he was about 10, so that he could either authorize it or say, "No, I don't want you to tell this story." And then I did it.

My grandson doesn't read me yet. But I dedicated this book to him. He knows what I'm about. He's heard me read my stuff. But I can safely say he hasn't read a word of the new book yet except for the dedication that says for Jax.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com