Documentary series, 'The Synanon Fix,' shows drug rehab turned cult that was in Detroit

During the 1950s, Detroit, like other urban cities, had startling numbers of residents suffering from drug abuse and the city became the ideal starting ground for the country's first drug rehabilitation programs.

A new HBO Max docuseries, "The Synanon Fix," tells the story of the drug rehab program turned dangerous cult that operated in Detroit from 1969-80. The four-part docuseries premiered at the January 2024Sundance Film Festival and was directed by Rory Kennedy, the youngest daughter of Robert F. Kennedy, and contains interviews with former members.

More: Rory Kennedy's 'Last Days in Vietnam' doc captures fall of Saigon

Synanon's founder Chuck Dederich, had attended a session of Alcoholics Anonymous and felt he could replicate the sober lifestyle program for drug users. Dederich would open one of the country's first interracial community drug rehabilitation centers in 1958 in Santa Monica, California.

Dederich's rehabilitation program, Synanon, operated on the foundation of "The Game," a form of attack therapy where members were encouraged to belittle and degrade each other in the worst ways.

While its method was unconventional and extreme, Synanon was leading the way for community-based drug treatment centers — the government sent researchers and Hollywood produced the film, "Synanon," in 1965.

When members were encouraged to bring their children to live at Synanon's communes, the children of Synanon were encouraged to begin "The Game" as early as 4 years old.

“The keynote of The Game was savage, angry verbal attacks on each other — ridicule, destructive attacks with no holds barred," said a former member in a 1978 interview with the New York Times.

By the early 1970s, Synanon ran 14 facilities across the country in California, Texas, New York, Washington D.C., and Michigan, with more than 10,000 members, according to "The Synanon Fix." But by 1974, the group that initially used attack therapy to treat drug abuse, would seek religious status and begin making a reputation as an abusive, dangerous cult.

It would later be revealed Synanon mandated the divorce of at least 230 married couples, according to a 1997 article by the New York Times, who would then be convinced into vasectomies, abortions, and remarriage. The group had assets of $30 to $50 million through grants and charitable trusts.

Synanon's run came to an end in 1978 with the arrests of Dederich and top officials who pleaded no contest to assault and conspiracy to place a 4½-foot rattlesnake in the mailbox of a lawyer that had successfully sued Synanon; the lawyer was bit and sent to the hospital.

Dederich took a plea deal where he gave up control of Synanon in exchange for serving no jail time. But according to "The Synanon Fix," while he had legally passed control over to his daughter, he still ran things behind the scenes.

Related: Michigan couple disputes cult claims made in Netflix docuseries on Twin Flames Universe

By 1980, a federal court identified more than 20 cases of assaults linked to members who had been beaten for defecting from Synanon and bought more than 150 pistols and 660,000 rounds of ammunition. In 1984, a federal judge declared the organization an advocate for terror and violence.

Outside of the U.S., Synanon had established branches in West Germany, Malaysia and the Philippines — the German branch remains open today.

All about Synanon's Detroit presence

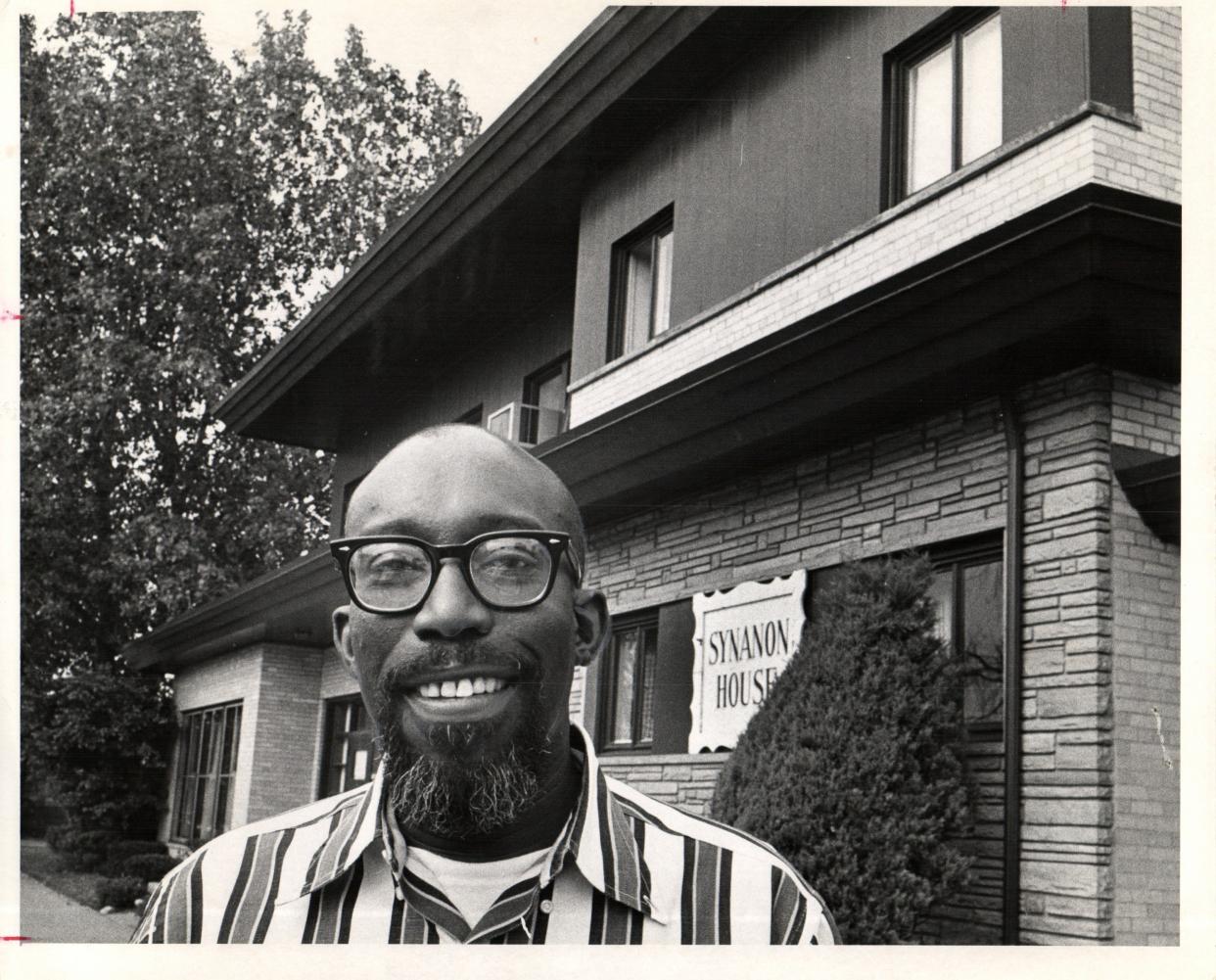

Synanon started its Detroit footprint with an $80,000 mortgage loan from the National Bank of Detroit in December 1969, according to the Wayne County Register of Deeds. Synanon would use the loan to purchase a three-story property at 18940 Schaefer Highway, just south of Seven Mile Road on the city's west side, for $100,000 from The Furniture Club of Detroit — the location would serve as Synanon's main Detroit facility until 1980.

Synanon would also rent and lease multiple properties around metro Detroit from 1967-79. The group first landed in a home in the city's Boston Edison district; but was kicked out within a year due to neighborhood complaints, said Laura Kennedy, archivist with the Detroit Public Library Burton Historical Collection.

They also operated out of a location along East Jefferson near Riverside Apartments, along West Seven Mile, and on Livernois in Ferndale. In 1979, Synanon listed its address as 1300 Lafayette, a residential cooperative in downtown Detroit.

Synanon's final attempt at expanding its Detroit presence was the purchase of the Cass Avenue Funeral Home in 1979 for $53,142.70. Once again, community backlash prohibited the needed rezoning of the historical structure and Synanon sold the funeral home, built in the early 1890s, to the Art Center Music School in 1981 for $80,000.

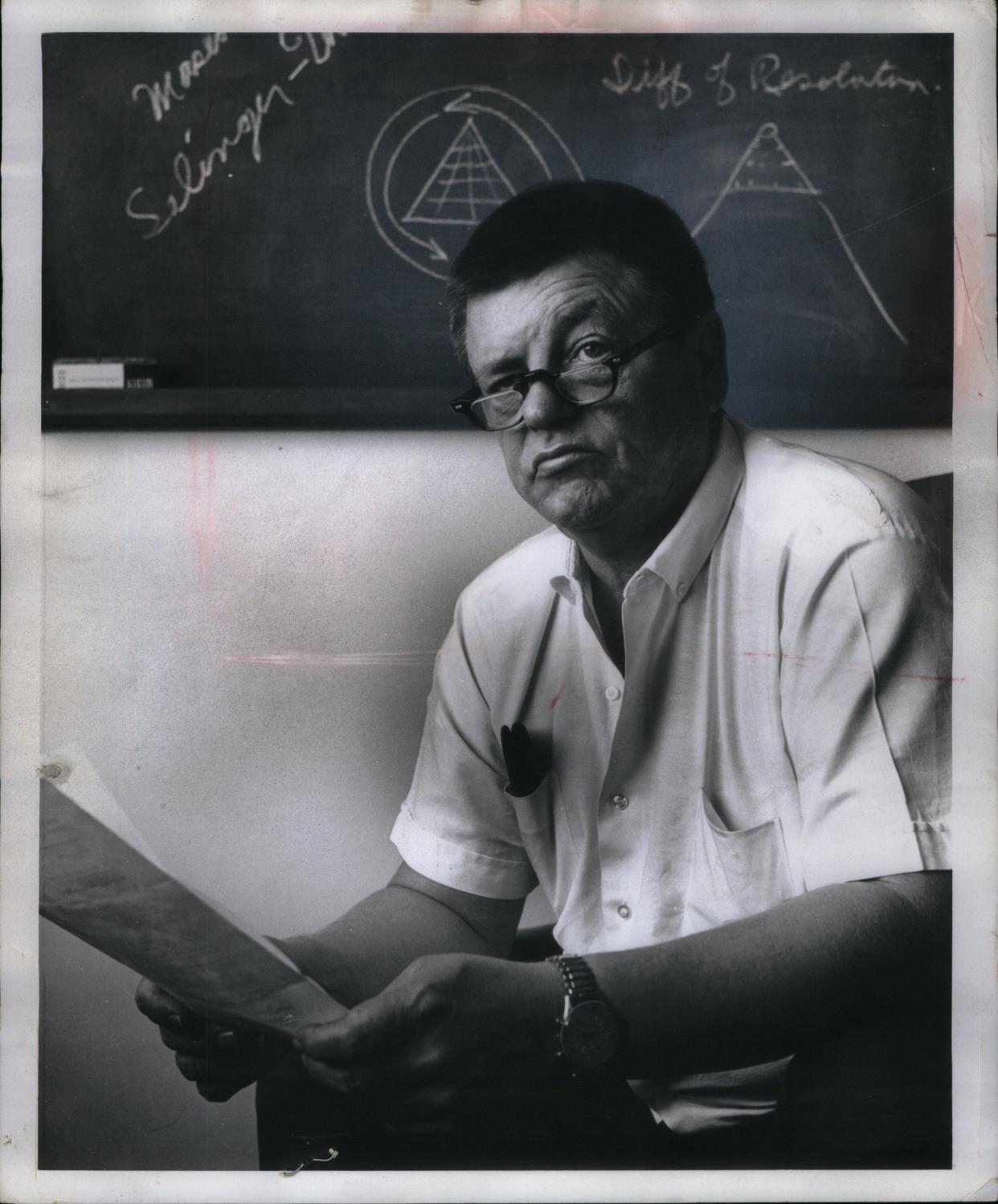

At the February 1970 Governor's Conference on Drug Dependence and Abuse, then-Michigan Gov. William Milliken praised Synanon while also hinting at its future downfall. Milliken, who served a 14-year tenure as Michigan's longest-serving governor, was a frequent visitor and advocate of Synanon and other rehabilitative drug and alcohol programs.

"Synanon has provided rehabilitation and hope for significant numbers of drug users," Milliken said. "We have had a Synanon facility in Detroit for some five years now, and that facility almost had to close its doors last month because it could not raise $40,000 for operating expenses. Synanon may yet close in Detroit if a permanent facility and permanent funding cannot be secured for its work."

Detroit Synanon members

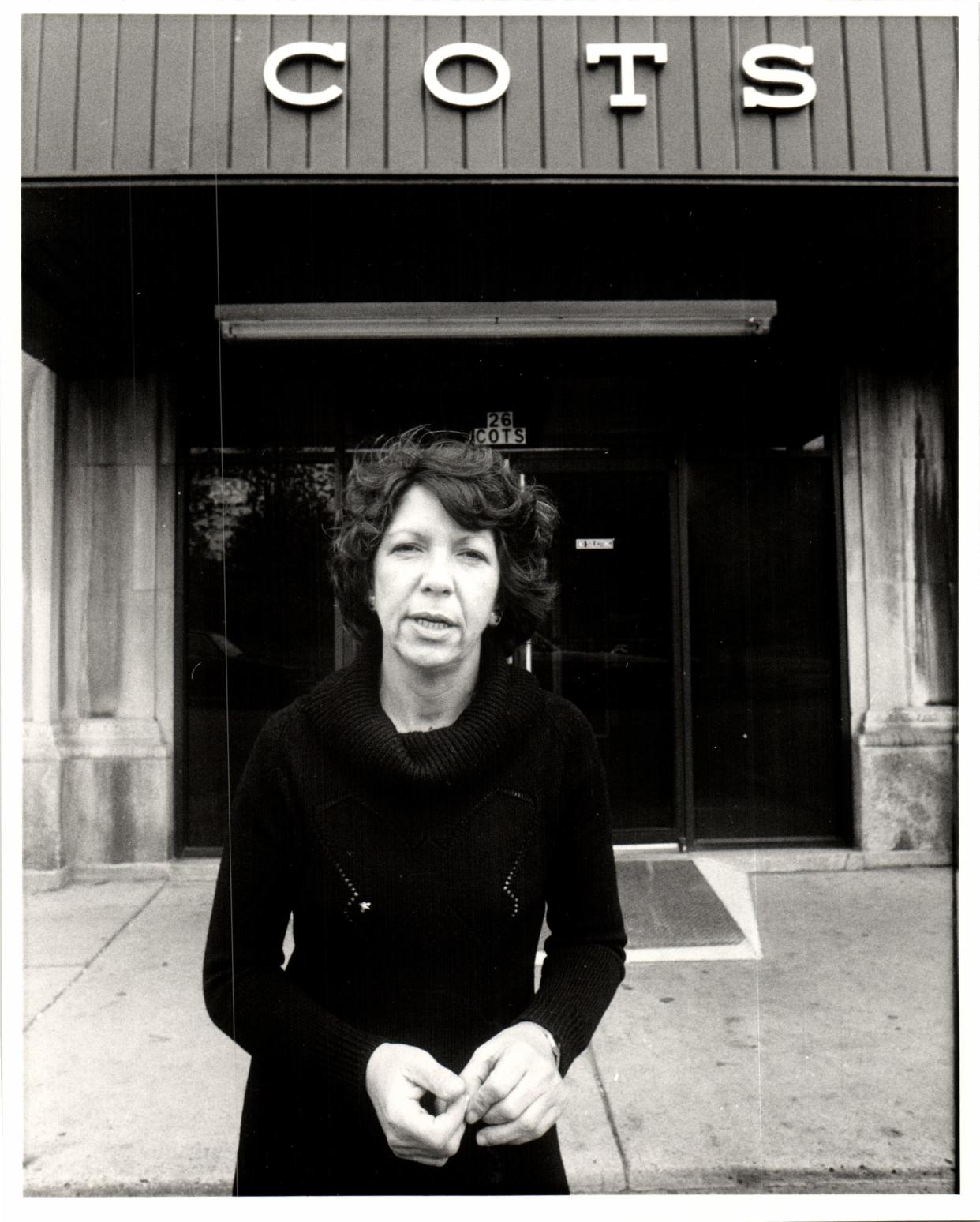

Before becoming Executive Director of Detroit's Coalition for Temporary Shelter in 1982, Jarrie Tent served as Synanon's director of education, according to a biography published in the Detroit Free Press in 1984.

In an online forum dedicated to testimonials of former Synanon members, Michigander Cynthia Manuel explained how she fell into the group while a student at Wayne State University in 1968.

Manuel was a member of Synanon for eight years, ultimately moving to Santa Monica, California, with her husband, John Frazer, (whom she met in the group), and their daughter, Morgan.

Manuel posted a letter she wrote her friend Laura on Feb. 25, 1976, where she explained the latest Synanon requirements, including vasectomies, abortions and divorces.

"Since I last wrote, I plotted to 'escape' several times," Manuel wrote in the letter titled 'Confused Letter #2.' "Written in red letters on your conscience is the idea that after all Synanon has done for you — you must not only be eternally grateful and humble, but you must pay back with service."

With the help of her sister, Manuel wrote that she left Synanon on March 5, 1976, with her daughter and reestablished their home in Michigan.

"The adjustment to life outside the cult was akin to returning to Earth from another planet. I was a stranger in a strange land and no one could understand where I had been or what I had experienced," Manuel wrote in her online testimonial. "I mourned my lost community."

More: 6 who went missing in Missouri may be tied to a cult. Here's how social media draws people in.

In HBO's "The Synanon Fix," Mike Gimbel details the story of his time in Synanon, which began with a marriage to Detroiter Stephanie Andreucci. Andreucci would move to Santa Monica, California, with Gimbel to be Synanon's top chef.

"We were around each other all the time. We had built a really good friendship, and we were really, really close," Gimbel said in the docuseries. "We were doing the lunch, cleaning up ... and Chuck (Dederich) said, 'You know, the two of you are very good for Synanon.' Three days later, we were married."

Andreucci would stay with Gimbel until the late 1970s when Diederich's "changing partners" rule was instated, she was reassigned to top Synanon member Lance Kenton, son of jazz player Stan Kenton.

Kenton would later take responsibility for helping to place the rattlesnake in Morantz's mailbox and go on to serve 80 days in prison — although in an interview for "The Synanon Fix," he would not admit whether he had any real involvement.

Detroit-born jazz player Wendell Harrison said he spent time at Synanon's Santa Monica location from 1967-69. In a 2011 interview with the Detroit Free Press, Harrison said his time dedicated to sobriety at Synanon was a pivotal moment in his life story.

"It boosted my confidence and gave me a sense of direction," he said. "Before then I was a flake. The hardships you go through give you conviction. My knowledge comes from experience."

[Stream "The Synanon Fix" on HBO Max at www.max.com]

Did you or a family member spend time at Detroit's Synanon House? Email us your story at city@freepress.com and we'll include it.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: 'The Synanon Fix' documentary on HBO Max shows drug rehab turned cult