DID RAP REALLY COME FROM JAMAICA?

No Parking declares a buckled old sign rusted onto a decaying, drooping pole, and no cars are parked in this downtown wasteland. Few even drive by. The gate to the broken-down old property behind is also rusted, and looks like it wouldn’t take much effort to push my way in. Yet for fear of being chased out, again, by a man with a machete, this time I just stand by the gate and peek inside.

You’d never know that this downtown stretch of Kingston, Jamaica, was nicknamed Beat Street because it teemed with dancehalls — one of the mighty venues being this crumbling landmark, Forester’s Hall.

More from Spin:

Afrika Bambaataa Sued for Alleged Sexual Abuse, Sex Trafficking of a Minor

New Music: Kaytranada – “Planet Rock (Planet Invasion Remix)”

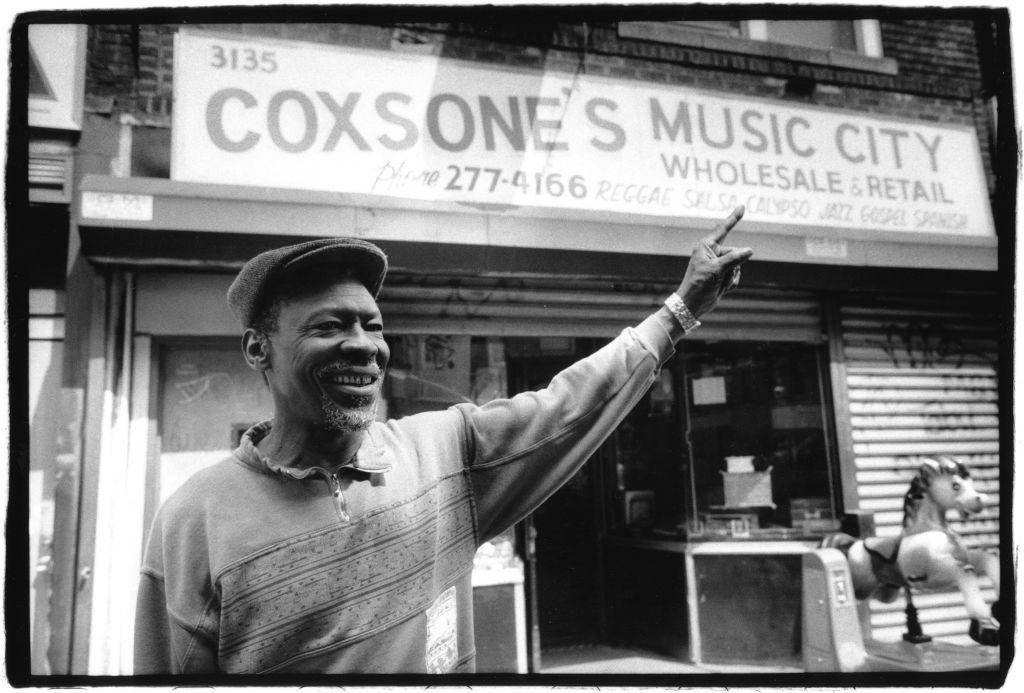

Today Forester’s Hall is a workshop for making coffins, but the bones remain of a dancehall where 800 revelers used to worship the latest records from Coxsone Dodd’s Downbeat Sound System.

Standing before this sacred ground, I imagine hearing “Schooling the Duke,” a beef-song that Coxsone played to “flop” his competition, Duke Reid. I smell curried goat and red snapper wafting through the blue mahoe trees. I see the ghost of King Stitt, standing on the platform in a suit, microphone in hand, chatting over the music.

Kingston is about 1,500 miles south of the Bronx, down across the Atlantic Ocean and some of the Caribbean Sea, but this deserted Kingston yard and others like it are fundamental to hip-hop history. Jamaicans call their island “likkle but talawa” — “small but mighty” — which it is, having birthed music like mento, ska, rocksteady, reggae, dub, and dancehall. And, from yards in Kingston’s downtown, and neighborhoods throughout the capital, Jamaica also plays a pivotal role in the evolution of rap.

Yet before Jamaica plays its part, we first need to go back to Harlem in the ’30s — to the late stages of the Harlem Renaissance, and to the art of jive.

Jive talking came from Harlem streets and jazz clubs, though the tradition has links to Africa and slavery. Jive was playful, crafty, and even competitive. Perhaps the best-known proponent is Cab Calloway, the famous Cotton Club band leader who conducted with a baton and sang in front of Duke Ellington’s orchestra, as well as his own.

Calloway spoke jive — “The jim, jam, jump on the jumpin’ jive makes you dig your jive on the mellow side.” He recorded jive in his songs, and in his own dictionary — Cab Calloway’s Hepster Dictionary: Language of Jive. Calloway established jive as a language and culture.

In the 1950s, jive furthered its reach through the embrace of Black radio disc jockeys. DJs like Texas’ Dr. Hepcat, aka Albert Lavada Durst, also published a jive dictionary which he used during his broadcasts. Back in New York, Tommy Smalls was Dr Jive, while Douglas ‘Jocko’ Henderson peppered his Rocket Ship show with phrases like “I’m back on the scene with the record machine.”

These American DJs spread jive not only over America but across the ocean. In 1950s Jamaica, where the recording industry had yet to establish itself, music was mainly consumed as a radio thing – catching transmissions from major cities far away. Bob Marley’s daughter Cedella told me that “when the stars and the moon and the wind were aligned just right, my dad could pick up far off American jukebox hits on his transistor radio.”

Young Jamaicans absolutely loved the hits and they couldn’t get enough of the jive-talking DJs: they idolized them for their power to not just introduce the music but to maintain the energy of the music. But most of all, they emulated the suave styling the DJs used to seduce and entertain the listener.

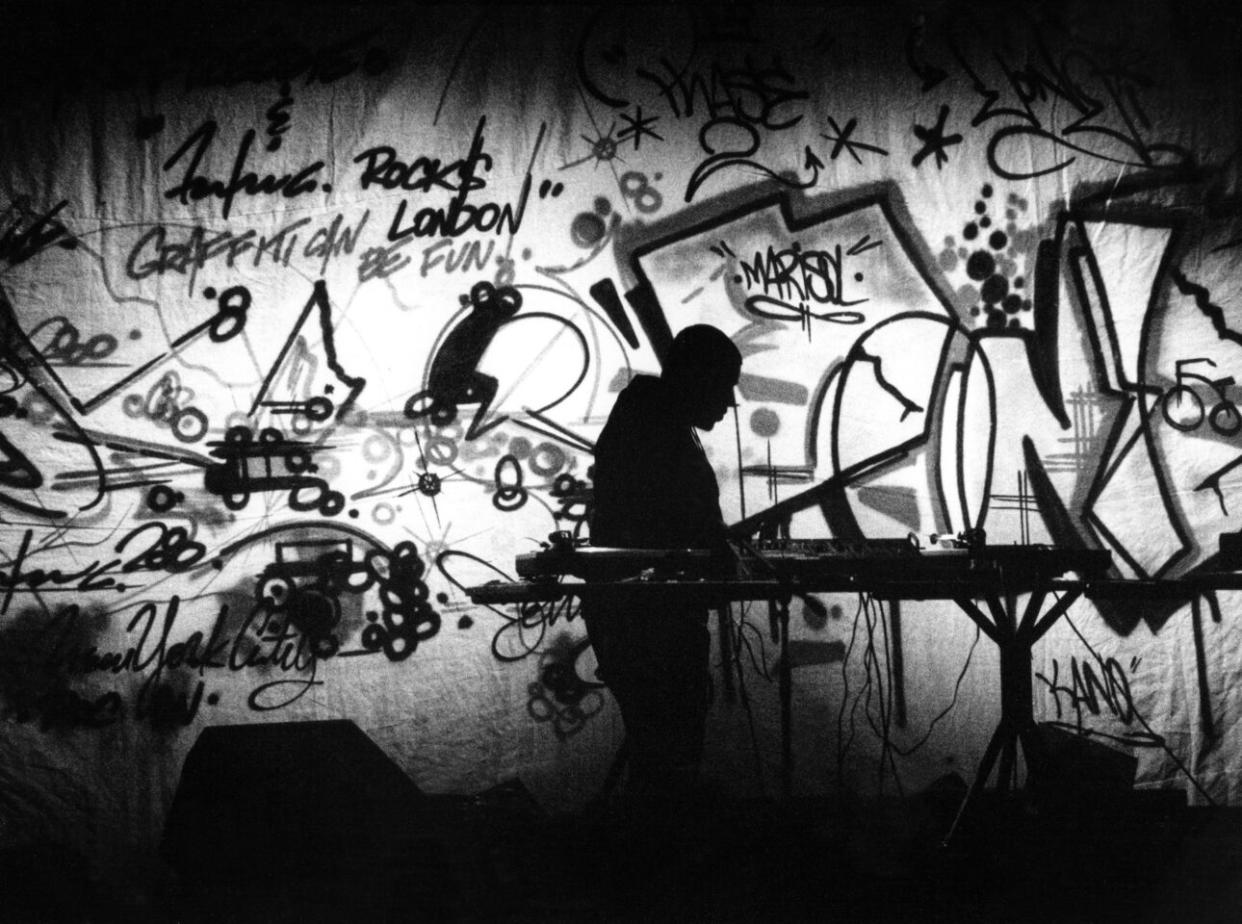

Sound-system operators commanded yards all over Kingston, like at Forester’s Hall. For amplification, they built ‘houses of joy’: homemade speakers built into wood cabinets, stacked large and high from bass to tweeter, competing with one another for the biggest sound and the biggest audience.

But although the sound-system operators curated the songs and wielded the power, it was the frontman — the DJ — who worked the crowd, just as the American DJ worked radio listeners.

Kingstons’s first DJ was Winston Cooper, known as Count Matchuki (Jamaica was a British colony until 1962 and many artists took royal honorific nicknames to take back power). Matchuki played the crowd, dancing or “dropping legs” and “toasting”. Like the jive of Cab Calloway, toasting used language for its rhythm, percussion, and style. It was improvised, freestyled, and deepened the music’s hold on the audience.

Matchuki told Beat magazine how he created his sound after hearing an American DJ in 1949: “That deliverance! This guy sound like a machine! A tongue-twister! […] And I say, I think I can do better. I’d like to play some recordings and just jive talk like this guy.”

At a Kingston record store, Count Matchuki picked up an American jive dictionary. “There would be times when the records playing would, in my estimation, sound weak […] so I’d put in some peps; chick-a-took, chick-a-took, chick-a-took. That created a sensation!” he told the authors of the Rough Guide to Reggae. Other toasts included the (now quite-innocent sounding): “If you dig my jive, you’re cool and very much alive. Everybody all round town, Matchuki’s the reason why I shake it down. When it comes to jive, you can’t whip him with no stick.”

Matchuki influenced a generation of toasters, including Winston Spark, known as King Stitt. Stitt rhymed and used percussive techniques like wild, shrieking yelps. His few recordings, like the song “Fire Corner,” feature him toasting: “No matter what the people say, these sounds lead the way. It’s the order of the day, from your boss DJ. I, King Stitt. Up to the top, to the very last drop.”

Another toaster, Sir Lord Comic, began hitting it in 1959, as he recounted in Deep Roots Music: “When the tune started into about the fourth groove, I says, ‘Breaks!’ and when I say ‘Breaks’ I have all eyes at the amplifier, y’know. And I says, ‘You love the life you live, you live the life you love. This is Lord Comic.’” He later recorded songs like “The Great Wuga Wuga,” clearly inspired by ‘Jocko’ Henderson. Jocko’s show, Rocket Ship, inspired a song of the same name recorded by the Skatalites, with Sir Lord Comic toasting.

The sound-system music and language of ’50s and ’60s Kingston was more than entertainment — it was an entire culture. And one of the kids born into this world was Clive Campbell, born in Kingston in 1955: a boy who would later move to the Bronx and make his name as DJ Kool Herc — the man who invented hip-hop.

Herc told me that his Kingston childhood primed him for what he would later do. “I remember growing up as a child in Kingston, Jamaica, in a place called Trench Town,” said Herc. “After that we moved to Franklyn Town. I lived on a place called Somerset Lane and King George had a sound system, and the dance was right down the block. The guys would bring the equipment […] and his yard was always zinc, all the way around […] with a strip of Christmas lights and you smell the curry goat and smell all the stuff. You hear the big bass rattling the rooftop and the zincs that surrounded the dancehall,” Herc said. “We find a little hole in the fence and you could see, because we kids are not allowed in there. I was hearing the records, Prince Buster and the Skatalites, and the main band back then was Byron Lee and the Dragonaires. And back then it wasn’t reggae, it was ska. All that time, I didn’t know my ear was getting trained, but that’s what happens with music.”

The sound system was Herc’s apprenticeship, and in 1967, aged 12, when he migrated with his family to the Bronx with his family in 1967 at 12 years old, he brought his schooling.

And as has entered global music legend, six years later, on August 11, 1973, Herc hosted a back-to-school party for his sister in a community room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue. He explained to me, “I did what’s called master of ceremony and imitate some of the words I hear. ‘I see you comin’ down to check I. Up it from the top from the very last drop.’ That’s Count Stitchy [King Stitt]. And I would do that. My history is undeniable. That’s how this music is. I wasn’t trying to disturb the lyrics. I was just giving the boys something they heard in the neighborhood, the slang coming up, you know? And calling people’s names up, giving alias names and stuff.”

Herc’s history undeniably shaped his future as an originator of hip hop. I’m careful not to claim he was the originator, as such claims are nearly impossible to prove and are problematic. Art is a collaboration and a culmination of many influences. But still the links between Herc, Jamaican toasters, and American jive are clear. When Herc toasted, “This is the joint! Herc beat on the point,” or “B-boys, B-girls are you ready? Keep on rock steady,” he was channeling Kingston.

Afrika Bambaataa, a protégé of Herc, talked to Reggae & African Beat about Herc doing what he’d grown up in: “He took the same thing that they was doing—toasting—and did it with American records.”

The Herculords — those who followed Herc — continued this tradition. Coke La Rock, a dancer and emcee for Herc’s sound system, created toasts, or raps, of his own, like: “There’s not a man that can’t be thrown, a horse that can’t be rode, a bull that can’t be stopped. There’s not a disco that I, Coke La Rock, can’t rock.” Like the Jamaican toasters, Coke boasted of his prowess in a competitive atmosphere to “flop” the competition. So too did Melle Mel, and the Sugarhill gang, and all who came in Herc’s wake.

If you wonder why this historical connection is not better known, it’s in large part because there’s not much of an historical record. Toasting was live. Sound systems were live. Experiencing music happened in the moment. There are few recordings of the original toasters, and even DJ Kool Herc himself didn’t record his art. Yes, toasting began before the recording industry developed, but the lack of recordings is more about the culture of toasting itself.

Or as Herc puts it, “They say, ‘Herc, why you never make a record?’ My record is hip-hop, my record is hip-hop.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.