Supreme Court decision leaves family of a man killed at the border searching for justice

TOHONO O’ODHAM NATION, Ariz. — It was a dark and chaotic scene in the Arizona desert the night 58-year-old Raymond Mattia died from nine bullet wounds after three Border Patrol agents fired dozens of rounds at him.

Brandishing flashlights and handguns, 10 Border Patrol agents were responding to a call that shots had been fired about a mile from the U.S.-Mexico border. As they walked through patches of cacti, Mattia stood shrouded in darkness steps from his home holding something in his hands.

“Put it down for me. Put it down,” one of the agents shouted, according to shaky bodycam footage of the incident.

The Untouchables: NBC News investigates how federal law enforcement officials are able to harm people with little to no accountability.

Mattia complied, tossing a sheathed machete to the ground.

“Put your hands out of your f------ pocket.”

Mattia fumbled with the pocket of his green jacket. He appeared to toss an object aside.

Almost simultaneously, three agents opened fire. Less than 30 seconds after the agents first spoke to him, Mattia slumped to the ground. A cellphone, not a firearm, lay on the ground.

His sister Annette Mattia, 61, was just yards away in her own house the night of May 18. Five months later, she choked down tears while standing near the spot where he lay.

“This is where he lived, and it just is sadness and anger because it didn’t have to happen at all,” she said. “If they would have talked to him it would have turned out a lot different because you know he wasn’t a threat.”

“He didn’t deserve to die like this,” her daughter Yvonne Nevarez, 43, added.

Now, the family wants justice.

“To me it feels like there are still murderers walking around. Who knows they might be back out here again? Who knows what they might do to anyone else?” Annette Mattia said in an interview outside her home.

The family, several of whom live on a compound in Menagers Dam Village within the Tohono O’odham Nation, believe that the agents ruthlessly gunned a man down with scant regard for his constitutional rights. But federal prosecutors have already said there will be no criminal charges.

A recent Supreme Court ruling means any effort to sue the agents individually for alleged constitutional violations is doomed to fail. The 2022 ruling is one in a line of cases that has decimated the ability of victims to file lawsuits, known as “Bivens claims,” accusing Border Patrol agents of using excessive force or other constitutional violations.

The court's dismantling of Bivens has reverberated throughout the federal government and touched nearly every agency, but Border Patrol represents a large fraction of armed federal law enforcement NBC News found that the ruling has also made it more difficult to sue agents in other federal law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, U.S. Marshals Service, Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

The geography of the Border Patrol’s jurisdiction presents a uniquely thorny set of legal questions.

The court, in a case called Egbert v. Boule that involved a claim against a Border Patrol agent, introduced a new legal test that makes it virtually impossible to bring a wide range of claims against federal officials.

And so the Mattia family is far from alone.

In the aftermath of the ruling, lawsuits alleging a wide range of constitutional violations are now routinely tossed out. People mistreated by federal officials aren’t getting their day in court, instead being denied the chance to find out if a jury would agree that their constitutional rights were violated. The court has also made it harder to sue government officials by continually strengthening the legal defense known as qualified immunity — a point that drew the direct ire of protesters during the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd.

In the 12 months after Egbert, lower courts cited it 228 times in a range of cases against all kinds of federal officials, according to an NBC News search using the LexisNexis legal database. In 195 of those cases, constitutional claims were dismissed.

Also in the year after the Egbert ruling, judges tossed more than a dozen lawsuits in which Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which Border Patrol is part of, or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers were defendants accused of violating constitutional rights.

Among the 15 out of 16 claims dismissed:

Migrants affected by the Trump administration’s policy of separating children from parents when detaining people at the border.

A protester in Texas who claimed that Border Patrol agents had unlawfully arrested him and used excessive force by pushing him to the ground and punching him.

A Mexican national on vacation in New York who was shot in the hand and face by an ICE agent during an incident in which someone else was being sought.

A Mexican immigrant who initially ran from ICE agents but stopped and, he says, held up his hands before being shot in the arm.

Even when a federal employee at the Department of Homeland Security sued officials in the department for malicious prosecution after being accused of falsifying documents, a judge dismissed the claim partly on the grounds that, in line with Egbert, “regulating the conduct of immigration agents similarly risks judicial intrusion into national security.”

Some plaintiffs gave up in light of the Egbert decision. Abdulkadir Nur, a Somali American Muslim, who said he was harassed by border protection agents at the airport every time he entered the country, withdrew his Bivens claim after the ruling was issued.

“It’s been predictably a nightmare. We have had to voluntarily dismiss Bivens claims in most of our cases,” said Justin Sadowsky, a lawyer with the legal arm of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, which represents Nur.

The message to federal officers accused of misdeeds is clear: You won’t face lawsuits for your actions.

Without individual accountability, wrongdoers are protected and unconstitutional practices can quickly become normalized among sprawling federal agencies like the Border Patrol, civil rights advocates say.

The plight facing Mattia’s family puts the spotlight on how the Supreme Court ruling affects the U.S.-Mexico border, an area many already view as a lawless hinterland where constitutional rights are not respected.

“The court’s opinion in Egbert is unequivocal that there is no damages action available against any Border Patrol agent for any reason,” including over what happened to Mattia, said Patrick Jaicomo, a lawyer with the libertarian-leaning Institute for Justice.

Lawyers for the Mattia family plan to pursue a wrongful death claim against the federal government, with an announcement scheduled for Friday, the details of which were exclusively shared with NBC News. And while the lawyers say they are not yet completely ruling out bringing a lawsuit alleging constitutional violations against the officers themselves, they concede that they would be facing extremely long odds.

“It makes it very, very difficult to hold the individual officers accountable in front of a jury,” lawyer Timothy Scott said of the Egbert ruling.

‘Absolutely immunized’

Mattia groaned motionless on the ground.

“Hey, do not f------ move,” one agent said.

The agents handcuffed him, blood soaking through his jacket.

“Where’s the firearm?” an agent asked.

Another tended to his wounds: “Keep breathing, bro,” he said.

The agents encountered Mattia at 9:39 p.m. He was pronounced dead at 10:06 p.m.

Whether the officers were looking for Mattia that night, or knew him before, remains unclear. His story is complicated. A toxicology report indicated he had alcohol, methamphetamine and oxycodone in his system at the time of death. He had a criminal record that included a conviction for a sex offense decades ago.

For Annette Mattia, learning about the recent Supreme Court ruling feels like insult added to injury after what happened to her brother.

“They know they’re going to get away with it,” she said. “We’re not going to get justice.”

The idea of suing government officials for constitutional violations is not a new one.

In fact, the 1871 Civil Rights Act passed after the Civil War specifically allowed such claims against state and local officials.

But there was a glaring omission. The law said nothing about federal officials.

A hundred years later, in Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, the Supreme Court ruled that federal officials could also be sued on similar lines. These became known as “Bivens” claims after Webster Bivens, who filed the original lawsuit seeking damages when federal agents raided his Brooklyn apartment, without a warrant, looking for drugs.

But over the following decades the court then slowly unraveled that decision.

In the recent Egbert case, the court ruled 6-3 that individual Border Patrol agents generally cannot be sued for constitutional violations.

Conservative Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the majority, cited national security risks as a reason not to allow suits against Border Patrol agents. The court ruled that a bed-and-breakfast owner near the U.S.-Canada border in Washington state could not sue an agent for excessive force following an altercation on his property.

Thomas said that the court is “comparatively ill-suited to decide whether a damages remedy against any Border Patrol agent is appropriate.”

The ruling prompted a fierce dissenting opinion from liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

“Absent intervention by Congress, CBP agents are now absolutely immunized from liability in any Bivens action for damages, no matter how egregious the misconduct or resultant injury,” she wrote.

Although the ruling did not purport to overturn Bivens outright, many legal experts think that it did so in all but name, a view shared by conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch. “I would only take the next step and acknowledge explicitly what the court leaves barely implicit,” he wrote in a concurring opinion. It would only be fair to future litigants to “not hold out that kind of false hope,” he added.

In theory, claims addressing a small subsection of constitutional violations previously approved by the Supreme Court, such as excessive force claims against federal agents who conduct warrantless raids similar to the one in the original Bivens case, could still go forward. But even those cases are now in question.

The decision was the second in two years in favor of Border Patrol agents, the first being Hernandez v. Mesa in 2020, which concluded that Bivens claims could not be made for incidents in which agents shoot someone on the other side of the border.

The Supreme Court’s stance on Bivens has infuriated a cross-ideological alliance of lawyers, with both liberal and libertarians critical of its willingness to shield federal officials.

“What the Supreme Court has been doing with Bivens is essentially giving federal agents absolute immunity for constitutional violations. That’s the endpoint to which they are marching,” said Portland-based civil rights lawyer Athul Acharya.

Some members of Congress have backed legislation that would allow for constitutional claims to be brought against federal officials.

Rep. Hank Johnson, D-Ga., who has co-sponsored legislation to codify Bivens, said in an interview that he plans to re-introduce a bill soon.

“It stands to reason that federal officials should not be exempt from being held accountable by the very people that they serve. If it’s good enough for state and local officials, it should be good enough for federal officials,” he said.

‘A nightmare’

For those living in the desert reservation community of Menagers Dam Village, a cluster of one-story dwellings a two-and-a-half hour drive from Tucson, the normal rhythm of life is regularly disrupted by the unique circumstances of living a 15-minute walk from the border.

The Tohono O’odham Nation, which has about 28,000 members, straddles the border, with some historic lands sitting on the Mexican side. The name of the tribe translates from the O’odham language as “people of the desert.”

Border Patrol agents, often the focus of complaints from immigration rights advocates for heavy-handed tactics, regularly motor around in trucks and SUVs, stopping locals to ask questions. From their living room windows, residents can watch the end of the 2,500-mile journey migrants make to illegally cross the border, sometimes late at night as they walk through the village.

Members of the tribe, including the Mattia family, have a mixed relationship with the agents, grateful for their efforts combating the trafficking of people and drugs, but sometimes irked by the constant presence of federal law enforcement officers on their land.

“It’s people on both sides of the border who are dealing with Border Patrol and their lack of respect for people, their lack of respect for life,” said Yvonne Nevarez, Annette Mattia’s daughter.

It was the tribe’s police department that called in the Border Patrol to assist on the night of the shooting, a decision that Mattia’s family has also questioned. The dispatcher relayed a report of shots fired near Mattia’s house.

“The police officer and agents encountered an individual outside of a residence who threw an object toward the officers and abruptly extended his right arm away from his body. Three agents fired their service weapons, striking the individual several times,” a Border Patrol statement on the shooting said. A spokesman declined to comment further.

The Supreme Court’s retrenchment on Bivens has occurred at the same time that the number of federal law enforcement agents has dramatically increased, especially within DHS, a sprawling department created in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and which includes both CBP and ICE. In 2019, the Justice Department said there were about 132,000 federal law enforcement officers in total.

In 1992, there were just over 4,000 Border Patrol agents, about a fifth of the current number, according to the agency.

Despite being one of the largest law enforcement agencies in the nation, “Border Patrol has been given a hall pass for constitutional violations,” said Mitra Ebadolahi, a former American Civil Liberties Union lawyer who has worked on border issues.

'Pale substitute'

Annette Mattia saw the border patrol agents moving toward her brother’s house by the side of her property. She called him on the phone and told him they were heading in his direction, where he stood outside. He told her he would talk to them, she said.

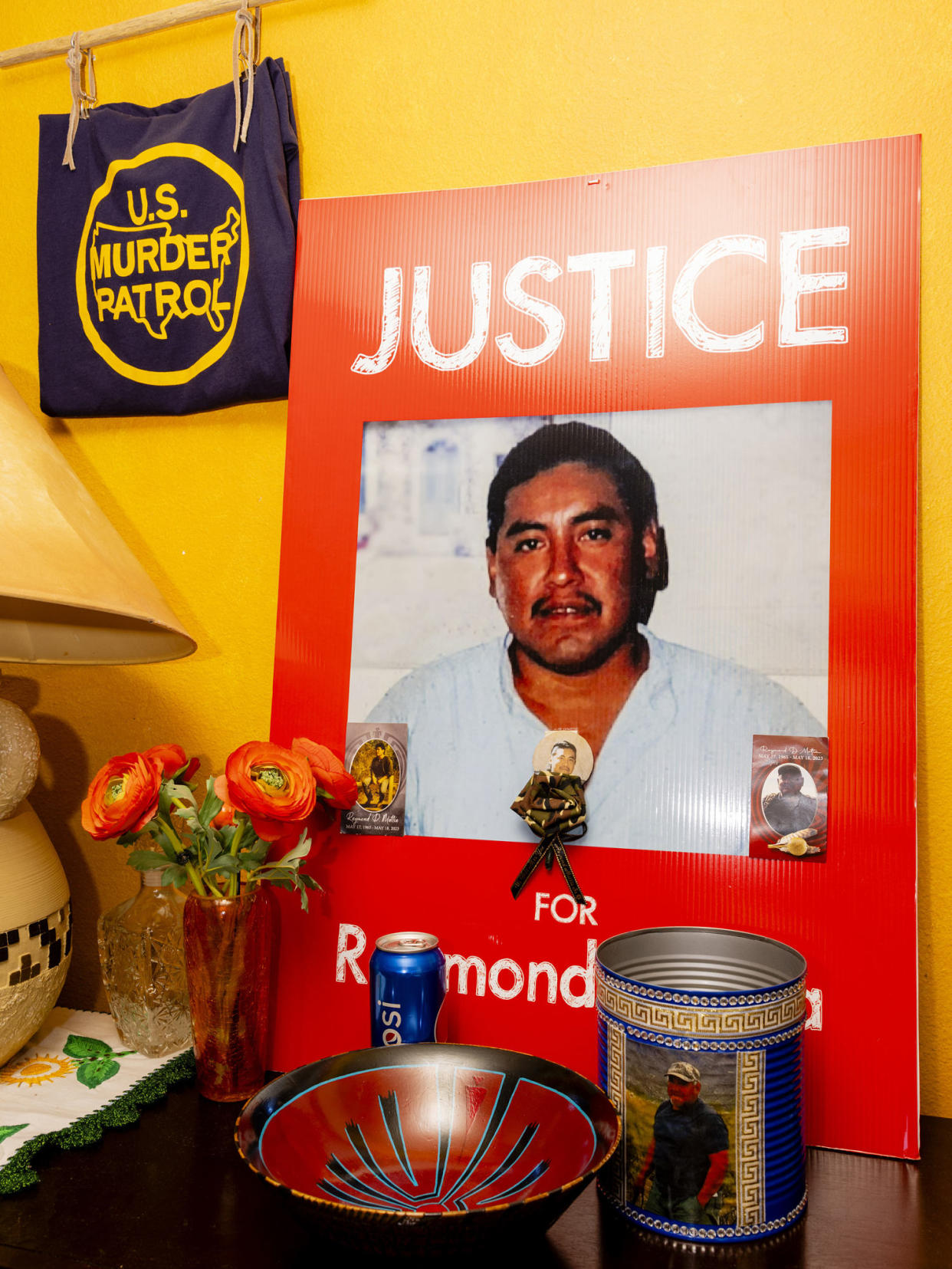

“And then I hung up with Raymond and like two seconds later, that’s when I heard all the gunfire go off,” she said in the interview at her home, wearing a red T-shirt bearing an image of her brother.

Clearly frustrated by the inability to bring constitutional claims against the agents, she and other family members are looking for other ways to seek justice.

The options are limited.

A law called the Westfall Act prevents similar claims from being brought in state court. Another law, the Federal Tort Claims Act, allows certain claims against the federal government for the conduct of officials but includes major exceptions.

Claims can be brought for actions taken by federal law enforcement under the act for things like assault, false imprisonment and malicious prosecution, but limits include no punitive damages and no jury trial. Plaintiffs sue the federal government, not the individual official.

It is damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act that the Mattia family’s lawyers will pursue.

“It’s a pale substitute,” said American Civil Liberties Union lawyer Scott Michelman, referring to the act. He represents protesters in Washington, D.C., who sued federal officers who aggressively broke up a 2020 protest opposite the White House in Lafayette Square. The Bivens claims were dismissed.

Even before the recent rulings it was difficult for plaintiffs to get a case in front of a jury, but claims could help provide leverage for a settlement. In 2017, for example, the family of Anastasio Hernandez-Rojas, a Mexican man who died after a violent struggle involving Border Patrol agents, received $1 million in a settlement. The lawsuit included both tort act and Bivens claims.

Lawyers who represent officers counter that there already is accountability — individuals can be disciplined and lose their jobs as a result of internal investigations. Officers can also face criminal charges, although such incidents are exceedingly rare.

“I see these as individuals. Whether they are innocent or guilty, they are human beings,” said Christopher Keeven, a Washington-based lawyer who represents federal officers in Bivens cases. “Maybe they just had a bad day. Maybe they did nothing wrong. Should you punish the individual or punish the government?”

'Sadness and anger'

On a recent sunny morning on the Tohono O’odham reservation, there was not a Border Patrol agent in sight as Annette Mattia and her daughter Nevarez pointed to bullet holes visible in the wooden walls of her brother’s house.

“No trespassing,” a sign posted on the building said.

The border, marked only by metal stakes pounded into the desert, is about a mile away, barely visible amid the cactus plants and scrub.

His family has built a memorial on the spot where Mattia died, featuring a simple wooden cross, a small statute of the Virgin Mary and a sigh saying “Justice for Raymond Mattia.”

Mattia had at times worked as an electrician and enjoyed various artistic pursuits, including drawing and making pottery. He served on the local tribal council and had two grown children.

Visiting the site brings back painful memories for his loved ones, who still find it hard to process what happened.

“He wasn’t acting erratic. He wasn’t trying to run. He was complying and they shot him. And as he lay dying, they continued to threaten to shoot him,” Nevarez said.

The family has placed a bottle of water in front of the memorial to provide nourishment on his journey.

“We leave the water, you know, for him,” Annette Mattia said. “In a sense, I feel he’s still around.”