Designer Willy Chavarria is Doing It His Way

On a crisp fall evening, Willy Chavarria meets me in the lobby of Fouquet’s, a Parisian hotel import in New York’s TriBeCa neighborhood. It’s two days after Chavarria won Menswear Designer of the Year at the Council of Fashion Designers of America Fashion Awards, four days after he was named Designer of the Year at the first-ever Latin American Fashion Awards, in the Dominican Republic, and two months after he staged one of the strongest and most moving shows of New York Fashion Week’s Spring 2024 season. Chavarria, who lives nearby, walks into the sepia-toned lobby right on time. He’s wearing black trousers, a black tee, and a black blazer, with chunky clogs and a chest full of layered gold chains and rosaries.

Chavarria smiles and cuts right to the chase. “Can I order for us?” he asks. I, of course, oblige. “We’ll have two Belvedere martinis, shaken, glasses rinsed with vermouth, a sidecar of olive juice,” he tells our server, “and two olives, please.” When the drinks arrive, Chavarria takes a sip. “Perfect,” he says.

This is someone who knows who he is and what he wants. “There is,” he says, “an old-guard way of thinking where you enter the fashion world and you need to become this pretentious, snobby, superficial person.” In work and in life, Chavarria is anything but. He launched his namesake line in 2015, building a loyal following for his club-kid streetwear: baggy jeans, graphic tees, utilitarian bomber jackets, and anoraks. Recent collections have seen his vision evolve. There is more suiting and eveningwear, including gowns and tanks and trousers crafted with sequins and taffeta. Always, there’s a political undercurrent; his designs challenge the ways we perceive masculinity and sexuality. Often, they are a commentary on his Catholic upbringing and influenced by his Mexican-American heritage. He’s created gothic oversize outerwear and suiting that play on ideas of priestly garb, zoot suits, and T-shirts and hoodies that feature artwork from the subversive Mexican graphic designer Carlos Graciano, known as Sad Papi.

“I think it’s very important to make sure that we include humanity in our work.”

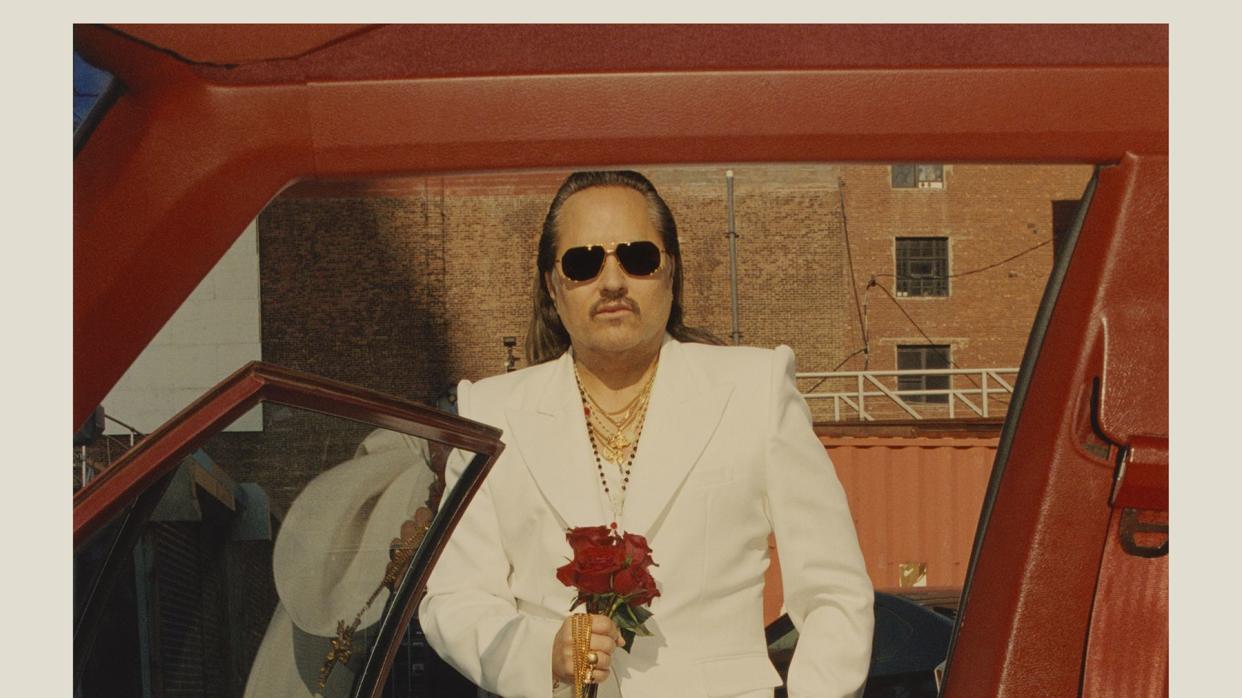

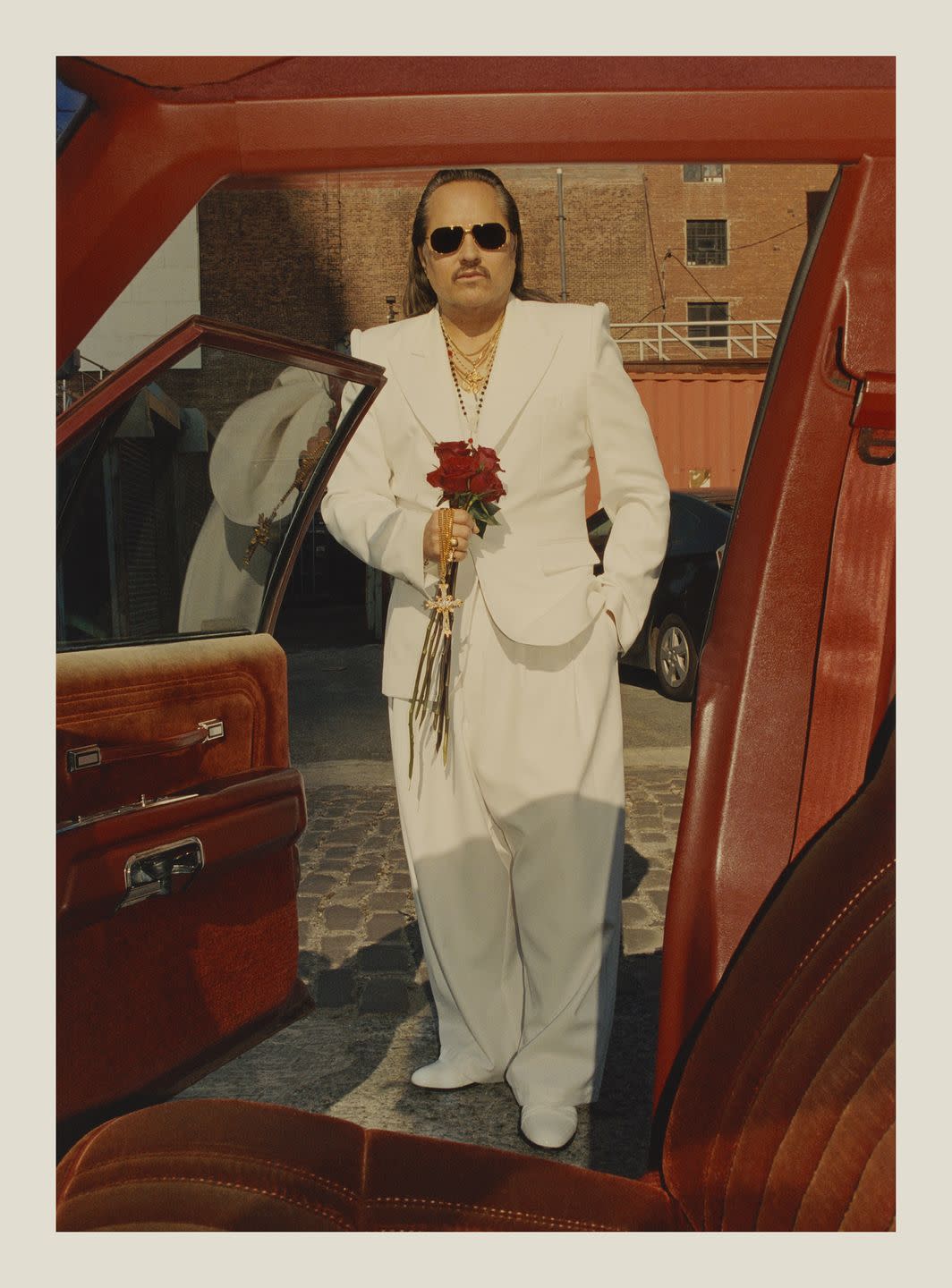

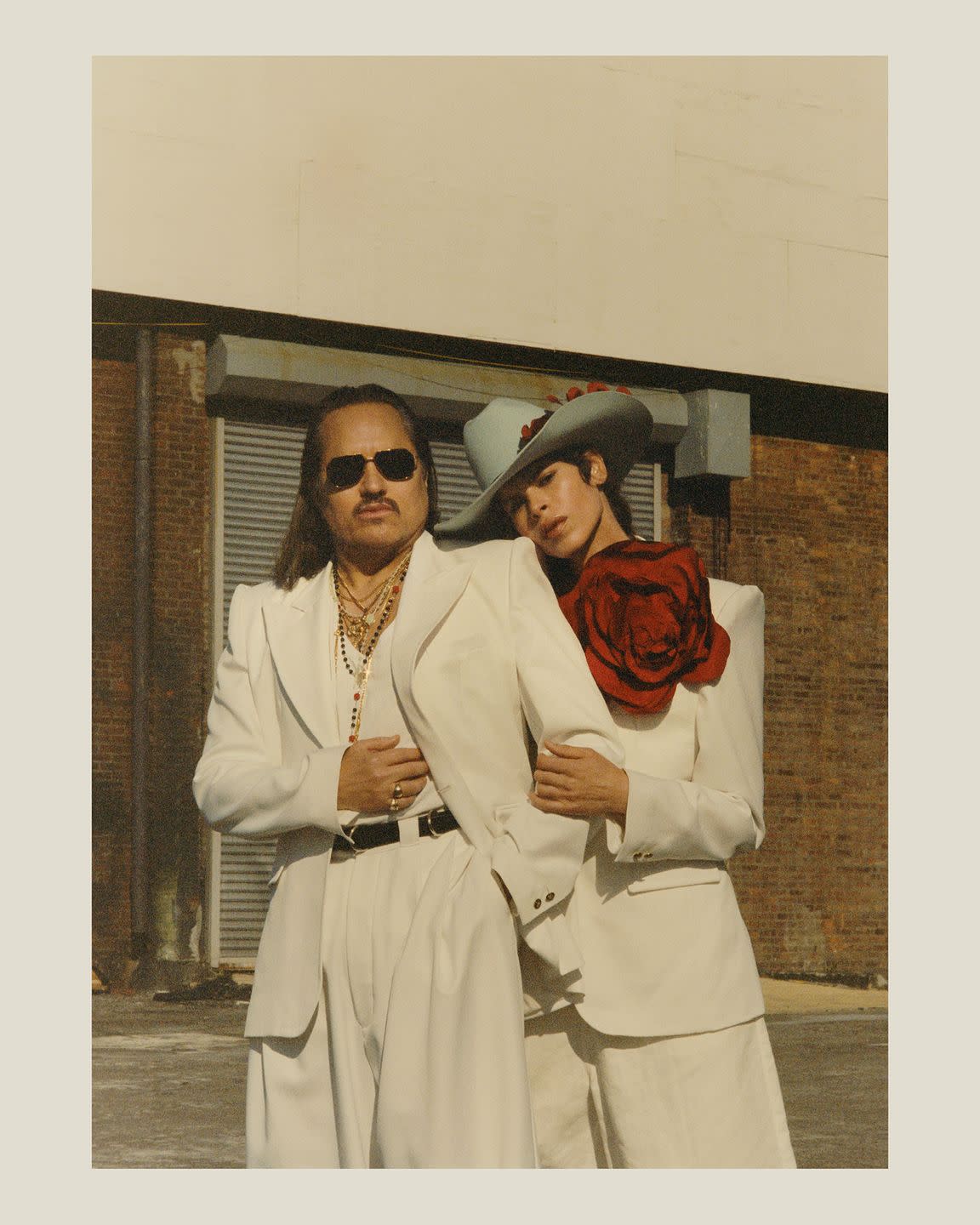

Chavarria’s Spring 2024 collection was a breakthrough—a lineup that celebrated his Latino heritage and included exquisitely tailored white suit jackets pinned at the lapel with giant red flowers. There were also khaki trousers, basketball shorts, and tees printed with an imagined logo for a fantasy youth group named Grupo Nueva Visión por Vida (New Vision for Life Group). Three couture-like pieces closed the show: voluminous cape gowns tied with thick bows at the neckline. “I would say that’s the first show I’ve ever done with that kind of lighthearted feeling, and I wanted to do that intentionally because all of my other shows have been so dark,” he says. “To work in an industry that is based on looking good and feeling good, which is not the deepest thing in the world, I think it’s very important to make sure that we include humanity in our work.”

Born into an immigrant farming community on the outskirts of Fresno, California, in 1967, Chavarria was fascinated by the everyday style of the farmers and workers around him: his parents’ friends who went off to work each day in Dickies pants and T-shirts from Kmart and the local women who wore black veils to church on Sunday. His parents were involved in social-justice movements, particularly in activism for farm workers during the 1960s and ’70s.

His mother, Gwen, who now lives in Santa Maria, California, remembers when he first started documenting the world, and the people, around him. She recalls that Chavarria “developed early in walking and talking, so we knew he was special from about five months old.” She adds, “We saw his abilities in his early drawings of an amusement park in Fresno. Using tiny, clothed stick figures, he meticulously drew the people he saw there: hair flying, arms stretching up, legs running, families at the park. It was as if the figures were alive.” From about three on, she says, Chavarria “was never without paper and pen.”

Chavarria’s childhood sketching and keen observations eventually led him to a degree in graphic design from the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. His first job in fashion was in the stockroom at the underwear and loungewear brand Joe Boxer. He worked his way up to a design position where he was mentored by founder Nick Graham. (They’re still friends today.) In 2010, Chavarria and his husband, David Ramirez (with whom he’s been together for 21 years), opened a store in New York’s SoHo neighborhood called Palmer Trading Company. It stocked vintage items and an in-house line, all inspired by Americana.

Ultimately, Chavarria felt pulled to create something personal—clothing that looked more like his own American story. He launched his namesake brand in 2015 and shut down the shop a year later. Now, his line is stocked by luxury retailers like Dover Street Market, Bergdorf Goodman, and Browns in London.

It’s not the traditional fashion trajectory. Chavarria’s singular path has helped shape his drive to create political dialogue through his work. He seeks to highlight the unassuming beauty of the banal as well as spotlight those Black, brown, and queer communities far too often overlooked and uncredited by fashion. “Fashion has always started on the streets,” he says. “I know in the old days, there was couture, and it started with royalty and all that, but now it starts in the streets. And it always started with Black and brown people.”

It’s dark out when we finish our drinks. Chavarria waves a familiar goodbye to the hotel doorman. He insists on walking me to find a cab. “I’m like a grandma; I want to make sure you get there safely,” he says with a laugh and another hug goodbye.

“People often use community as a buzzword; same with inclusivity. They’re really played out.”

There’s a steer skull hanging on a column toward the entrance of Chavarria’s airy Brooklyn studio. On another column hang several crosses, and propped up against the walls are more eclectic sources of inspiration: a framed print of Patti Smith, a photo of a young Naomi Campbell, a blown-up image from a vintage underground Latino porn magazine. Everyone on Chavarria’s small team chips in, whether it’s helping Chavarria sketch the next collection, put together the mood boards, or send out orders. “No worries. I’ll totally help you pack all of that up in a bit,” Chavarria says when one assistant mentions how much shipping there is to do.

Kayla Mayhew, Chavarria’s close friend, whom he considers a muse and who has helped cast his shows, has witnessed firsthand the power of the designer’s convictions. “I think what makes his work so special is how he always stays true to himself,”

she explains. “And his work is important to American fashion because of the way it makes people feel and the way he makes people feel. Being around him, you can really feel that he truly loves what he is doing, which is always a great reminder to go toward your craft.”

When I bring up the notion of community in the studio, Chavarria acknowledges the importance of the people who surround him but is hesitant to throw the term around when it comes to talking about his brand. He says, “People often use community as a buzzword; same with inclusivity. They’re really played out. But at the same time, American fashion is being guided by these new voices.”

Chavarria’s response to these overmarketed ideas of openness and empowerment is to lead with radical honesty. “If you’re showing something outward-facing that isn’t real from every aspect of your own creation, then it’s never going to come across as sincere,” he says. “People are way too smart now. They’ll see insincerity immediately and from a business perspective too. Some bigger businesses have come to me recently who want to work together, and they say, ‘We want to show community.’ And I always ask, ‘What do you mean by community? There’s a food community. There’s a theater community. What community are you talking about?’ And it has nothing to do with the inner workings of their brand. They’re just trying to look like they’re on the bandwagon of connecting with different social classes.”

“It’s about fit and what looks good on our bodies.”

When Chavarria sketches, he doesn’t think about gender but instead starts with a body and a fit. The drawings are imprecise on purpose, a little rough around the edges. His label is categorized by retailers as menswear and is popular with New York Giants quarterback Tyrod Taylor, rapper YG, and singer J Balvin, but more women and femmes are catching on. Over the past year, his eveningwear has been worn by actors Renée Rapp, Tessa Thompson, and Dascha Polanco. He also designed custom looks for two women at the CFDA Fashion Awards: rapper Tokischa, who was his date, and model Paloma Elsesser. And while his nipped waists and strong shoulder cuts may look right at home in the world of womenswear, Chavarria’s goal is not to ascribe to any kind of gender binary.

“Those barriers are deeply instilled in the fashion industry because you have a men’s floor and a women’s floor, a men’s buyer and a women’s buyer, a men’s tech designer and a women’s tech designer,” he tells me. “All of those things can still be valid, but I think what we need to do is take down the barrier of where we need to shop, which area we need to shop in, and make it more about size inclusivity.” He adds, “It’s about fit and what looks good on our bodies. But normally, a male-presenting person, regardless of gender, will prefer to shop the menswear department and a female-presenting person prefers to shop in the womenswear section. So I don’t think that completely erasing gender identity is the answer. Any trans female that I know does not want to buy gender-fluid clothing; they want women’s clothing.” He goes on to say, “Femininity and masculinity still exist, and they don’t have to be toxic. We can love them, and we can include them and be accepting of one another.”

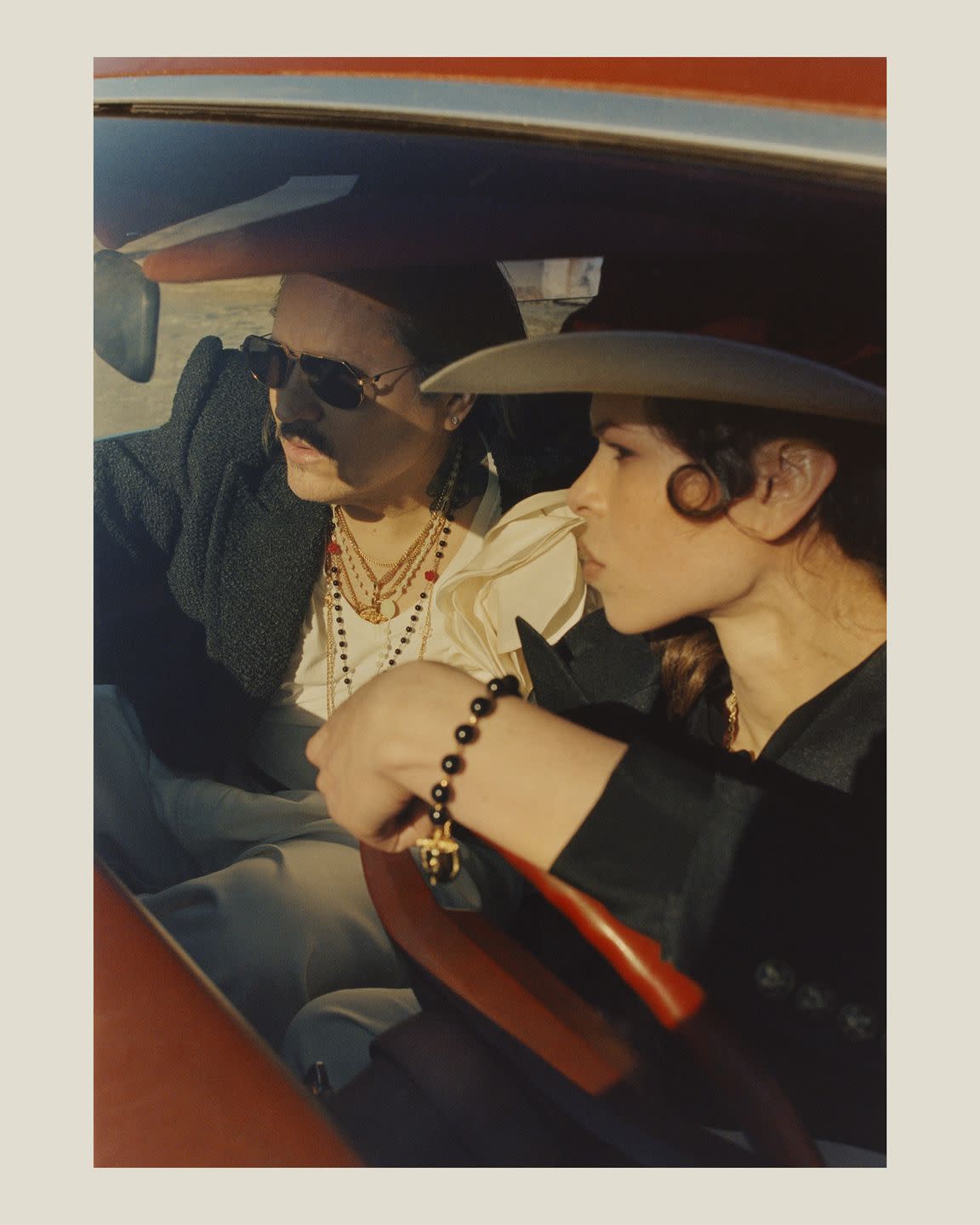

Model and activist Amara Gisele, who is trans and has walked the runways for labels like Mugler and Balenciaga, is Chavarria’s newest muse. “Willy embraces his queerness with joy and isn’t afraid to design through this lens,” she explains. “He inspires me through his fearlessness.”

Taking risks is what Chavarria has done his whole life, and as his husband explains, the business has succeeded because of this. Chavarria, Ramirez says, “is a true entrepreneur in the sense that he has been able to reach global acclaim and recognition with little to no outside investments.” He adds, “Having less restrictions around gender and sizing norms allows for a more open and honest shopping experience, and in the end, that will drive sales and revenue.”

Fashion is a tough business—a “grueling” one, Chavarria says. But fashion is how he feels he can most genuinely make an impact in a society that is only getting more hostile and difficult to navigate. For now, Chavarria’s eyes are trained forward, and he’s looking to build out a jewelry collection and integrate more sculptural tailoring and luxury fabrics like bouclé and silk faille into his designs.

“Fashion here is different because we have this wave of realness that’s lifting the industry up now,” he says. That’s the magic of his clothes but also of him. Chavarria uplifts but also grounds every space he enters, and he’s well on his way to grounding American fashion too.

All clothing and accessories, Willy Chavarria. Styled by Miguel Enamorado. Model: Amara Gisele; hair: Edward Lampley for Oribe; Makeup: Maud Laceppe For MAC Cosmetics; casting: Anita Bitton at the Establishment; production: Will Roan at WR Productions. For more shopping information, go to bazaar.com/credits.

You Might Also Like