Disability rights groups are fighting for abortion access — and against ableism

The conversation about abortion and other reproductive health care in the country is missing something: people with disabilities.

Since it became clear the Supreme Court would overturn Roe v. Wade, disability rights advocates say the uproar over allowing states to ban or restrict abortion has largely overlooked the ways people with disabilities will suffer. At least 12.7% of the U.S. population lives with disabilities — including from speech and limb differences, mobile disabilities and developmental disabilities — as of 2019, according to census data.

“I think one of the reasons that disabled people are not centered in these conversations, even though we should be, is that typically disabled people are de-sexualized,” said Maria Town, president and CEO of the American Association of People With Disabilities (AAPD). “We are not seen as sexual beings. In fact, the assumption is that we just don’t have sex when, in reality, disabled people do have sex. We need and deserve accessible, affordable reproductive and informed reproductive health care, and that includes abortion.”

Even after years of highlighting the longstanding lack of access to reproductive care, people with disabilities are still less likely to have health care providers and routine check-ups, and are more likely to have unmet health care needs because of the cost, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Access to reproductive services is even slimmer.

“You may need an additional support person for physical access or to provide mental health support,” said Town, who has cerebral palsy and uses mobility devices. “For states that have banned abortion and people are talking about needing to travel out of state or use telehealth services, many telehealth platforms are not accessible to people with disabilities. These are all barriers to health care. Accessibility of reproductive health care can be a huge challenge.”

People with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty than those without and often rely on state insurance programs like Medicaid to meet health care needs, according to the

DC Abortion Fund, a nonprofit group that helps low-income people pay for abortions. However, only 15 states and Washington, D.C., cover abortions through Medicaid, a significant financial barrier to abortion access for people with disabilities.

For example, West Virginia, which has the largest population of disabled people in the country, according to census data, solely provides state funds for abortions in cases of life endangerment and fetal impairment. An analysis by the National Partnership for Women and Families found that abortion bans in the 26 states that are certain or likely to ban abortion could affect up to 2.8 million women with disabilities (53 percent of all such women in the U.S.).

Since the Supreme Court’s ruling, disability rights groups like the AAPD and the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund have condemned the Supreme Court’s action, detailing the myriad ways people with disabilities will be affected by the decision and calling out ableism in the national conversation about reproductive justice. Black people bear the brunt of this injustice. About 1 in 4 Black adults in the country have a disability, compared with 1 in 5 white Americans, according to the CDC. And about 36% of Black people with disabilities live in poverty, compared with 26% of America’s overall disabled population.

“Abortion advocates need to stop saying that the main reason to want abortion is to not have a disabled child,” disability rights advocate Imani Barbarin said. “There’s nothing like entering a space and the only reason they want access to this medical procedure is to not have somebody like you in their life. This is turning away tons of pro-abortion advocates who have disabilities.”

People with disabilities across the country have reported experiences with health care providers that left them feeling discriminated against and concerned about the quality of care they’d receive. In a study by the National Research Center for Parents with Disabilities, one doctor jokingly asked a woman with a physical disability if she “used a turkey baster” to get pregnant, another refused to touch a pregnant woman’s amputated leg to help her push during labor, and one nurse remarked to another woman that “it was wonderful that somebody like [her] would still want to have a kid.”

And the marginalized group fares no better when it comes to terminating a pregnancy. A New York woman recently told The New York Times that Planned Parenthood of Greater New York canceled her abortion appointment, telling her, “We don’t do procedures for people in a wheelchair.” (Planned Parenthood officials later apologized and said the woman’s appointment had been “mismanaged.”)

But the challenges of reproductive care don’t start at pregnancy, Town said people with disabilities experience unfair treatment from the time they are young.

“Procedures like pap smears are not inherently accessible to me,” Town said. “In the broader reproductive health care space, many disabled people are sterilized forcibly. And if they’re not sterilized, they’re placed on birth control or other forms of contraception without their consent. That happened to me as a young girl. Not for any health-related reasons, but so I was easier to care for.”

Stefanie Lyn Kaufman-Mthimkhulu, founder of the disability rights grassroots organization Project LETS, who is nonbinary and uses they and she pronouns, said they had an abortion in 2020 months after giving birth to a daughter. Kaufman-Mthimkhulu has Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS), a rare neuromuscular disorder that results in muscle weakness and several other symptoms like trouble walking, speaking and breathing. Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said they sometimes use a wheelchair. They also have autism and endure chronic pain in their ankle and spine as a result of multiple surgeries, they said.

As a result, their body had “negative reactions” to being pregnant and their pregnancy was labeled high risk as a result of their disabilities — “Pregnancy exacerbated my current pain and health issues, and created new issues. I was constantly in severe pain, and former tools like medical marijuana were no longer accessible to me,” Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said.

Research shows that people with disabilities get pregnant at similar rates to those without, but are more likely to experience blood clotting, hemorrhaging and infection during pregnancy, according to research published in the Disability and Health Journal. They also often receive inadequate health care and are at significantly higher risk of dying from pregnancy and childbirth, the research showed.

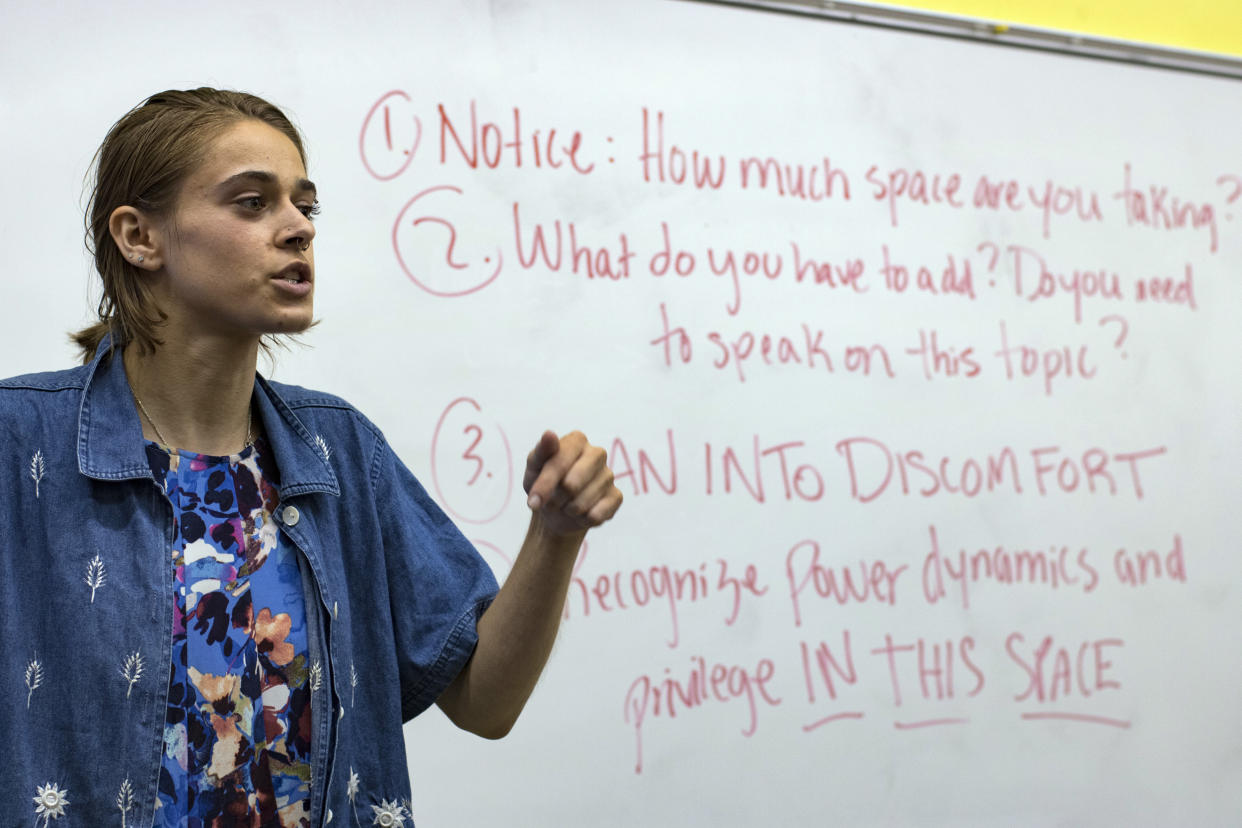

Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said in the wake of Roe being overturnedruling, Project LETS is working to develop political education sessions to both teach the public about the connection between reproductive and disability rights and strengthen mutual aid networks to support people with disabilities who need access to abortion, medication and other reproductive necessities. She said one key to fighting back against abortion restrictions for people with disabilities will be to strengthen systems that allow people with disabilities to give birth outside of traditional medical environments.

For instance, the organization is working with doulas and birth workers to create care networks for people outside of the traditional health care system, she said. This is important as people with disabilities navigate a system that doesn’t always tend to their needs. “Pregnancy put my physical body through hell, and mental, spiritual and emotional stability was significantly destabilized — to a point that I don’t believe has recovered.”

But harshly restricted access to care won’t be the only consequence of overturning Roe. Barbarin said organizations must prioritize making sure people with disabilities have access to their necessary medications moving forward.

“So many disabled people’s medications have ended because they’re abortifacients,” Barbarin said, referring to substances that induce abortion. “So people who are on certain lupus and cancer drugs have had them stopped immediately.”

One example of this is the drug Methotrexate, which is used to treat several types of cancer — like leukemia and lymphoma — and various diseases like lupus and Crohn’s disease. It is also an abortifacient, often used to treat ectopic pregnancies. The Lupus Foundation of America this month acknowledged reports of people having trouble accessing the drug since the Supreme Court ruling.

“We need not just people who are reproductive advocates, we need people who are medical advocates for people with disabilities. I really want people to understand that, if you want to talk about intersectionality, you need to get disabled people their meds.”

Barbarin, Town and Kaufman-Mthimkhulu agree that proper sex education is necessary for a future where people with disabilities have unlimited access to reproductive care. Up to 36 states don’t include the needs and challenges of youth with disabilities in their sex education requirements or provide resources for accessible sex education, according to a 2021 report from the nonprofit Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. And of those that do, only three explicitly include the group in their sex education mandates.

As the nation gears up for life without federal abortion protection, disability rights groups are prioritizing community care, medication and education for people with disabilities. Even with all these efforts, they say, it’s important to move away from ableist rhetoric that only further marginalizes people with disabilities.

“Often times, disabled folks are used as scapegoats for pro-life arguments. Like, ‘Look at all of these babies labeled with prenatal abnormalities that are aborted!’” Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said.

“While it’s true that we must interrogate the ableism that leads to many disabled fetuses being aborted, disabled folks are not to be used as props to support harmful pro-life policies. We are not your pro-life scapegoats, and eugenics has no place in abortion access.”