Pitman Farms, maker of ‘humane’ Mary’s Chicken brand, among most dangerous for workers

Inside the Pitman Family Farms poultry processing plant, hundreds of mostly Latino immigrants endure dangerous conditions, working long hours to slaughter, clean, cut, grind and package certified organic and free range poultry under the “Mary’s Chicken” brand and others considered ultra high-end and healthy alternatives to regular mainstream birds.

Entering the gray plant, more than half a football field in size, workers’ eyes start to water from the chemicals and lack of ventilation, though not everyone is provided protective goggles, one former employee said. The noise from meat grinders and cutting tools is so loud, workers wear earplugs – when available. Pitman workers are forced to log every minute in the bathroom, and they’re sometimes pressured to work through lunch and overtime, multiple workers contacted by The Fresno Bee said.

And there’s little-to-no training on how to safely wield the sharp, 6-inch, boning knives workers use to process poultry, several employees told The Bee in multiple interviews about working conditions. Workers told state investigators that training was limited to video and “some verbal” instruction.

The grueling work can be dangerous and damaging, state records and interviews reveal. One former employee told The Bee that he still deals with lingering wrist pain from years of hanging live, 30-pound birds on hooks when he worked at the company a decade ago. Another said he feared electrocution when a supervisor asked him to clean a pool of chicken blood on the floor of a room full of electrical cords. Another has had multiple surgeries after her hand got stuck in an industrial meat grinder, she said.

“It was the most brutal work I’ve ever done,” said former employee Moises Hernandez, who worked the graveyard shift for two years while he attended Fresno State during the day in the mid-2010s.

Poultry processing is one of the most dangerous jobs in the country due to the risk of amputations from heavy machinery, burns from hazardous chemicals and chronic injuries from repetitive motion, according to OSHA, the federal agency that enforces workplace safety regulations.

Workers at the Pitman processing plant, in the central San Joaquin Valley city of Sanger, told The Bee that they choose to endure potential danger and pain because starting at around $18 an hour — two dollars more than California’s minimum wage — the pay at Pitman is better than other local agricultural jobs in the area, especially when combined with overtime.

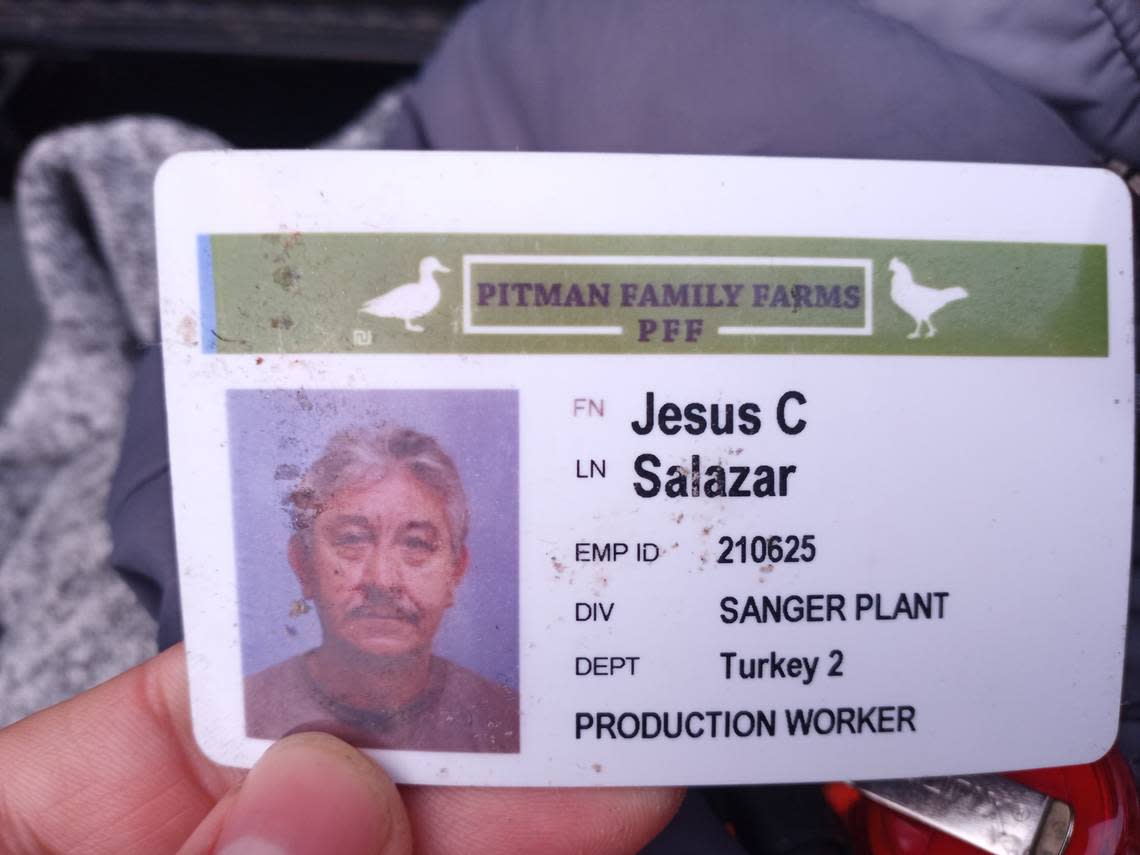

It’s that drive for a better life that led 66-year old Jesus Salazar to a gruesome end after he fell into a poultry waste pit at the company’s processing plant last spring and drowned in an unthinkable way. Police photos of the scene show his green helmet resting on top of a sludge-like mix of chicken feathers, remains, waste, fat and water in the pit where he died.

Salazar’s death was one of three at Pitman’s California-based operations, which includes the Sanger plant, a network of ranches, and an industrial feed mill, over the past decade.

Worker deaths at poultry processing plants are relatively rare: Federal fatality data show that there were 14 poultry processing deaths nationwide in 2021 and eight in 2022.

A Fresno Bee investigation of Pitman workplace conditions based on interviews with current and former employees and an exhaustive review of hundreds of pages of state and federal court and regulatory documents and law enforcement reports revealed a dangerous grueling workplace with multiple serious safety violations and more than $140,000 in settled fines from Cal/OSHA, the state’s main enforcement branch for workplace safety regulations.

Between 2017 to 2022, the company also self-reported more than 400 injuries at just its processing plant in Sanger to federal health and safety authorities, according to OSHA reports. A Fresno Bee analysis of federal self-reported injury data from poultry processing plants found that Pitman had among the highest self-reported injury rates in the nation.

Some of The Bee’s other findings include:

The other two Pitman worker fatalities resulted from an electrocution and tractor accident. In a fourth death, a Pitman employee in a tractor hit and killed a truck driver from another company who was on the grounds of a Pitman facility.

At least 10 workers suffered life-altering injuries on the job, including electrocutions, head trauma, broken bones and amputations, based on worker interviews and government injury reports.

Cal/OSHA provided detailed documents from six closed investigations involving worker safety violations at Pitman. In three of the investigations, inspectors found that a lack of proper training on industrial equipment was a factor, such as not ensuring employees understood specific safety training for operating heavy machinery.

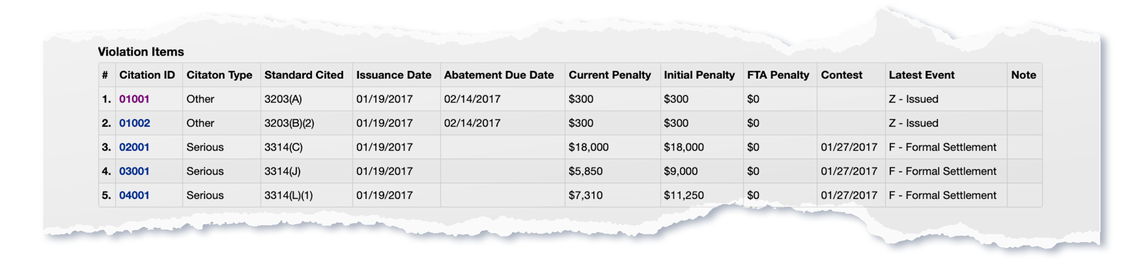

A separate analysis of OSHA closed case data from 2015 to 2022 found that unplanned inspections – those related to accidents, complaints, and whistleblowers – resulted in more than $140,000 in settled fines for violating 50 health and safety rules, including a dozen “serious” violations.

Employers have the right to contest any citation or violation. In many instances, the company appealed and contested the state’s initial alleged violations and fines, oftentimes successfully negotiating lower fines or formal settlements. When an employer settles with the state, they’re not considered to be at fault or admitting to any wrongdoing.

The state’s investigation into Salazar’s death is still open, and the company recently contested the four serious violations and $56,250 in citations related to his death.

The Bee made several attempts to contact Pitman Family Farms for comment on this story through phone calls, voicemails and email. The Bee also visited the company’s processing plant in Sanger and left a message with security staff at the front gate in May. Those requests for comment went unanswered.

In November, David Pitman, a member of the ownership family, declined to comment on this story on the company’s behalf in a phone call with The Bee.

Pitman Family Farms’ policy is to “maintain a safe and healthy work environment for each employee,” according to a 2020 company injury and illness prevention program booklet.

Poultry industry leaders say food safety is a priority, especially in California, where the consumer culture wants fresh, organic food. Pitman adheres to various animal welfare and certified humane standards in the raising and handling of its chickens, sold under the popular brand, Mary’s Chicken.

“We in California hold our companies to a very high standard,” said Bill Mattos, president of the California Poultry Federation industry advocacy group, of which Pitman Family Farms is a member, in a November interview with The Bee. “We’re under a microscope here.”

Mattos said that poultry work is “pretty intense,” but that major processors offer ample training.

“None of the plants want to get in trouble or want their people to lose an arm or lose a leg or whatever,” Mattos said. “So I think they’ve learned to train people pretty aggressively.”

But for Alice Berliner, the director of the Worker Health & Safety Program at the UC Merced Community and Labor Center, there’s “a clear contradiction” when companies build their brands on humane animal treatment but have safety violations for their workers.

“It’s clear that there’s not a value placed on the human lives of the workers,” said Berliner, who was giving her opinion, in general, of the industry.

A horrible way to die

The Pitman family has raised poultry since 1954.

Today, Pitman Family Farms is known for producing high-quality chickens, ducks and Thanksgiving turkeys. Chefs, restaurants and social media influencers across the state proudly tout Mary’s Chickens – the line of organic, free-range chickens named for the company’s late president – on their locally sourced, farm-to-table menus and social media pages. Whole Foods Market, known for its high-end and organic offerings, also sells Pitman products.

Mattos said Pitman Family Farms is one of the fastest growing poultry companies in the San Joaquin Valley.

Powering that growth and the estimated multi-million-dollar business are 1,300 to 1,500 workers at its Sanger-based processing plant.

The Sanger plant is where Salazar was working when he died.

Originally from the Mexican state of Michoacán, Salazar worked for years in hotels in San Jose before coming to the Valley and working at Pitman Family Farms. Salazar’s family told The Bee he was a “very hard worker” and had been at the processing plant for about two years.

He had been picking up extra shifts to save up for a family vacation when he died.

On the morning of his death, Salazar and a coworker were assigned to clean the area around the waste pit and also check interior pipes for leaks. The waste pit is a rectangular structure 14 feet wide, 18 feet long and up to 25 feet deep, far deeper than most any swimming pool. It contained all of the chicken parts that aren’t packaged for sale: a mixture of chicken feathers, bones, waste, fat and water.

In the pit, water is separated from the chicken waste before it is sent back to the city to be treated. Around the opening of the pit, police photos show a catwalk caked in feathers and fat. One side of the pit does not appear to have a protective railing.

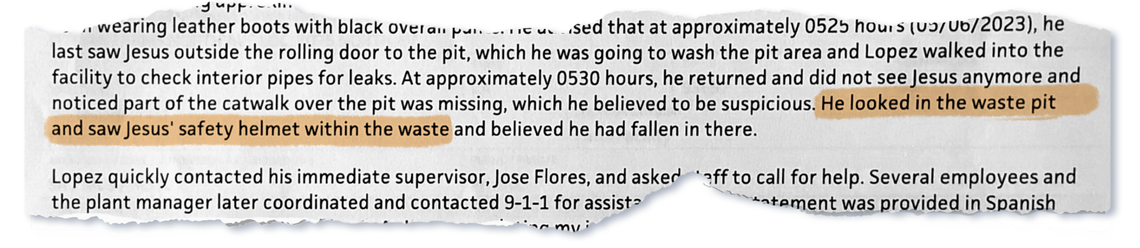

Around 5:25 am, Salazar was outside of the door to the waste pit while his coworker went to check on the pipes, according to a police report of the incident. A few minutes later, the other worker returned, but he did not see Salazar. It’s not immediately clear how Salazar ended up in the pit. There were no direct witnesses to the incident, Cal/OSHA noted in its investigation record.

“He looked into the waste pit and saw Jesus’ safety helmet within the waste,” a police report noted. Later, a police officer who arrived at the scene said he saw in the pit, “a set of boots with the toes pointed upwards.” A dive and rescue team extracted his body, and he was pronounced dead at the scene.

The Fresno County Coroner’s Office told The Bee in May that Salazar’s cause of death was drowning.

Sanger police on the scene wouldn’t approach the pit because of the risk of falling in. “Sanger fire crews warned me of how slippery it was due to the mixture of water, animal fat and feathers and other wastes,” reported one officer in the police report.

Coworkers remembered Salazar as a warm colleague who cracked jokes and would offer food from his lunch box. In May, Salazar’s grieving family told The Bee that he was a loving and generous man who loved his grand kids and mariachi music. They did not want to comment on the record about Salazar’s death, but said they hoped no one else gets injured.

Karina Torres, a former Pitman employee and friend of Salazar, said his death was devastating.

“A family lost a dad, a brother, a grandfather, an uncle,” she said in Spanish.

Two other employees have died in recent years while on the job for Pitman.

On July 25, 2019, a worker at the company’s Chowchilla-based operations was using a forklift to move a chicken feed tank. The forklift came in contact with an overhead high-voltage power line, which electrocuted and killed the worker. Cal/OSHA issued more than $73,000 for five different serious and repeat citations related to the incident. According to the online inspection record, Pitman and the state are engaged in a settlement process. As of February, per the online record, the case has not yet closed.

In 2015, another worker died from crushing injuries when he was “traveling too fast” in a forklift, causing it to overturn. The company entered a formal settlement agreement and paid the state $4,500.

Cal/OSHA also investigated Pitman in 2018, after 62-year-old Lowell Beecher, a truck driver employed by feed manufacturing company JD Heiskell, was crushed by a Pitman tractor that was moving chicken feed at a grain mill in Hanford. The truck driver ultimately died from his injuries. His family sued Pitman Family Farms and was awarded a $4 million settlement.

“We are deeply saddened by Mr. Beecher’s passing, and our hearts go out to his family,” lawyers representing Pitman wrote to Cal/OSHA later that year.

Pitman workers injured by industrial meat grinder

Workers and state health and safety inspection reports indicate that a lack of thorough training has in part contributed to some injuries at Pitman Family Farms.

In May 2020, Torres, 40, a former Pitman processing plant employee, was working with an industrial meat “grinder” used to extract leftover meat from animal carcasses (Pitman uses meat separator machines or mechanically separated chicken machines in its processing plant, according to Cal/OSHA reports). She worked at the company for seven years and at many different jobs — from hanging and cutting chickens to deboning and packaging them. This was the first time she had worked with the industrial grinder, she said.

Torres was placing a chicken in the machine while it was turned off. Another worker turned on the machine with Torres’ hand still in it. Her right index finger “broke in three pieces.”

A state workers’ compensation case file says that Torres sustained injuries to her back, neck, wrist, index finger and arm, which she said was caused by the force of jerking her hand from the machine. She’s had three surgeries related to the incident, so far, she said. Torres left her job last fall as part of the terms of her workers’ compensation settlement and is still looking for work.

“My children eat from the work I do with my hands,” she said.

Torres said her hand now swells up from manual labor, and she has trouble holding everyday items at home due to the nerve damage. “I drop plates. I try to hold three to four plates, and I can’t.”

In October 2016, two employees were fixing a meat separating machine. One of them turned the machine on to test it, and a tool they were using spun and struck the worker in the head. The worker suffered a head trauma and has had two brain surgeries, as a result, according to Cal/OSHA inspection notes.

A processing manager told a state inspector that the workers were “verbally trained on the do’s and don’ts of the machine” but added that more training could have helped prevent the accident, according to a Cal/OSHA report.

Because of the meat grinder incident, Cal/OSHA cited Pitman Family Farms $38,850 and said the company failed to ensure workers performed necessary safety procedures when operating heavy equipment. Investigators on the case also said Pitman failed to provide effective safety training to employees prior to starting new job tasks.

Pitman appealed the decision, saying the employees were trained and that the injury was caused by “distractions by other employees in the area.” The company settled with the state for $31,760, meaning that it was not found to be at fault for the incident.

Training, procedures on paper versus reality

Rotating workers like Torres among different tasks within the plant, OSHA says, is supposed to be a way to prevent ergonomic injuries, such as carpal tunnel syndrome or muscle strains caused by repeated motion and workplace setup.

At Pitman Family Farms, employees are to receive safety training and “be advised of any new hazards” for any new assignments, according to the company’s injury and illness prevention policy, a type of written safety program and guide California companies are required to provide employees.

The company also holds regular safety training, onsite safety meetings and routine safety audits conducted on the worksite, attorney James B. Betts of Betts & Rubin wrote to Cal/OSHA’s Fresno District Manager in a July 19, 2018, letter.

In many instances, Pitman provided the state with documentation that employees had signed attendance for training meetings as well as proof that employees completed safety training tests on safely handling heavy machinery and for tractor-driving.

But in three of six Cal/OSHA initial inspection reports reviewed by The Bee, inspectors found the company had failed to provide adequate training or evidence of training related to worker injuries. (The company wasn’t considered to be at fault when it settled with the state on these cases.)

Workers told Cal/OSHA investigators that training at Pitman Family Farms is usually provided verbally, through pamphlets and “some video,” according to one inspection report. But workers interviewed by The Bee said the training isn’t enough.

“They say they give you training, but it’s not true,” said Torres, the injured former employee. “They don’t teach you how to cut the chicken or how to sharpen your knives or scissors.”

Workers end up training each other on the job. “You watch your colleague who tells you, ‘You need to do it like this, not like that. Hold the chicken like this,’ ” she said.

‘Folks are getting hurt all the time’

Hernandez, the former employee who worked the night shift while in college, said he did everything from sanitation to live-hanging to de-feathering to rendering, a process that involves extracting “guts” from the chicken to sell for use in products like cat and dog food.

A decade later, his left wrist still flares up in pain from his days hanging chickens. “I’m gonna be living with that for the rest of my life,” he said. One thing stands out to Hernandez about his time working at Pitman: “Folks are getting hurt all the time.”

To better understand just how many people are injured at Pitman Family Farms every year, The Bee analyzed the company’s self-reported injury data that OSHA requires large employers across the nation to report every year.

According to a Bee analysis, between 2017 to 2022, Pitman had higher rates of injuries compared to other similar sized processing plants in the Valley, or 29.4 injuries for every 100 employees. (This analysis does not include data for Pitman Family Farms in 2018, as OSHA doesn’t have any data on file for the company that year.)

By comparison, the three Foster Poultry Farms plants in the Valley had lower self-reported injury rates, at 23.9 injuries per 100 employees at the Livingston plant; 20 injuries per 100 employees at the Fresno Belgravia plant; and 10.2 injuries per 100 employees at the Fresno Cherry Avenue plant.

The data doesn’t paint a complete picture, however.

A reported injury does not mean the company was responsible or had any health or safety violations. “It would be a mistake to say establishments with the highest rates in these files are the ‘most dangerous’ or ‘worst’ establishments in the nation” based on this data, OSHA says.

Industry leaders say that injuries and illness in American poultry plants have been on the decline for decades. Injury rates have declined over 80% in the prior 25 years, according to a 2020 National Chicken Council analysis of federal data. But injury and illness rates “sharply increased” in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, as poultry plants locally and nationwide experienced large outbreaks and deaths.

Poultry companies not complying with laws

Labor experts at UC Merced say more needs to be done to ensure enforcement of, and compliance with, existing labor laws.

Speaking of the industry in general, Berliner of UC Merced said, “there are laws in place, and there are employers that are clearly breaking the law in service of making a profit.”

In a November 2023 analysis UC Merced researchers found that the Central Valley accounts for nearly half, or 42%, of the state’s animal slaughtering and processing industry jobs, despite only accounting for about 11% of the state’s population. At the same time, the Valley has one of the highest rates of unplanned Cal/OSHA inspections – those that aren’t planned ahead of time and are responses to an accident, complaint or whistleblower report. Despite this, the region has the second-lowest rate of violations per inspection. This suggests, researchers concluded, “a lack of agency enforcement and business compliance.”

Asked about the study, Cal/OSHA spokesperson Derek Moore said the department recognizes that more resources are needed in the Central Valley. In August, the agency announced it’s expanding its presence in Fresno and the surrounding area so inspectors can respond quicker and more frequently in the Central Valley.

Torres, the former Pitman employee, has trouble accepting that the company was cited for only $56,250 related to the drowning death of her friend Salazar.

“Bien poquito fue una vida,” she said. “How little his life was worth.”