In a deep red state, Oklahoma attorney general embraces policy nuance, shirking party politics

Some months ago, a little-known Oklahoma state school board grabbed national attention with a single vote. It approved what could become the nation’s first public religious charter school.

Oklahoma’s Republican governor and state schools superintendent embraced the idea as the leading edge of the school choice movement, their party’s push to steer taxpayer money to private and religious schools.

But another prominent Republican stood in the way. Attorney General Gentner Drummond sued the board that approved the school. He appeared before the Oklahoma Supreme Court in April to argue why St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School should never be allowed to open.

“If we ordain this church, if this stands, then this court has effectively authorized a state religion,” he warned the court’s nine justices.

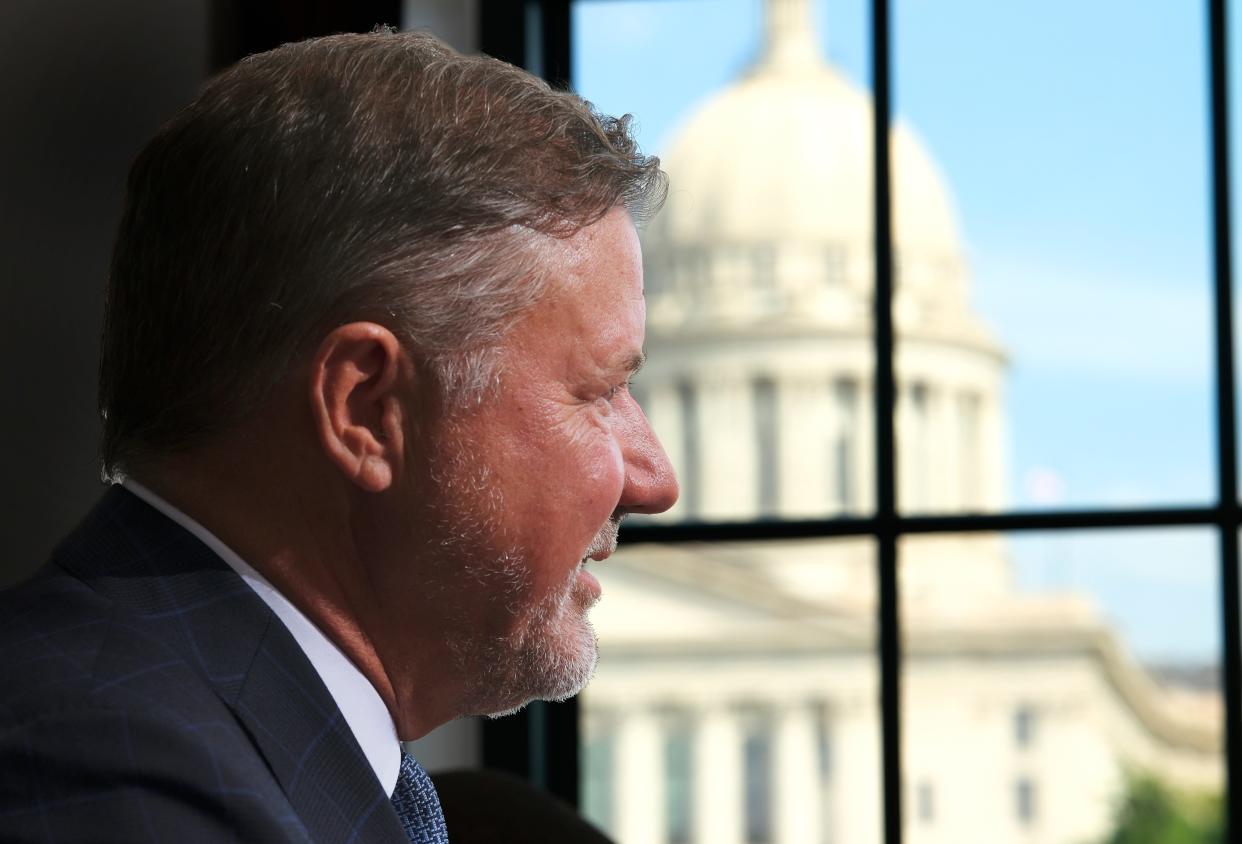

Drummond, a 60-year-old rancher and banker, became Oklahoma’s top legal officer a year and a half ago. Now, almost halfway through his term, many voters have come to view him as a welcome check and balance to the governor’s most controversial positions and, more broadly, to the GOP’s march further right on issues such as religion in schools.

In Drummond’s telling, the law will always trump party politics as long as he is attorney general.

“I think that a fair observer would comment that several of the positions that I've taken would injure me politically in the Republican Party,” he said. “And that’s regrettable, and that’s not my objective to injure myself politically. But I am unabashed in my commitment to the law, irrespective of the cost.”

Yet it’s because of his pushback to some of his party’s more extreme views that his profile has risen as a potential candidate for the state’s highest office. The possibility has also left some people who follow Oklahoma politics wondering who Drummond really is: a conservative unafraid to buck the party line or a politician trying to set himself apart from his most polarizing peers.

“You can’t go rightward from the governor, so he’s sort of left in this middle ground,” said Christine Pappas, who teaches political science and legal studies at East Central University in Ada.

More: Oklahoma Supreme Court appears skeptical of argument that St. Isidore would not be a public school

If Drummond once seemed an unlikely foil to Stitt — like the governor, his family has lived in Oklahoma for generations, he built a career as a successful businessman, and he won a statewide office as a relative political newcomer — he has recently appeared to lean into his anti-Stitt brand.

Drummond has repeatedly challenged the governor’s power in court. He’s also taken aim at some of Stitt’s signature policy positions, including the governor’s claim that Oklahoma is facing an existential crisis because of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling on tribal reservations. Drummond has backed the decision.

Oklahomans have noticed. A poll released in September found more voters trusted the attorney general than the governor to address issues stemming from the ruling.

Drummond’s opposition to St. Isidore has made him stand out on a national level from Stitt and state schools Superintendent Ryan Walters. Critics fear the case could open the door to religious public schools in red states across the U.S.

Drummond emerged as a moderate voice in the fight simply by advocating for such basic principles as the separation of church and state, Pappas said. In turn, Stitt has accused Drummond of ignoring religious freedom.

Drummond denied that tensions have grown between him and the governor. But in recent months, both have seemed content to fuel the mounting drama. In a dispute over a tribal compacting lawsuit, Drummond remarked, “How the governor chooses to interact with the tribes is his prerogative, but he is not free to violate Oklahoma law.” Stitt countered by claiming the attorney general was on a “crusade against the state.”

The two elected officials likely have far more in common than their constant legal feuds might suggest, several political observers said. Both are socially conservative, pro-business Republicans. They have called for tougher enforcement of illegal immigration and defended the state’s abortion bans after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

“Abortion is a huge issue for Republicans,” said Pat McFerron, a Republican political consultant in Oklahoma City, “and I don’t know if there is any difference between Drummond and Stitt on that at all.”

When asked whether any of his resistance to some of Stitt’s stances was driven by political strategy rather than genuine belief, Drummond bristled.

“I'm not a policymaker,” he said. “I am the one who implements and enforces the law. So to the extent the governor and I are aligned, that’s coincidental. To the extent he and I are not aligned, that’s equally coincidental.”

He dismissed the idea of running to succeed Stitt in two years as a distraction, but he stopped short of ruling out a run for governor altogether.

Drummond said he makes decisions at the speed of sound, something he was trained to do as a fighter pilot in the 1991 Gulf War. Some of those decisions may have cost him the chance of ever being elected again by Republican primary voters, he said. Drummond said in his view, he does his job as a nonpartisan, something that he knows frustrates members of his own party.

“The right thing is not always the Republican thing,” he said during an interview last fall.

One move that generated particularly fierce blowback from members of his own party, he said, was his decision to request clemency for death row inmate Richard Glossip because of undisclosed evidence. Glossip had been convicted of killing his former boss in 1997.

Some people saw the attorney general's decision to back a convicted murderer as an attack on prosecutors. Drummond said he considered the case from his perspective as a former defense attorney. Glossip would not have received the death penalty if his lawyers had all the facts known today, Drummond said.

Reflecting on the situation months later, Drummond said he would make the same decision, but perhaps in a different way. “I would probably do it more subtly,” he said.

Drummond has appeared more careful about his opposition to the religious charter school, linking his stance to conservative talking points.

“Today, we’re discussing funding Catholicism,” he said in a statement after he argued the case before Oklahoma’s highest civil court. “Tomorrow we may be forced to fund radical Muslim teachings like Sharia law.”

Drummond described the case weeks later as one of the most consequential issues to go before the Oklahoma Supreme Court in the last decade. He wanted to argue the case himself because of its gravity, he said.

Drummond family ties to Osage County

Long before Drummond made a name for himself in Oklahoma, his family name was well known in Osage County, the northern part of the state where he grew up.

His great-great grandfather, Frederick Drummond, moved to the area in the late 1800s when it was part of Indian Territory. The U.S. had promised the land to the Osage Nation as a reservation. Frederick Drummond traded with Osage citizens and later operated a trading post in the small town of Hominy with his wife, Addie Gentner.

More than 100 years later, their descendants now own huge swaths of Osage County. In addition to Gentner Drummond, another great-great grandchild who ranches is Ladd Drummond. His wife is Ree Drummond, who launched a food and retail empire as The Pioneer Woman.

How the family came to amass so much land goes back to the time depicted in the Oscar-nominated film “Killers of the Flower Moon.” Congress divided up the Osage reservation into individual pieces of land allotted to tribal citizens, ostensibly to make way for Oklahoma to become a state in 1907. Osage citizens also received valuable mineral headrights.

White settlers streamed into the area. They often used state courts to take advantage of Osage citizens. An unknown number of Osage citizens were killed for their land and headrights. Several of the murders were depicted in “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

More: Complicated story behind 'Killers of the Flower Moon' needs to be told, some Osage people say

The Drummond family has never been linked to any of the killings. But it was against this backdrop that the family’s land holdings ballooned, land that had been owned by the Osage Nation and its citizens.

A 2022 investigative podcast produced by Bloomberg raised questions about some of the Drummonds’ business dealings with Osage citizens. The family trading post, which later became a general store, likely overcharged tribal citizens for basic goods, the report said. Some Drummond family members may also have settled debts in exchange for land.

After Frederick Drummond died in 1913, three sons carried on the family name in Osage County. One was best known as a rancher, one as a banker and one as an attorney, all vocations Gentner Drummond would later pursue.

He has preserved his family history in other ways, as well. He owns the mostly empty building that once held his family’s store in downtown Hominy. He also lives on a ranch that has passed down through his family for generations.

Drummond claims, though, to have never accepted any inheritance, in part because of the history of his family’s land. He said he built his 23,000-acre ranch piece by piece, starting when he was a teenager.

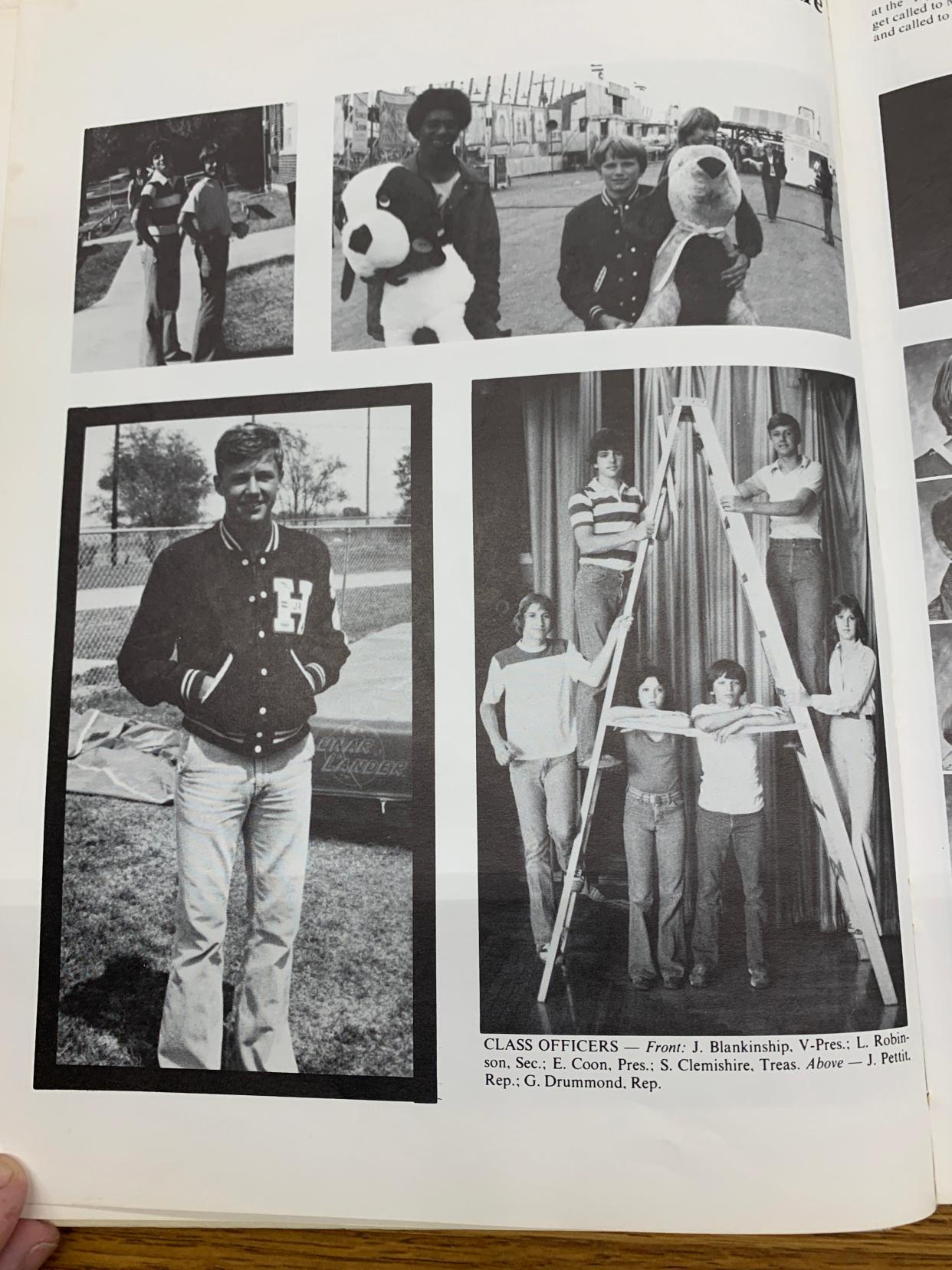

At Hominy High School, Drummond was better known as a leader and athlete. He was class president his senior year, according to the school’s 1981 yearbook.

“Gentner enjoys dating, athletics, pleasing his friends and parents, scouting (Boy Scouts and Explorers), playing the piano, guitar, tuba and baritone, getting out-of-doors and being alone to contemplate,” a yearbook caption said.

Like many Drummonds before him, he went on to Oklahoma State University. He later joined the Air Force. He got his first taste of national attention and statewide acclaim in 1991, after he was among the first pilots to fly in a combat mission in the Persian Gulf War. He was lauded as a local hero, and accounts of his actions were printed in newspapers across the state.

He started to practice law in Tulsa in the mid-1990s after he graduated from Georgetown University’s law school. Some of his cases gained widespread attention, such as his time spent defending his hometown’s 2004 Citizen of the Year, who had been charged with killing a waitress.

He also represented a controversial Tulsa charter school in 2002. Its links to a local church generated some of the same questions Drummond is facing today about the separation of church and state. Drummond said he was assured the school, Pentagon Academy, would not have religious instruction. He drew a line between its plans and those for St. Isidore, the Catholic charter school he is now trying to block from opening.

“I think they were unabashed with their declaration that it would be Catholic in every way, from employment regulations to instruction,” Drummond said. “And you can’t square that with the Oklahoma Constitution, nor the U.S. Constitution.”

Some critics of Drummond’s work as a lawyer started speaking out after he launched his first run for attorney general in 2018. A cousin claimed he advised her to lie so her 2012 divorce proceedings could occur in rural Osage County rather than in Oklahoma County. His campaign dismissed the claim as politically motivated.

Drummond built up other businesses apart from his ranch and legal practice, including a chain of cellphone stores and Blue Sky Bank, a $1.1 billion community bank based in Pawhuska.

He drew scrutiny in 2022 after federal records revealed his bank had processed $1.7 million in Paycheck Protection Program loans that went to his other businesses. The bank generated about $70,000 in processing fees and interest from the loans, The Oklahoman reported at the time.

He funded his campaigns largely with his own money, loaning himself a collective $4.2 million in efforts to get elected. His first campaign for attorney general ended in defeat in 2018. The winner, Mike Hunter, stepped down in 2021, creating an opening for Stitt to appoint a replacement. The governor bypassed Drummond and went with John O’Connor, who backed his opposition to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on tribal reservations.

Drummond defeated O’Connor in the Republican primary race the next year. He quickly started meeting with representatives of Oklahoma’s 38 federally recognized tribes, estimating that he spent hundreds of hours in negotiations during his first nine months in office.

His approach was not unusual for a state official in Oklahoma, where about one in six residents is Native American, said Kirke Kickingbird, an Oklahoma City attorney who once served as Gov. Frank Keating’s adviser on Native American affairs.

Friction builds among Republican officials in Oklahoma

But Drummond’s actions stood out in the current political climate. Stitt more often spars with tribal leaders in the media instead of meeting with them face-to-face.

The contrast between the two sharpened in July. The attorney general attempted to force the governor to stop defending a federal lawsuit over tribal gaming agreements signed by Stitt. The state Supreme Court had already struck down the deals.

Though Drummond said he respected Stitt, he said he considered the governor’s handling of tribal relations “wrongheaded by 180 degrees.” The attorney general has not always agreed with tribes, however. He sued several Muscogee Nation officials in federal court in February, challenging the tribe’s right to prosecute an Okmulgee County jailer accused of assaulting a tribal police officer.

“I've tried very hard to illustrate to the tribes that not all statewide officials are anti-Native American,” Drummond said.

Drummond to tribal leaders: Oklahoma deserved McGirt ruling because state failed to deliver justice to Native victims

Other disputes have seemingly intensified the friction between the attorney general and other leading Republican figures. The attorney general cast doubt on the roles of several of Stitt’s Cabinet members in February. He issued a binding opinion that concluded the Oklahoma Constitution barred officials from holding more than one office at a time, looking specifically at the roles of Stitt’s transportation secretary, who also led the Oklahoma Department of Transportation and the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority.

Stitt called the legal opinion flawed and joined three of his Cabinet members to sue Drummond.

The attorney general has twice stepped in to dismiss lawsuits launched by Stitt against ClassWallet, a contractor hired by the state to distribute $18 million in pandemic relief funds meant to used for educational purposes. Auditors later questioned more than $1 million of the spending.

Stitt and Walters, who became the governor's education secretary in September 2020, have repeatedly blamed ClassWallet for not monitoring the spending. Drummond has insisted, however, that failed state oversight is to blame.

Walters became Oklahoma’s schools superintendent in 2023 and pushed to instill new rules on schools regarding library books and transgender students. He was elected on campaign promises to rid schools of porn and “woke ideology.” The Oklahoma State Board of Education adopted the rule changes advocated by Walters.

But Drummond issued a binding opinion in April rejecting the rules as moot, because he concluded they were passed improperly.

“Whether I agree or disagree with any particular rule in question is irrelevant if the board does not have the proper authority to issue those rules,” he later said.

Many believe Walters is a leading candidate alongside Drummond to succeed Stitt in 2026, though neither has announced any intent to run. The field will probably not begin to shape up until after the presidential election in November.

Oklahoma voters care about issues that are quite different from the legal disputes that push Drummond into the news, said Bill Shapard, an Oklahoma City political researcher who also conducts statewide surveys.

“Oklahomans, regardless of Republican or Democrat are going to be more focused on the national issues — immigration, inflation, the price of gas and groceries,” Shapard said.

Republican voters specifically are focused on security issues, said McFerron, another pollster. They are not only concerned about immigration on the national level, but also the crime associated with illegal marijuana grows in Oklahoma. In that respect, Drummond could get a default boost in some voters' minds, because he is Oklahoma’s top law enforcement officer, McFerron said.

Still, the running disconnect between GOP politics and voter concerns makes it hard to see what the future might hold for Drummond or any other leading Republican, Shapard said.

“I think that in Oklahoma, Republicans are right now looking for who is our next leader,” he said. “Is it a Stitt-picked person, or is it Gentner Drummond, or is it someone else completely?”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Gentner Drummond is the Oklahoma AG fighting religion in public schools