DeSantis praised a Miami Beach homeless law. Is it as ‘compassionate’ as the mayor says?

Reality Check is a Herald series holding those in power to account and shining a light on their decisions. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email our journalists at tips@miamiherald.com.

Last week, at a press conference in Miami Beach where Gov. Ron DeSantis signed legislation to prevent homeless people from sleeping in parks and other public spaces statewide, the governor lauded Miami Beach’s efforts to address “camping” locally by tightening a law that subjects people to arrest for sleeping outside.

DeSantis and Miami Beach Mayor Steven Meiner both touted the city ordinance not only as a way to promote public safety and improve residents’ quality of life but also as a compassionate approach that gives homeless people an opportunity to receive services and placement in a shelter before facing arrest.

The governor drew parallels between the Miami Beach ordinance and the new state law that allows residents and businesses to sue local governments, starting Oct. 1, if they fail to prevent public sleeping by placing people in shelter beds or building homeless camps that provide security, sanitation and behavioral health services.

“What the mayor is doing, he’s providing them, ‘Here’s where you can go,’” DeSantis said of Meiner. “If they refuse, then you absolutely have a right to arrest them and remove them from being effectively a public nuisance at this place.”

READ MORE: Touting ‘law and order,’ DeSantis signs bill allowing homeless camps in South Florida

But a Miami Herald review of enforcement of the ordinance raises questions about whether it is being deployed as a tool to improve the lives of homeless people, as city officials have suggested.

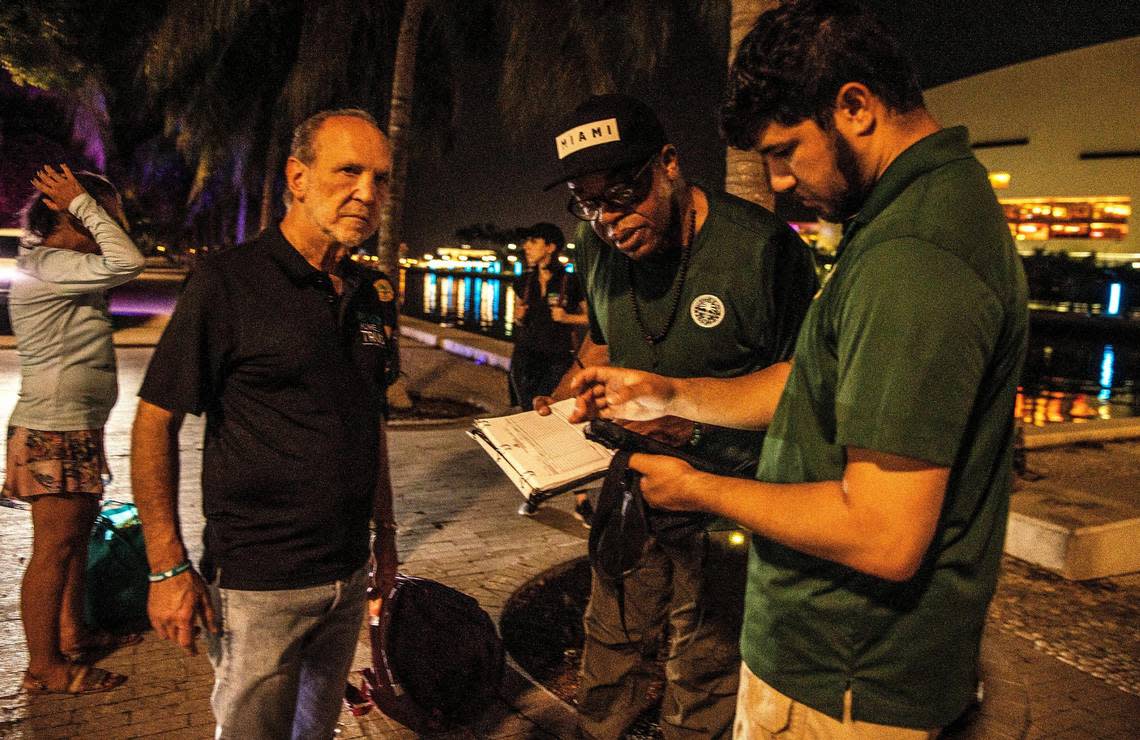

Police reports from nearly two dozen camping arrests made since the revised ordinance took effect, as well as body-worn camera footage from several of those arrests, show Miami Beach officers asking only vague questions about whether homeless people want shelter or other assistance before detaining them. Officers do not appear to discuss the availability of beds in specific shelters, offer transportation to the shelters or explain that declining services will result in their immediate arrest.

In one case on Nov. 29, an arrest report says officers “asked the defendant if he would like assistance from a homeless resource officer or assistance to get access to a homeless shelter. The defendant responded with no and did not want assistance.”

Body-cam footage, however, reveals a slightly different version of events. The video shows that three police officers on ATVs approached the man in a sleeping bag on the beach near Third Street around 11:30 p.m. After establishing that the man was homeless and had been sleeping on the beach for three years, an officer asked twice whether he wanted “help.” The man said “no.” The officer asked: “No homeless shelter?” The man said “no” again.

During a brief back-and-forth, the man told an officer he had been living on the beach since he “found God.” As the officer asked if the man had anything in his pockets, the man stood up and put his hands in the air. The officer then placed him in handcuffs.

The man was charged with camping and entering a park after hours and was released without needing to post bail. He pleaded not guilty and is scheduled for a hearing in April.

Stephen Schnably, a University of Miami law professor who specializes in homelessness, said it’s not clear whether Miami Beach police are fully complying with the camping ordinance, which states that homeless people must be given an opportunity to immediately enter a shelter before they are arrested.

“It’s inconsistent to not expressly tell them, ‘We have shelter that is immediately available.’ If [police] don’t tell them that, how is someone supposed to make a voluntary decision?” Schnably said. “It’s not a meaningful choice if you don’t know what the options are.”

Others have faced harsher outcomes. Footage from bond hearings in several camping cases shows prosecutors employed by the city — part of a program whereby the city pursues convictions for “quality of life” offenses like public drinking and trespassing that often involve homeless defendants — pressing a judge to set cash bail in some cases.

In one case, the city’s advocacy led a judge to impose $1,000 bail for a homeless man arrested for sleeping on the beach, over the objection of a public defender who disputed a police report that said the man refused assistance and shelter. (The Herald in late January requested body-cam footage of the arrest, but it has not been released.)

The man spent more than two months in jail before he pleaded guilty in early February to entering a park after hours and was assessed $258 in fines, court records show. The camping charge was dropped.

“What you have before you is a person that was lying in a sleeping bag on the beach,” Renee Gordon, a Miami-Dade public defender representing the man, said at a Nov. 30 bond hearing. “What has he done, and what does the court have before him? A person who was sleeping and wants help.”

A city prosecutor, Woody Clermont, noted that the man has a criminal history, including an open container violation last year and convictions elsewhere in Florida in 2016 for battery and resisting an officer with violence.

“I just want to be clear, for the record, that if anything happens at this point afterwards where his release results in harm to other citizens, that we were warned,” Clermont said.

The man has not been arrested in Miami-Dade since his release, according to county records.

Gordon and representatives for the Miami-Dade Public Defender’s Office declined to comment or make their clients available for this story. The Herald was unable to reach the men who were arrested.

City reminds officers of the law

In response to questions from the Herald, Miami Beach spokesperson Matt Kenny shared a memo that was issued by the city’s police legal advisers in late January, reminding officers to ensure that people are offered “immediate shelter” before a camping arrest is made.

“It is also essential that the offer of immediate shelter (and not ‘services,’ ‘homeless outreach,’ or ‘homeless assistance,’ etc.) is documented in the arrest affidavit and any other associated reports,” the Jan. 24 memo said.

The reminder was issued after a public defender argued at bond hearings that the language used in arrest reports was insufficient, Kenny said, though he noted the city disagreed. The Herald first inquired in December about the language used in camping arrest reports but did not receive a response.

Kenny said the city does not have data on how many people have been placed in shelter as a result of the ordinance but said “we can anecdotally confirm that individuals have accepted placement both in response to a field interview and/or in lieu of arrest.”

As part of a “pilot program” in which the city is extending a second-chance offer to place people in shelter during bond hearings the day after they are arrested for camping, four people said they wanted shelter placement, Kenny said. In exchange, he said, the city prosecutor agreed to advocate for their immediate release and to have city staff transport them to the shelter.

Only one of those cases actually resulted in a shelter placement. A man was transported to Camillus House, a shelter in Miami, and remains there today, according to Kenny. His charges remain pending, but “we anticipate that his charges will be dismissed” as he works with the city on a housing plan, Kenny said.

Two others accepted shelter at their initial court appearances but “refused” to enter Camillus House after being released, Kenny said. In another case, a man said in court that he wanted shelter but was transported to a hospital by jail staff before his release.

While there are no homeless shelters in Miami Beach, the city has contracts for more than 70 beds at various shelters in Miami, including Salvation Army, Miami Rescue Mission, Camillus House and Lotus House. Miami Beach police also have three beds set aside at Salvation Army where they can bring people after hours.

Police Chief Wayne Jones said at a meeting last month that, as of Feb. 21, more than 40% of arrests citywide this year had been of homeless people, up from about one-third in the prior two years and one-quarter in 2021. But the city says it isn’t targeting the homeless.

“It will always be the policy of this city that no unhoused person will ever be arrested unless they have committed a crime that any other housed person would be subject to arrest for the same act,” Kenny said.

‘Tough love’

In October, the Miami Beach City Commission passed the revised camping ordinance in a 4-3 vote, removing a requirement for police to give people a chance to move somewhere else to avoid being arrested.

The ordinance now says people “must be given an opportunity to enter a homeless shelter or similar facility within Miami-Dade County, if available to that person” or to accept “other available governmental assistance” that would result in immediate housing.

Meiner said at last week’s press conference with the governor that it was “compassionate legislation.”

“It gives our law enforcement the tools to try to get them the help that they need, offer them the shelter. And if they refuse, the officer has the discretion to make the arrest,” Meiner said. “Sometimes it’s a little bit of tough love, but it’s necessary tough love.”

Police made about 20 arrests under the revised ordinance in late November and early December, most of which involved people sleeping on the sand in South Beach. Most of them were also hit with charges of entering a park after hours. Beaches in the city are closed from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m., and most parks close after sunset.

At a City Commission meeting last month, Jones said 25 people have been charged with camping since the revised ordinance took effect.

READ MORE: Miami Beach police begin arresting homeless people under stricter ‘camping’ ban

The city’s approach represents an escalation of longstanding efforts to crack down on misdemeanor crimes and city ordinance violations that often implicate homeless people. At the February commission meeting, Commissioner David Suarez presented a slideshow of photos of homeless people on the street and pressed Jones to have his officers enforce the camping ordinance more strictly.

“At a certain point, I don’t want the pictures you saw to be everywhere in Miami Beach,” Suarez said.

Arrests under the ordinance have declined since late last year, perhaps in part because of its legal complexities. At the commission meeting last month, Jones, the police chief, said enforcing the camping ban is “a bit tedious” because of the requirement to offer shelter, unlike charging people for simply being on the beach or in a park after hours. Records from the city’s municipal prosecution team show police have charged more than 120 people with being in a park after hours since 2022.

Kenny, the city spokesperson, said officers have not been told to stop enforcing the camping ordinance.

Miami Beach police regularly charge homeless people with other offenses, most commonly open container violations, records show. At least one homeless Miami Beach man has been arrested more than 70 times since 2017, according to Miami-Dade jail booking records. More than two dozen of those cases involved open container laws.

In January, the Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust reported that there were 154 unsheltered homeless people in Miami Beach in its overnight count, up slightly from 152 in August but down from 235 last January. Suarez said he didn’t believe those numbers.

“I have two eyes. I can see that it’s only getting worse,” he said at the February meeting.

Several elected officials emphasized that the camping ordinance is meant to help homeless people. Those who will benefit most, Suarez said, “are the homeless individuals who are being encouraged to use the homeless services that we offer.”

Commissioner Alex Fernandez, who proposed a separate ordinance last month that subjects people to arrest for blocking sidewalks and streets, called the camping law “a tool to help individuals compassionately get the much-needed services that they deserve.”

“If they decline those services, they should be arrested, from my perspective,” Fernandez said.

David Peery, who leads the nonprofit Miami Coalition to Advance Racial Equity and was a plaintiff in the landmark Pottinger case on homelessness in the city of Miami, said he rejects the idea that people who decline shelter placement or any services short of permanent housing should be criminalized.

Many homeless people say shelters are worse than being on the streets because of experiences with violence and drugs or concerns about following strict shelter rules. And even after entering a temporary shelter, finding stable, affordable housing in South Florida is a daunting task.

“The only service that truly affects homelessness are homes,” Peery said. “If somebody refuses shelter, it in no way says they want to be on the streets. It simply says that, because shelters present so many problems for them, they’d rather take their chances on the streets.”

‘Helping people find success’

Officials have highlighted the city’s investment in homeless services — including a police homeless resource unit and $2.7 million in this year’s budget that goes toward a team of caseworkers and a walk-in center for the homeless population — while touting the camping ordinance as an additional “tool” to get people off the street.

Alba Tarre, who leads the city’s Office of Housing and Community Services, said in an interview that, typically, about three or four beds are available for people seeking shelter through her office. Once someone is placed in a shelter through the city, they can stay there for months if they follow a “care plan” devised with city caseworkers.

Getting people into a shelter isn’t always easy, Tarre said. Some beds are reserved for men and others are for women. If only a top bunk is available, people with physical disabilities may not be able to access it. And people may be barred from particular facilities or wary of a shelter where they had a bad past experience.

Tarre said the city seeks to develop relationships with unhoused people through an outreach team that walks the streets and speaks with them, learning what type of medical help they may need, whether they have family members they could reunite with and if they may want to enter a shelter.

“We believe in constant engagement and rapport-building,” Tarre said. “Our job is helping people find success, whatever that means for them.”

Kenny, the city spokesperson, said officers with the police homeless resource unit are typically contacted to assist with shelter placements. They conduct a records check to make sure the person is not a sex offender or someone with a violent history. If it’s after normal business hours, they contact the Salvation Army to ensure the person hasn’t previously been banned from the facility, then transport them to one of the police department’s three beds.

“If all police beds were to ever be filled on a particular night, the city has ample beds in which to house any overflow,” Kenny said. “As best we know, no one who is eligible for a bed has ever been turned away due to availability.”

Schnably, the University of Miami professor, said the interactions between Miami Beach police and homeless people arrested for camping don’t seem to reflect a sensitive approach. People should understand the implications of an offer of shelter before they accept it, he said, including where a bed is located, how long they are allowed to stay and if they need to give up their personal belongings to enter.

The seemingly vague offers of shelter under the Miami Beach ordinance call into question whether the city is genuinely trying to help, Schnably said.

“Clearly, the philosophy of it isn’t really to try to be humane or avoid criminalizing homelessness,” he said. “You kind of wonder whether they just hope people will leave Miami Beach.”