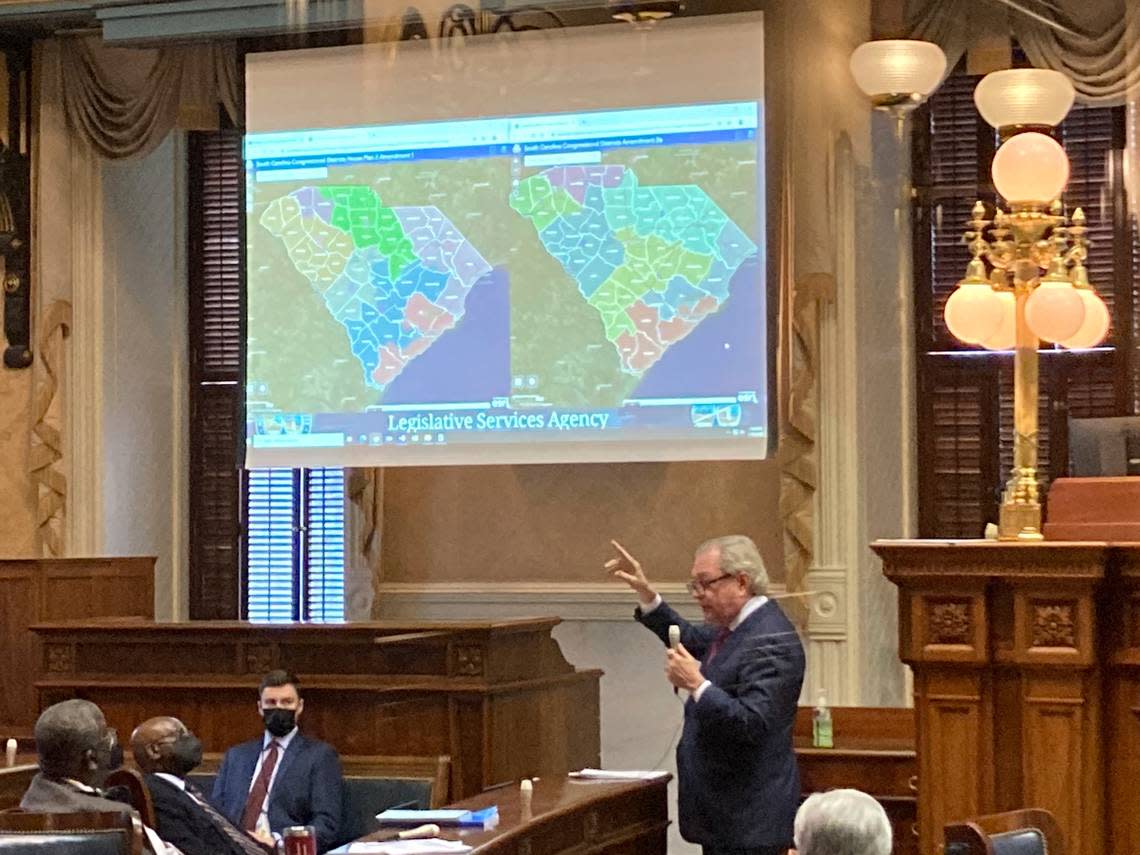

Did race drive recent changes to SC’s US House map? Or was redistricting purely political?

Only closing arguments remain in the trial over South Carolina’s new congressional map, during which state lawmakers have bluntly acknowledged that politics drove redistricting decisions.

The case centers on the constitutionality of the U.S. House map passed back in January by the Republican-controlled General Assembly.

The map, a slight deviation from the prior congressional map, solidified the 6-1 GOP advantage by expanding Republican influence in the coastal 1st District, held by U.S. Rep. Nancy Mace.

At issue is whether in doing so state lawmakers intentionally discriminated against Black voters in violation of the 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution, as the South Carolina chapter of the NAACP alleged in a lawsuit filed earlier this year in federal court.

The state NAACP, which is represented by several civil rights groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, claims lawmakers used race as the primary factor in drawing the 1st, 2nd and 5th congressional districts.

The state defendants deny that charge, arguing that politics, not race guided their line-drawing decisions.

During eight days of testimony earlier this month, witnesses for the plaintiffs have spoken to their perception that the Republican-led redistricting process discounted the input of Black residents and sidelined Black lawmakers in order to enact a congressional map that diluted Black voting power. To bolster those claims, the plaintiffs’ lawyers have put statisticians and political scientists on the stand to testify that complex quantitative and qualitative analyses of the map corroborated claims of racial bias.

The defense has countered that race played no role in the map-drawing process. The mapmaker and several lawmakers involved in the process testified that politics and adherence to traditional redistricting principles explain the map’s curious contours. To rebut the plaintiffs’ statistical evidence, lawyers for the defense presented their own redistricting expert who attempted to poke holes in that analysis.

While the revelation that political considerations largely informed Republican lawmakers’ mapmaking decisions may to some appear damning or, at least, distasteful, it is not illegal.

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2019 ruled that partisan redistricting is not reviewable by federal courts, meaning the judges in this case cannot find South Carolina’s map unconstitutional due to political bias, but must assess it on the basis of whether it discriminates against Black voters.

Closing arguments in the trial won’t be held until Nov. 22, more than a month after testimony concluded, and a decision by the three-judge panel of Mary Geiger Lewis, Toby Heytens and Richard Gergel will occur some time after that.

There is no deadline by which the judges must decide the case. The contested map will be used in the Nov. 8 general election, and would have been used even if the case had been decided sooner.

Plaintiffs argue US House map is racially gerrymandered

Lawyers for the South Carolina NAACP have attempted to make the case that the Republican-led redistricting process was not simply partisan, but racist.

Witnesses for the plaintiffs testified that Republican lawmakers ignored the testimony of dozens of Black residents who implored them to avoid splitting their communities, sprung maps on lawmakers without performing a racial bloc voting analysis and prevented York Rep. John King, the Black vice chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, from serving on the ad hoc redistricting committee and presiding over a redistricting hearing in the absence of the chairman.

Elizabeth Kilgore, a Black Sumter resident and president of the Sumter chapter of the state NAACP, testified that the interests of her community had been ignored.

“It’s like my Black community is left out of the process altogether,” Kilgore said at trial. “We vote, but we don’t count. We don’t have the opportunity, I feel, to elect a candidate of our choosing.”

Taiwan Scott, the only named plaintiff in the lawsuit and a member of Hilton Head’s Gullah community, echoed Kilgore’s concerns saying he also felt silenced and feared the further degradation of Gullah culture and influence without more active congressional representation.

“If we’re not afforded the opportunity to elect a voice, someone who will speak up on our historical concerns, we will continue to lose our property,” Scott said, “And without the people, you won’t have the culture.”

State Rep. Kambrell Garvin, a Black Richland Democrat, was one of multiple witnesses who testified that Republican lawmakers seemed to prioritize the concerns voiced by white residents over the interests of residents from more diverse communities.

Specifically, Garvin said, a cadre of Beaufort County residents were granted their request that Beaufort County remain in the 1st Congressional District, while Charleston County residents were not given the same consideration when they protested about being split between the coastal 1st and the sprawling 6th Congressional District, represented by U.S. House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, which stretches all the way to Columbia.

North Charleston residents are lumped into the same district as Columbia residents, but the northern Richland community of Blythewood, where Garvin lives, is in a district with Lexington and Aiken counties, he lamented.

“I think the way the maps were drawn puts African Americans at a disadvantage,” Garvin testified. “We really don’t have an opportunity to impact or sway the congressional election. And I think it’s really important that whether you’re an African American politician or a white politician, that you have to be accountable to all voters.”

Democratic state Sens. Margie Bright Matthews, of Colleton, and Dick Harpootlian, of Richland, who both served on the Senate redistricting committee, testified they weren’t asked for input on the congressional map or given a chance to review it before its release.

“I assumed somebody would call me, ask me to come into the map room, look at it and get my comments,” Harpootlian said. “So, when the plan came out the week before Thanksgiving, to say I was taken aback would be an understatement. I was outraged.”

He described the process, which he jokingly referred to as the “Immaculate Deception,” as a “fait accompli.”

“The train had left the station,” Harpootlian said. “And whatever we said, whatever our concerns were, were not to be considered.”

He and state Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter, D-Orangeburg, both testified to their concern that Republican leadership had not statistically analyzed whether the map diluted Black voting power by packing or cracking Black communities.

Cobb-Hunter, the House’s longest-serving member and a veteran of three redistricting cycles, called the failure to conduct a racial bloc voting analysis an omission and a disservice to voters.

She also questioned leadership’s decision not to let King, an outspoken critic of the General Assembly’s mapmaking process, run a House Judiciary Committee hearing on redistricting in the absence of Chairman Chris Murphy, R-Dorchester.

King, the Judiciary Committee’s vice chair and a member of its Election Laws subcommittee, testified to feeling “disrespected” by lawmakers throughout the process and said he felt his exclusion from the ad hoc committee was racially motivated.

Had he been allowed to chair the Judiciary Committee hearing in question, King said, he would have been more deliberate about assessing and discussing the map under consideration at the time.

“We would not have rushed and voted that particular piece of legislation out that day,” he testified. “I would have given it due diligence.”

Numerous experts employed by the plaintiffs to statistically analyze the enacted congressional map testified to its alleged racial bias.

Moon Duchin, a Tufts University mathematics professor with expertise analyzing redistricting maps for “excessively race-conscious line drawing,” testified that “all signs” pointed to the conclusion that South Carolina’s congressional map had “cracked,” or fragmented Black communities in order to dilute their voting power.

Duchin said that even when controlling for party affiliation, which often is closely correlated with race, her analysis found evidence of racial bias. Candidates preferred by Black voters, she said, fare far worse than generic Democrat candidates.

Baodong Liu, a University of Utah political science professor who specializes in racial polarization analysis, also testified that racial considerations, not partisan affiliation had predominated, according to his review.

“The message is clear,” Liu said. “Blacks are much more likely to be put in the split counties as opposed to the non-split counties compared to whites.”

Defense argues race not a factor

The defendants rebutted the experts’ claims with their own redistricting expert, Sean Trende, senior elections analyst for RealClearPolitics, a political news and polling analysis website.

Trende testified the analyses performed by the plaintiffs’ experts “misses the forest for the trees” and argued it did not appropriately control for the criteria lawmakers actually used to inform their map-drawing decisions.

Lawmakers were not starting from a blank state when they created the map, as he testified some of the expert analysis assumed, but actually attempting to improve upon the prior map while making as few substantive changes as possible.

House and Senate Republicans were primarily concerned with retaining the cores of existing districts, protecting incumbents and ensuring partisan political advantage, Trende testified, and the map’s boundaries are consistent with those goals.

Many of the splits identified by the plaintiffs as most concerning and indicative of racial bias existed in the prior map and have been in place for decades, he said.

At the end of the day, the Black voting age population, or BVAP, in the 1st Congressional District, about which much of the plaintiffs’ testimony focused, is virtually unchanged.

“The net effect of these moves on the racial composition of these districts is minimal,” Trende said when asked about the map’s handling of the 1st and 6th districts. “But moving these districts reduces the Democratic performance in District 1 appreciably, as these residents voted for Joe Biden by an 18‑percent margin.”

A series of Republican politicians and the staffer who drew the enacted map all testified to that point.

The map, they said, was drawn to enhance Republican political advantage in the coastal 1st District, which has evolved into a swing district in recent years, but had not used race to accomplish that goal.

“I think saying that (partisanship) was a factor is an understatement. It was one of the most important factors,” Senate Majority Leader Shane Massey, R-Edgefield, testified. “The Senate was not going to pass a plan that sacrificed the 1st.”

Legislative cartographer Will Roberts testified that he never drew any maps that were motivated by race, used racial targets or used race as a proxy for partisanship at the request of lawmakers.

He said he used the existing map as a benchmark, as he always does when drawing maps, and attempted to make minor changes that balanced the population while retaining the cores of districts.

Starting from the benchmark map in this case was particularly important, Roberts testified, because it had survived a court challenge during the last redistricting cycle and had been pre-cleared by the U.S. Department of Justice under former President Barack Obama.

In addition to following traditional redistricting principles, including taking incumbency and political considerations into account, Roberts testified that he also incorporated requests from Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Luke Rankin, R-Horry, who chaired the Senate redistricting committee, and two U.S. House members — Rep. Joe Wilson, R-Springdale, and Clyburn, D-Columbia.

Rankin directed him not to touch the 7th District, which encompasses the Pee Dee and Grand Strand, more than was necessary; Wilson asked him to keep Fort Jackson, the Army’s largest basic training base, in his 2nd District; and a Clyburn staffer provided him a copy of a map and said the Black Democrat preferred a “minimal change” plan, Roberts said.

He relied “heavily” on the map Clyburn’s staffer submitted, he said, using it as the starting point for the original staff plan, which over multiple iterations evolved into the plan lawmakers ultimately adopted and the governor signed into law.

“The enacted plan is really a modification of the staff plan, which originated from the (Clyburn) plan,” Roberts testified.

He acknowledged the enacted plan was drawn to increase GOP advantage in the 1st District because the General Assembly would have rejected any plan that didn’t transform that district into a safe Republican seat.

Roberts said that while he hadn’t considered race when drawing the original map, he later examined its racial makeup after former Congressman Joe Cunningham, the current Democratic candidate for governor, alleged at a public hearing last year that it had been drawn along racial lines.

“We had no idea what we had done, because we didn’t look at race when making modifications, we were looking at strictly political data,” Roberts testified. “So, after he raised those concerns, we went back and started analyzing what we had changed.”

Their review, he said, determined that Cunningham’s claims were false.

“The areas (around Charleston) that we moved were … predominantly white areas,” Roberts testified. “They were majority Democratic areas.”

State Sen. Chip Campsen, R-Charleston, a redistricting committee member who presented what became the enacted plan on the Senate floor, testified that his goal was to create a map favorable to Republicans that still adhered to traditional redistricting principles.

When given the choice between a district that kept more of Charleston in the 1st District, but performed worse for Republicans, and a district that included less of Charleston, but was better for GOP candidates, he chose the latter, Roberts testified.

Campsen said he intentionally avoided looking at the racial implications of the map and relied on staff attorneys to notify him if district lines appeared to run afoul of the law.

Campsen, who at the time the map was debated on the Senate floor denied it was a partisan gerrymander, asserted at trial that his prior statements had been truthful.

He claimed he hadn’t put partisanship above all other considerations, but rather balanced political interests with adherence to traditional redistricting principles, even though it meant turning the 1st District into “just barely a Republican district.”

“When they said this is a partisan gerrymander, and I’m losing Republican votes because I’m sticking with the geographic boundaries, I had to refute that,” Campsen testified. “A partisan gerrymander, in my mind, is when you subordinate everything else to the partisan numbers, and I did not do that. There’s nothing further from the truth than that.”

Text messages state Rep. Jay Jordan, R-Florence, received from colleagues and staffers during the redistricting process appear to confirm lawmakers’ overarching partisan motivations.

Jordan, who chaired the House redistricting committee, read aloud in court several of the texts he received that spoke to the political considerations driving the process behind the scenes.

One text, sent by Patrick Dennis, chief counsel for the House and chief of staff to the speaker, explained that if Charleston County was kept whole in the 1st District, as many Democrats and members of the public preferred, the district would not be a safe Republican district.

Another text on the same chain, sent by state Rep. Weston Newton, R-Beaufort, relayed that he’d heard the Senate would accept a map that gave Republicans a 7-point advantage in the 1st District and asked what tweaks the House could make to the Senate map.

“At this point, I’m ready to just adopt their plan,” Dennis responded, according to the text read at trial.

Congressman Jeff Duncan, R-Laurens, also texted Jordan about the Senate map, telling him South Carolina’s federal delegation supported it unanimously.

“It is better for the 1st for sure,” he texted, according to court testimony.

The House ultimately adopted the Senate plan without changes.

To bolster their contention that the map had not been designed in a racially discriminatory way, the defense called state Rep. Justin Bamberg, a Black Democrat and member of the House redistricting committee, to testify on the penultimate day of testimony.

Bamberg, whose own Bamberg-based House district went from a tossup to a safe Democratic seat as a result of redistricting, testified that politics, not race, had animated redistricting decisions, at least on the House side.

“I’m one of the loudest Democrats at the State House. I’m engaged in almost every debate of substance,” he testified. “If I had thought that (the plan was intentionally racially discriminatory), I would have taken the podium, and I would have said it, right? There’s no doubt in my mind about that.”