Digital evidence is reshaping police work. How a new unit is cracking cases in Providence.

PROVIDENCE – Someone's bullets had killed a couple in the Elmwood neighborhood. Brian Fernandez and Sreylakh Ros were parents, whose children included toddler-age twins.

The Providence police detectives on the double-homicide case knew their bosses would want an answer to a specific question. In fact, it was often their commanders' first question.

Do you have any cellphones or video yet?

None of this was new; cellphones and video cameras have always been a source of valuable digital evidence.

But this time, in late October, the city's homicide investigators had a new and improved capability to help them tackle the job, say police. A change instituted last March had created a new three-person team within the detective bureau.

Cellphone data is the 'modern-day DNA'

The digital intelligence unit, as it's known, is on the third floor just down the hallway from the commander of the city's detective operations, Detective Maj. David Lapatin.

The unit is led by Detective Sgt. Jonathan Primiano, a 22-year veteran of the force.

Primiano's office is adjacent to a slightly bigger room where Detectives Mitch Guerra and Joseph Nezier were working at two terminals on a recent afternoon.

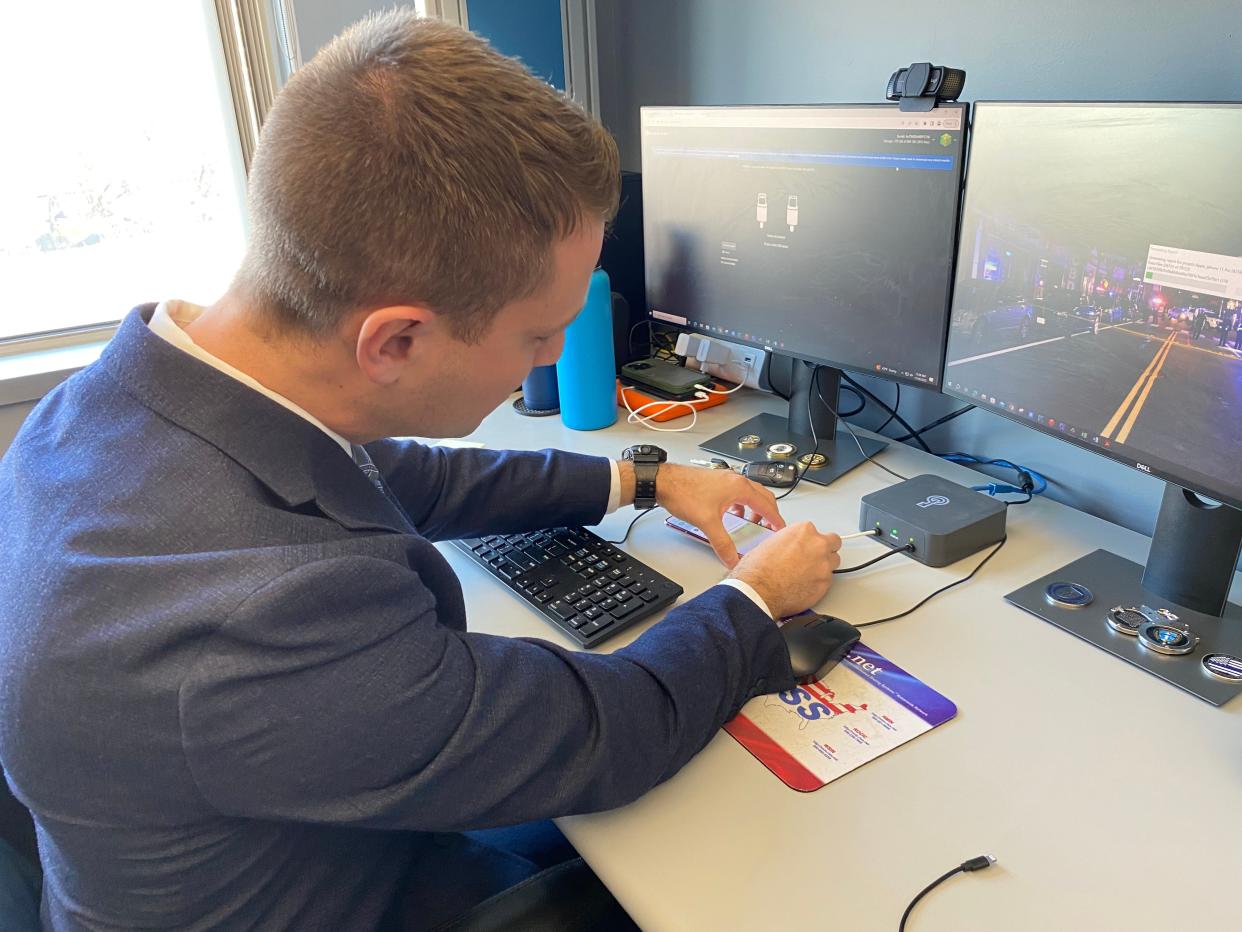

A collection of cellphones, more than 20, are charging in a large station. Guerra grabs one and plugs it into a short Lightning-style connector that runs into a box resting on the desk just beneath the monitor.

A marking on top of the box identifies it as a piece of equipment that was part of a system known as GrayKey when it first came out.

"Meet GrayKey …" says the presentation posted on YouTube. "GrayKey gives you access to the latest iOS and Android devices, often within an hour. So you can solve more cases faster. In a criminal investigation, every second matters. GrayKey is designed to help you secure evidence, swiftly investigate crime and ensure public safety."

Guerra says he and Nezier typically lean on GrayKey to help them get them through passcode protections on phones that investigators have seized for evidence.

"Everything you do in your phone, that's your identity now," says Primiano. "That's the modern-day DNA."

Pioneering police tactics: From wildfires to standoffs, UAVs are transforming RI policing

This means phones are full of information of value to investigators, from videos to text messages to location data. If someone has committed a crime, their phone might hold evidence. The phone of a slain person can hold evidence, too.

"One way or another," Primiano said, "we're going to find you in that phone."

Nezier is sitting at a terminal he says he and Guerra tend to rely on after they've gained access to a device. At that point, the job is extracting and analyzing valuable data.

The terminal is operating software provided by Cellebrite, an Israeli company that supplies tools to police agencies all over the country.

"There's an explosion in digital evidence and it's transforming public safety and private enterprises," says a post on Cellebrite's website, which also says the company's "singular focus is to help agencies solve every case and complete every mission."

"We do it to create safer communities," says the post. "We do it to create a safer world, to help victims and their families find justice, reclaim their lives and protect the innocent."

"We constantly innovate because those protecting our communities deserve the most advanced technologies to solve cases and complete missions," it says, "allowing society to flourish."

Not long after Guerra plugged in the cellphone, a chime rang out in the unit. GrayKey had identified the phone's passcode.

Police: 'We're not fishing'

Guerra, Nezier and Primiano have an array of other tools they use to develop what their supervisors refer to as "actionable digital intelligence."

Basically, that's information that constitutes evidence or might lead to evidence that solves crimes. The detectives' work challenges their skills across the digital realm, from social media and other online content to content stored on computer hard drives, video recorded by surveillance cams, other types of digital imagery, financial transaction data and tracking data on cellphones.

Valuable tools for investigating crimes are frequently controversial.

Primiano emphasizes that the team is not trawling for large volumes of data for future use.

"We don't fish," he says. "We're not fishing."

They target certain data because they believe it might help them solve crimes, he says, adding that they comply with the Fourth Amendment. The language in the U.S. Constitution protects citizens from unlawful search and seizure.

Deviating from that presents risks, Primiano says.

"We're all going to testify in court on these things," he says. "You're only as good as your reputation when you take the stand in court and testify," Primiano says.

New unit focuses exclusively on digital evidence

The use of such tools is not new in Providence, or in Rhode Island for that matter.

What is new for the Providence detectives, however, is the setup.

Since last March, Guerra and Nezier have been able to focus on matters of digital intelligence. The unit shelters them from certain other jobs carried out by detectives working in a more traditional rotation.

Don't make a peep: Noise detection cameras coming to Newport. How they work.

Detectives outside the unit can have skill with phones and video. But they have other responsibilities, too.

In a previous era that Lapatin experienced, back when digital intelligence was not as rich, detectives and their commanders focused on more traditional types of evidence, such as witness statements or analysis of crime scene evidence such as fingerprints, blood and tire tracks.

Lapatin said he has wanted a dedicated unit within the bureau for at least 10 years. An opportunity to follow through came last spring after the appointment of Providence police Chief Oscar L. Perez Jr., Lapatin said.

"Under Chief Perez we were able to do that pretty quick and get rolling," he said.

Wide variety of digital evidence requires specialized training

James Emerson chairs a committee on digital evidence and computer crimes that reports to the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

In the current era, the amount of digital evidence that's available for potential crime-solving and prosecution is so voluminous that many law enforcement organizations are struggling to make use of it, says Emerson, a vice president at the National White Collar Crime Center.

Exploiting this vast landscape of evidence takes technological expertise, Emerson says.

Legal ability can come into play, too, as state legislatures pass laws that limit investigators' access to particular types of digital evidence, he says.

The job of collecting that evidence and successfully presenting it in court is easily underestimated, Emerson says.

Such work involves a deep understanding of the underlying structure that supports digital files on a computer or a device, he says.

It also entails an ability to find digital evidence and provide exhibits of that evidence without contaminating it.

Developing competency in these areas takes time, and retaining that competency takes continuous learning, Emerson says.

For example, encryption evolves along with responses to encryption.

For these reasons, a setup that allows two detectives and a sergeant to focus on such work "absolutely" strengthens the department's capability, Emerson says.

Payoff of the new unit: Speedier investigations

Speed is one of the visible and immediate benefits of the new arrangement, according to Primiano, who says the department is benefiting from digital intelligence work that is happening more quickly in certain situations.

Apparently, that speed provided an advantage as homicide detectives arrived at the scene on Hathaway Street, off Elmwood Avenue, where Fernandez, 29, and Ros, 30, had been fatally shot as they sat in a vehicle, police say.

The investigation began just after midnight on Oct. 28.

In less than 24 hours, investigators had secured a cellphone that held key information, says Providence police Detective Lt. Dennis O'Brien. In less than 30 hours, he says, they had accessed that digital information.

And on Nov. 9, Lapatin and Perez announced the arrest of two men in the double homicide. They pointed out that the new unit had been key.

O'Brien and Primiano aren't willing to tell the story in detail.

"But the tools and technology they were able to use were absolutely crucial to the case," says O'Brien.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Digital detectives speed up crimefighting in Providence, police say