How documentary 'Beyond Utopia' obtained shocking footage from inside North Korea

Madeleine Gavin, like many readers, was haunted by the story of Hyeonseo Lee, a woman who fled North Korea with her family in the 1990s and documented their perilous journey in her bestselling 2016 memoir The Girl With Seven Names.

But it also sent the documentarian down a months-long wormhole of dark-web research on the country and its notoriously oppressive living conditions under the dictatorship of Kim Jong Un. She used different VPNs (virtual private networks, which allow users to mask their IP data and avoid firewalls and other blockers) and searched in multiple languages.

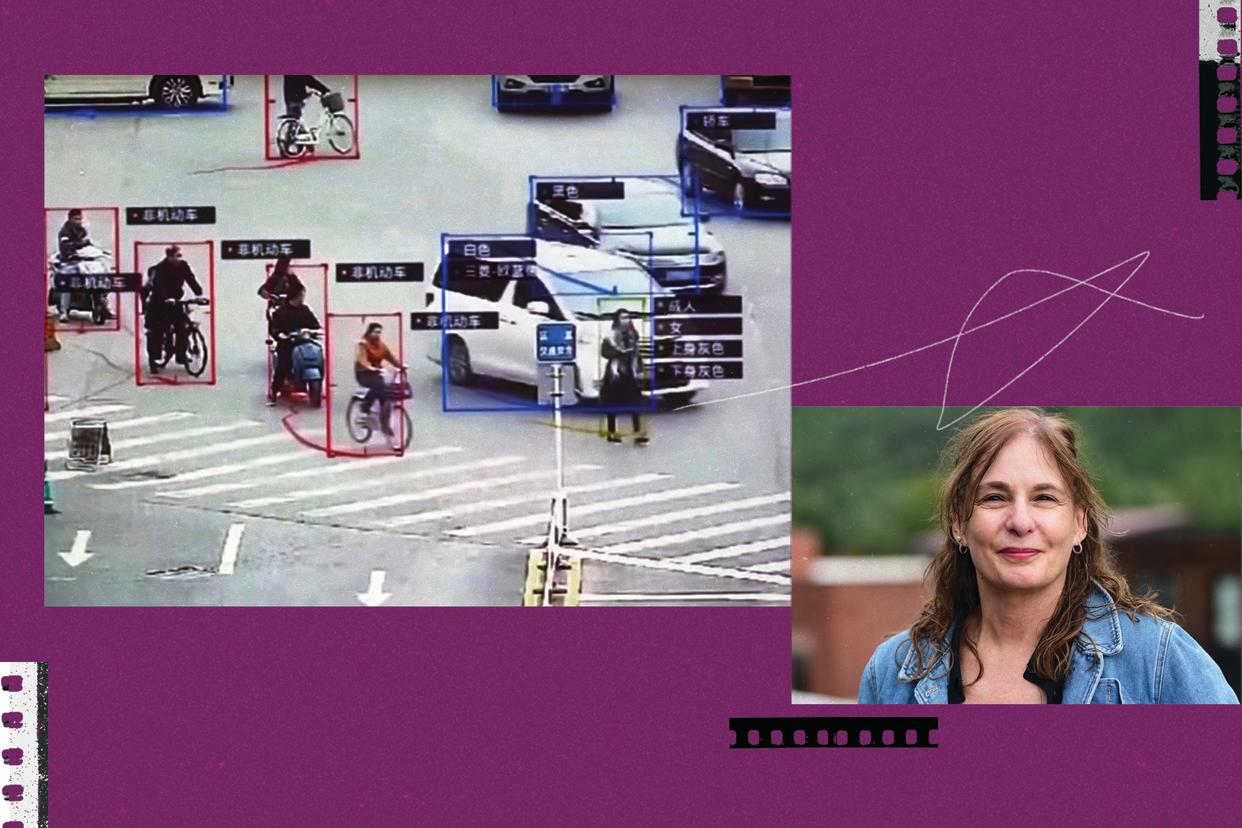

“And depending on which country I searched from,” she tells Yahoo Entertainment in a new interview, “I was finding different little pieces of not only crazy propaganda out of North Korea, but also this incredible hidden camera footage that these very determined and extremely brave North Koreans were risking their lives to shoot of what real life was like inside North Korea.”

That’s when Beyond Utopia, Gavin’s stunning Sundance-winning documentary, which not only features much of the shocking footage she found online but also follows the harrowing escapes of other defectors from the nation, was born.

“On our news, we basically see what the Kim regime would like us to see, which is the missiles and the parades,” explains Gavin, who previously explored oppressive conditions for Congolese women in the 2016 documentary City of Joy. “And so when I started to see that footage and feel the pulse of the people, I was like, ‘This movie has to be made because there are 26 million people living inside North Korea, and we have largely ignored them for the last 70-plus years.’”

The footage shows North Koreans living in fear and squalor (even forced to collect their own feces to turn over to the government for fertilizer), children marching out of school to watch public executions, teens and adults being brutally beaten and sent to labor camps for life or even executed for “crimes” as simple as watching South Korean media or speaking ill of the regime. Kids are taught, however, that their life is idyllic and that Kim is almost a Christlike figure, while the United States is the epitome of evil. As revealed in the film, North Koreans don’t use the word “Americans”; it’s exclusively “American bastards.”

Beyond the hidden camera video that Gavin unearths, she and her team also follow two escapees, including the harrowing journey of a mother, father, two young children and elder grandmother.

Leaving North Korea is not as simple as climbing a fence — or even surviving the trek across the currents and cold of the river that separates the country from China. Because the regime has cozy relationships with neighboring nations China, Laos and Vietnam (where hunting and capturing defectors is a profitable business in which people caught are often sold into human-trafficking), escapees must journey on a secret underground railroad through all three nations before hopefully finding refuge in Thailand and ultimately landing in South Korea.

“China is really the worst,” Gavin says. “China is so complicit with North Korea, and they have a policy that has only gotten worse over the last few years of repatriating any North Koreans who they find within the walls of China. There are a lot of North Korean women who make it over the river from North Korea into China, but then don't know how to get through China. … And a lot of these women are sold into marriage in China. And they’re sold into sex-trafficking.

“It’s a little bit catch-as-catch-can in Laos or Vietnam. There are times when North Koreans who are caught in those countries are repatriated to North Korea, and there are other times when they might be put in prison and then eventually let go. So those are not as definitive, but they are also not friendly to defectors.”

Beyond Utopia’s hero, meanwhile, is the man orchestrating many of these treacherous flights to freedom: Sung-eun Kim, a South Korean pastor who has helped more than 1,000 North Koreans defect over the past decade — and who once broke his neck helping some cross a river on the border of China and fell off a cliff in Laos.

“Pastor Kim is first and foremost a pastor, and he made a commitment to his God 23 years ago that he would devote his life to this,” Gavin says. “That he would not only devote his life to this, but that he would go along the journeys with the people he was trying to help escape. … He has had multiple surgeries on various parts of his body. He is in constant pain. He doesn’t go to China anymore because he was warned that he could be kidnapped into North Korea. But he is afraid for his life in all of these countries because Laos and Vietnam, also Cambodia, have relationships with North Korea. But this is the commitment he made, and he’s followed through on it. And as terrified as he is, he feels like he has to keep going.”

So does Gavin, who made Beyond Utopia despite the upheaval that followed the release of the 2014 Seth Rogen-James Franco comedy The Interview, as a cybercrime group purportedly linked to North Korea’s regime hacked into its distributor Sony’s emails and made public embarrassing messages, while also threatening an attack against the film’s premiere.

“This has been something we’ve been obviously talking about from the very beginning,” says Gavin when asked if she’s worried about her own security. “And we were very concerned in some ways. But knocking on wood here, the more we learned, the less concern we [had]. We have a vast group of consultants on this film that are in the policy world in South Korea and the United States. ... And everybody seems to think that with The Interview, Kim Jong Un was brutally mocked. He was humiliated in that film and that drove him mad. And in terms of our film, I mean, first off, our film is really about the people. North Korea and the Kim regime are important parts of our film because they are the backdrop. They are the reason that people need to escape and want to escape and have to escape. So we had to give information on Kim Jong Un and on the Kim regime. But what we say about Kim Jong Un, by all accounts in our research and the vetting that's gone on, we say that he’s a brutal dictator. He is a strongman. These are things that are said on the news all the time. And Kim Jong Un, by all accounts, isn’t really that bothered by that. I don’t want to tempt fate, but the Kim regime has known about our film for almost a year now. I’m sure that they have seen it.

“But at a certain point, I think in the making of this film, we felt like we were in so deep with everybody, and the film and what we were trying to do felt so necessary and important there was no turning back. So we had to face those fears and kind of drive through them because there was no other way to make a movie like this.”

Gavin has a simple message for what she hopes people take from the film, which will likely be in contention for Best Documentary at March’s Academy Awards ceremony.

“What I hope is that when we talk about North Korea, every country, every news organization, they talk about the people every single time. We can talk about the missiles. And that’s fine. North Korea will never give up their missiles. Because they know that they will not exist as a country if they give up their missiles. But we have to be talking about the people, because there’s going to be a current of energy that can affect Chinese policy, and that can affect North Korea if we do that.

“The other thing is the exchange of information is so important. Getting the truth of North Korea out, which is that footage that I discovered. … [But also] getting information about the outside world into North Korea, because we need North Koreans to know that they deserve more. If you’re North Korean, unless you live right on the border of China, if you’re inland, you don’t know anything about the outside world. There’s no internet. There’s no cell service inside the walls of North Korea, other than little pockets along the river where you might get a cell signal. And those people are being told that, yes, their lives are hard, but that their life is far better than anywhere else in the world. And so getting information about the truth of the outside world in so that North Koreans can start to realize, wait, we deserve more. That exchange of information is huge. And so our film is pushing for that. And then, like I said, we’ve got to be talking about the people. There are 26 million people and they have been suffering for more than 70 years. And it's outrageous that we don't advocate for them every chance that we can.”

Beyond Utopia is now streaming.