A desegregated USC began with 3 students. Their legacy is now forever cemented on campus

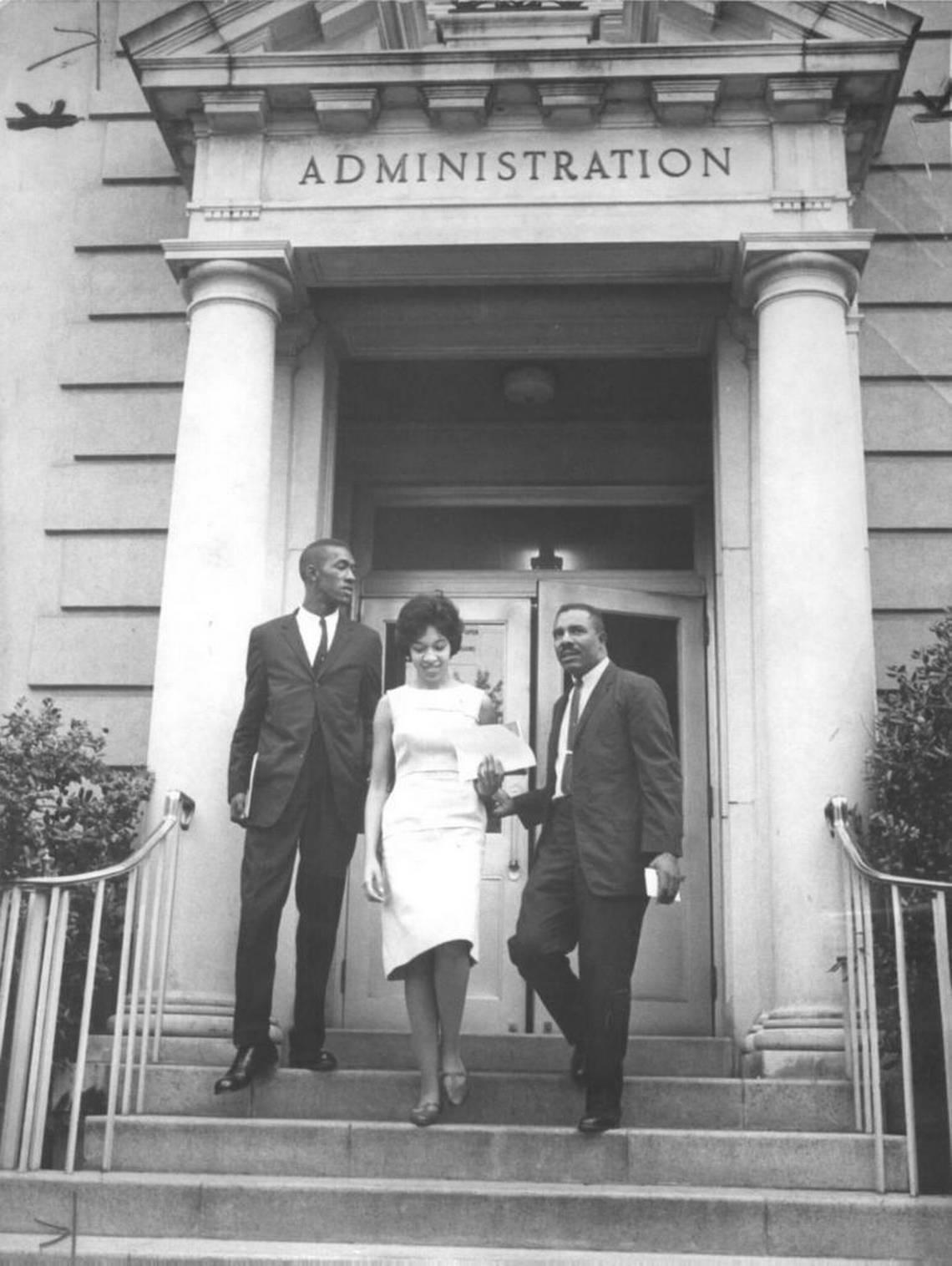

On a hot day in September 1963, Henrie Monteith Treadwell, Robert Anderson and James Solomon Jr. descended the steps of USC’s Osborne Administration Building and walked toward Hamilton College, where they would first register for classes. They did so not with fear, Treadwell said, but while holding their breath.

After nearly a century of barring students of color, the University of South Carolina was finally desegregated.

“People must understand that my walking across that threshold was not the end of the story,” Treadwell said in September at the groundbreaking for a monument to honor the three students. “My walking across that threshold was the beginning of a story.”

A 12-foot bronze sculpture commemorating the iconic photo of that very moment now stands proudly on USC’s historic Horseshoe near the McKissick Museum, a permanent celebration of a turning point in the university’s history. The statue was unveiled during a ceremony on Friday morning.

“It’s a special moment for us,” said USC Board Chairman Thad Westbrook.

The monument is at the “heart” of campus, said Dorn Smith, USC board member and former board chair. The board hand-picked its location so that every man, woman and child who comes to visit will walk past it and enjoy it.

Treadwell, a Columbia native, graduated at the top of her high school class. And though it was nearly a decade after the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which desegregated public schools, Treadwell’s application to USC was rejected in 1962.

With the help of civil rights attorney Matthew Perry, she and her family sued. And won. When the case made its way to the courtroom, university registrar Rollin Godfrey admitted on the stand: Treadwell had been rejected on the basis of race. The court victory opened the doors to Solomon and Anderson too.

Treadwell’s uncle’s home was bombed. The three students experienced harassment — from threatening calls to racial slurs. Unbeknownst to the trio, South Carolina Law Enforcement Division vehicles were posted around campus their first day, and so were undercover agents.

But unlike the violence and unrest that desegregation brought to many southern universities, USC’s integration was a relatively peaceful transition and the three went on to earn degrees from the school. In 1965, Treadwell became the university’s first Black graduate since Reconstruction, and the first Black woman graduate ever.

“I am the embodiment of the realization of the dreams of equality of many ancestors,” Treadwell said. “But today is not about me. It is about an institution that has opened its doors and ... building and erecting a homestead for all who would come, regardless of race, creed or color.”

USC board member and former NBA Hall of Famer Alex English grew up in Columbia and lived off of Barnwell and Gervais streets. He remembers, at that time, not being able to walk across USC’s campus to get to his elementary school.

“These three brave students stepping forward and putting their lives on the line ... so that all African Americans and people of color would get the opportunity to be educated at this great university,” said English.

The university Board of Trustees approved the creation of the monument in 2022 with unanimous support, on the eve of USC’s 60th anniversary of desegregation. The board later selected world-class Jamaican sculptor Basil Watson to design and craft it. Watson called the project a “labor of love.”

“USC is a historic university, but its also a modern university. Our relevance depends on our ability to look forward,” university President Michael Amiridis said. “To do this, we must shoulder the truth our past.”

Several years ago, a push was made to change the names of USC buildings that referenced segregationists and slave owners. The effort was effectively shut down by the state’s Heritage Act, which requires legislative approval to change state-owned buildings named for historic figures.

But the desegregation monument, along with the naming of Celia Dial Saxon Hall after the prominent Black educator and Civil Rights advocate, are part of a “forward-looking” approach to putting the university’s history into context, Westbrook said.