The dark and the light: A history of solar eclipses in Northeast Ohio

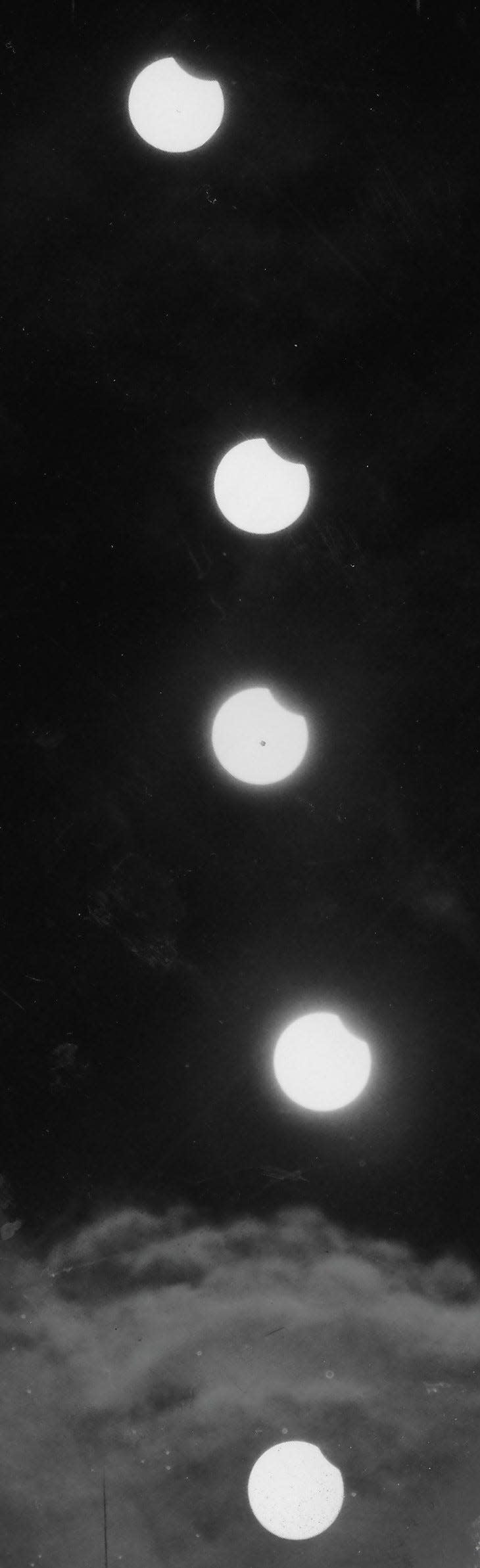

If the weather cooperates, the astronomical event April 8 could eclipse anything ever seen in Northeast Ohio.

The last total solar eclipse visible here was in 1806. Over the past 218 years, there have been at least three annular eclipses — the ones that create a “ring of fire” effect as the moon obstructs the sun — and more than a dozen partial eclipses of varying clarity.

There have been moments of abject terror, ethereal beauty, scientific wonder and total obliviousness.

And there have been clouds. So many darned clouds.

The total eclipse of 1806

Sadly, the local history of solar eclipses begins with a murder.

It was 1806 — only three years after Ohio had become a state. Canton was only a year old and Akron was 19 years away from being founded.

Hinckley Township was a dense forest in Medina County. Wyandot and Seneca American Indians still lived in the region, but white settlers were arriving in droves from the east.

That May, a Wyandot woman told her tribe that a great darkness would soon fall over the land. It’s not known how she determined this. Was she a scientific genius? Did she overhear a settler?

Regardless, the Native Americans accused her of practicing witchcraft.

“Her prophecy caused alarm among the tribe, and a council was called,” Hinckley expert Charles Neil wrote in “History of Medina County and Ohio,” a book published in 1881. “It was decided that she should suffer death by strangulation by having invoked the powers of the evil one.”

The men marched “the witch” through the woods and hanged her from a large tree that had fallen across the Rocky River near the Granger Township line.

“The body was left swinging to the tree, and remained there as a warning, and as a carrion for the vultures to feed upon, until it finally dropped into the river below,” Neil wrote.

A few weeks passed. Life returned to normal in the woods of Hinckley until a great darkness fell over the land. The woman had been right. The sun began to disappear about 11 a.m. June 16, 1806.

Truman Gilbert Sr., newly arrived from Connecticut with his wife and eight children, was building a house in Portage County’s Palmyra Township when the eclipse began.

“When Truman Gilbert was raising his house in 1806, and was being assisted by the neighbors, as usual, and some Indians, an eclipse of the sun occurred, which badly frightened the latter,” Robert C. Brown and J.E. Norris wrote in “The History of Portage County” (1885). “They left the work, got out their bows and arrows and began firing their arrows up into the heavens in the direction of the slowly darkening sun, to scare off the evil spirit.”

Hudson pioneer Christian Cackler (1791-1878), who arrived here in 1804 from Pennsylvania, was 15 years old when the blackout occurred. In his 1870s memoir, “Recollections of an Old Settler,” he blamed that year’s ruined crops on the celestial phenomenon.

“The day of the great eclipse was a beautiful, warm day; we were hoeing corn the second time, with only shirts and pants on, but, after the eclipse was off, the weather was so much colder that we had to put on our vests and coats to work in,” he wrote. “There were frosts every month that summer; no corn got ripe, and the next spring we had to send to the Ohio River for seed corn to plant.”

Fear of Judgment Day

An annular eclipse in June 1811 caused fright among Ohio settlers, including Nimishillen Township resident Julia Mathias, the wife of Daniel Mathias.

“Mrs. Mathias was away from home on that day on a visit to a neighbor,” Herbert T.O. Blue wrote in “History of Stark County, Ohio” (1928). “On her return it suddenly began to grow dark, although the sun had just begun shining brightly. It was soon so dark that she was unable to see the path and she was compelled to stop until darkness passed away. She was much frightened and supposed the world had come to an end.”

She wasn’t alone in that belief.

Eli Sowers, 14, who had moved with his family from Maryland, was busy helping some men shingle a house on Market Street in Canton when the world blackened. Stars appeared in the sky. The temperature dropped. Songbirds stopped chirping and chickens returned to their roosts.

The workers thought Judgment Day had arrived.

“The sun gradually disappeared, darkness soon enveloped everything about them, and the men, one and all, precipitately abandoned the roof with the impression (bred of the want of knowledge and considerable superstition) that the world was coming to an end, or that some other dreadful calamity was immediately impending,” William Henry Perrin noted in “History of Stark County: With an Outline Sketch of Ohio” (1881). “The sun, however, soon brightened up again and the world still stands.”

Gazing through smoked glass

By the time the next annular eclipse arrived Sept. 18, 1838, Ohio residents were no longer being caught by surprise. Astronomers accurately predicted the event from 2:30 to 5:15 p.m. Residents used smoked glass to gaze into the sky without harming their eyes.

The Maumee Express reported that “the sun passed off very much to the satisfaction of all parties concerned.”

“The ring appeared, through our smoked glass, perfectly regular complete and brilliant,” the newspaper reported. “After the eclipse itself, the most remarkable thing that we observed was the great distinctions of the shadows of all objects within the influence of the sun’s rays. They exceeded everything of the kind we have ever seen.”

Not quite as impressive was a partial eclipse July 29, 1859. The moon covered only about one-eighth of the sun. Cleveland astronomer Jeremiah Cross set up a telescope on Water Street.

“Through it the sun presented a beautiful appearance yesterday,” the Cleveland Daily Leader reported. “The edges (so to speak) of the disc were as sharply defined against the sky as could be drawn with any instrument, being perfectly smooth and round. The edge of the obscuration, on the contrary, was jagged and rough, exhibiting very plainly the inequalities on the surface of the moon.”

‘The hue of death’

Ohio residents also witnessed a partial eclipse from 5 p.m. to sunset Aug. 7, 1869. The Ashtabula Weekly Telegraph called it “a perfect success in the line of exhibitions.”

“During its greatest obscuration, a strange shadowy pallor of light overspread the earth and gave to the countenance the hue of death,” the newspaper reported. “This fact imparted to it a feeling of awe.”

The Fremont Weekly Journal noticed how tree shadows created light shows on the sides of homes: “The rays of the sun, shimmering through the leaves, would cast crescent shaped shadows of the unobscured portion of the sun, upon the house side, until every bright spot where a ray of sunlight rested, appeared a pictured of the eclipse.”

Hundreds of Ravenna residents peered through smoked glass Aug. 11, 1869, to view a partial eclipse from 4:40 to 6 p.m. Temperatures dropped from 77 degrees to 45 degrees as the sun faded.

“At the time when the eclipse was greatest, about five-sixths of the disc of the sun was obscured, and a ghostly darkness prevailed, which lasted a few minutes,” the Portage County Democrat reported. “During the eclipse, a star was plainly seen, apparently a short distance from the sun.”

Not too impressed in Akron

Akron citizens used dark-colored spectacles and smoked glass to observe the sky March 16, 1885. The celestial event began at 2 p.m. and lasted for most of the afternoon, although the Summit County Beacon reported “the eclipse was only partial, the upper portion of the sun’s disc being scalloped out by the shadow.”

The Beacon Journal reported “a sensible diminution in the sun’s light” from 8 to 10 a.m.

“It possessed none of the especially attractive features of a total eclipse for either astronomers or unskilled observers, but careful observations of the times of beginning at different stations enabled still further revision of the tables of the moon’s motion to be made,” the article noted.

Also disappointing was the early eclipse Aug. 30, 1905. It peaked at 6 a.m. in Akron, but heavy clouds blotted out the sun and moon.

“The eclipse of the sun this morning doubtless got many people out of bed who had not seen a sunrise in many years and who probably will not see another in as long a time,” the Beacon Journal noted.

Thousands of Akron residents witnessed a partial eclipse June 29, 1908, which began about 8:30 a.m. and peaked around 10, making the sun look like a crescent moon.

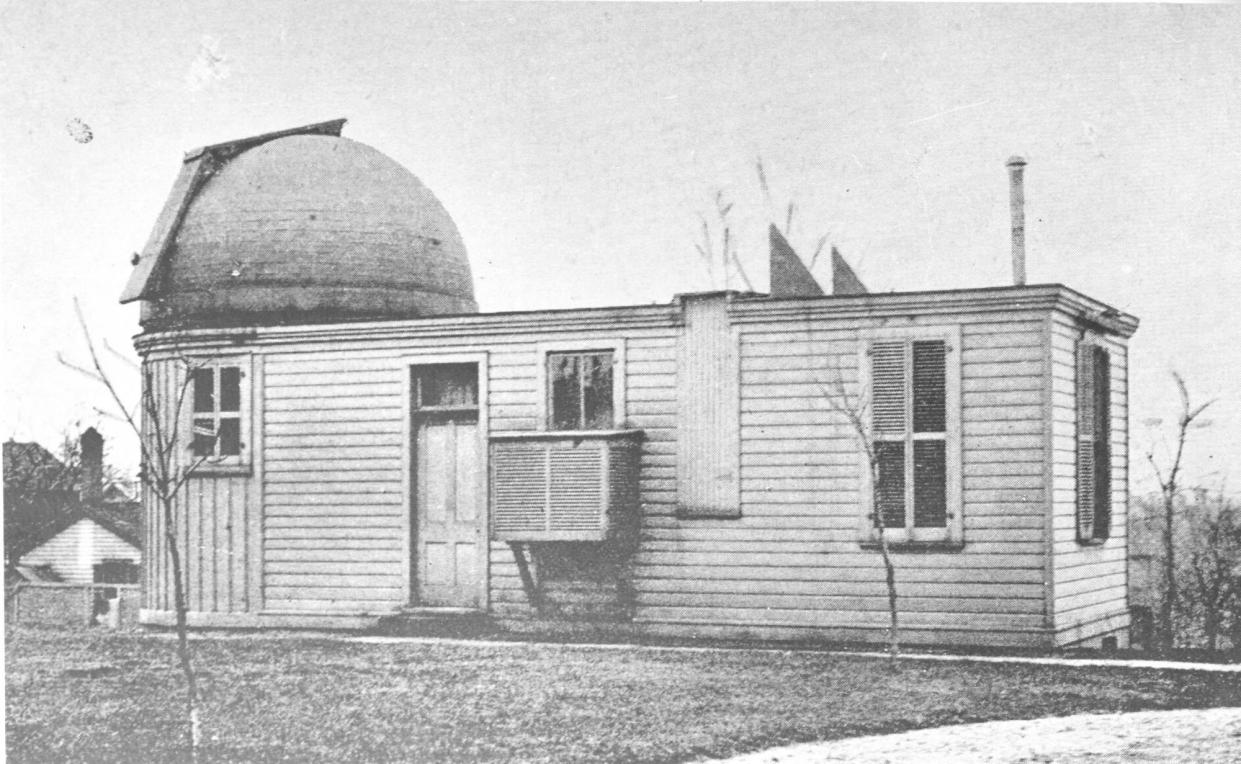

Math professor Paul Biefeld filled Buchtel College Observatory with curious spectators. “The professor used the four and a half inch telescope in the dome of the observatory to throw the image of the sun on a white screen where it could be observed by a roomful of people at the same time,” the Beacon Journal reported.

The partial eclipses of June 8, 1918, Nov. 10, 1920, and Sept. 10, 1923, barely registered here, even though University of Akron Professor H.V. Egbert tried to make them sexy, noting: “Phoebus Apollo and Diana once again meet in fond embrace, a lovers’ kiss of but two short hours.”

“To the superstitious in former days, and the ignorant now, the eclipse of the sun has always been regarded as an omen of evil,” Egbert lamented. “However, no significance is attached to the event in modern days, and even the loss of sunlight occasioned by the happening is scarcely noticed.”

Beautiful yet terrifying

That was not the case Jan. 23, 1925. The partial eclipse from 7:54 a.m. to 10:16 a.m. drew awe on a crystal-clear day. As the moon obscured nearly 97% of the sun, the Beacon Journal heralded it as the “greatest astronomical show on earth.”

“A strange, ghastly pall fell over Akron as the clock reached 9 a.m.,” the newspaper reported. “Street lights were turned on, and the pall over the city did create that instinctive feelings of fear, wonder, astonishment and speculations other than the simple astronomical reasons for the eclipse. There was a feeling of dread in the hearts of many Akron citizens as they viewed the spectacle. Supremely beautiful, it was yet terrifying.”

Another big event scheduled for April 7, 1940, was a total bust. Thick clouds and heavy rains spoiled the partial eclipse from 3:41 to 6:11 p.m.

The Beacon newspaper’s sarcastic review: “Some show, wasn’t it?”

Another partial eclipse Sept. 1, 1951, was underway at sunrise and peaked at 7 a.m. with about 90% of the sun covered, but nobody in Akron saw it because of fog and low clouds. Another big disappointment.

Clouds descended again for the partial eclipse July 20, 1963, but at least the sun peeked out occasionally. Beacon Journal reporter Marvin Katz likened the experience to “trying to watch a movie when the woman in the seat ahead of you is wearing a feathered hat.”

More fears of doomsday

Doomsday fears swirled around the partial eclipse of May 9, 1967. An obscure Cleveland astrologer — not an astronomer — predicted that the celestial event would trigger a nuclear war between the United States and China. Rumors circulated of impending riots, shootings and bombings, but nothing transpired, including pretty much the eclipse. The day was mostly cloudy, so few Ohioans noticed the extra darkness from 9:04 to 10:31 a.m.

The three national TV networks beamed the eclipse of March 7, 1970, to millions of television viewers from noon to 2 p.m. That was the safest way to watch.

“Anyone trying to observe the eclipse without adequate eye protection is courting serious eye damage in the form of retinal burns,” U.S. Surgeon General Jesse Steinfeld warned.

Naturally, it was overcast in Ohio. Most people didn’t seem to notice that the sun had been reduced to a thin crescent at 1 p.m.

“Hundreds of downtown shoppers started in awe — at shoes, dresses, hats and ladies underwear in the shop windows,” Beacon Journal reporter Donn Gaynor quipped.

Calling themselves the Sun-Worshippers’ Club, a group of University of Akron students sacrificed a cockroach on Cascade Plaza to appease “the angry moon gods.” Illicit substances may or may not have been involved.

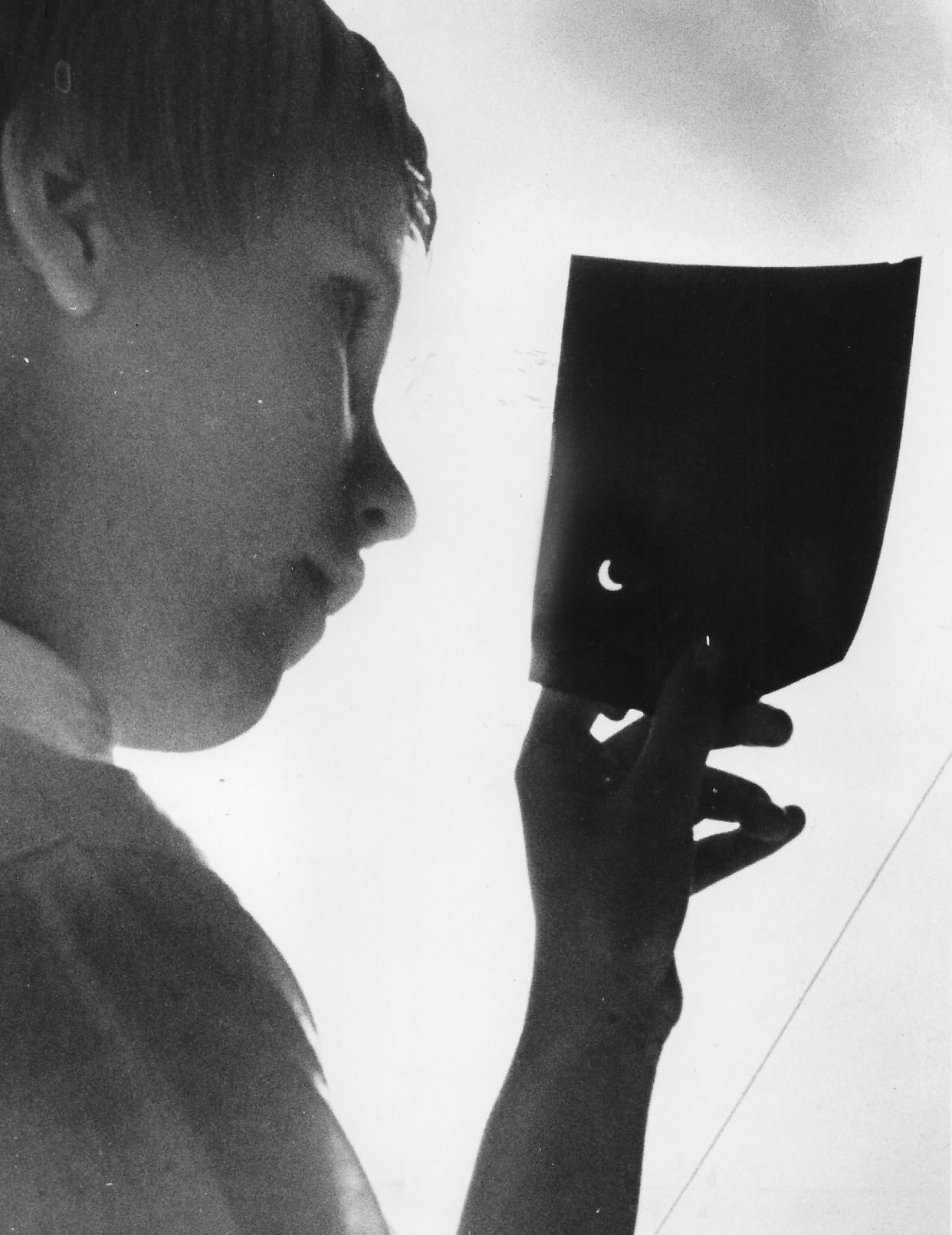

The Astronomy Club of Akron set up telescopes on Cascade Plaza to view the partial eclipse May 30, 1984, using a projection method. The safest way to watch an eclipse was to project the sun’s image on a white surface through a telescope, magnifying glass, binoculars or cardboard box.

Northeast Ohio residents hoped to see 80% coverage of the sun during the eclipse’s peak at 12:40 p.m. Millions of people enjoyed the “diamond necklace” effect that day in the Southeast. Unfortunately in Akron, it was — you guessed it — mostly cloudy.

1994 eclipse was impressive

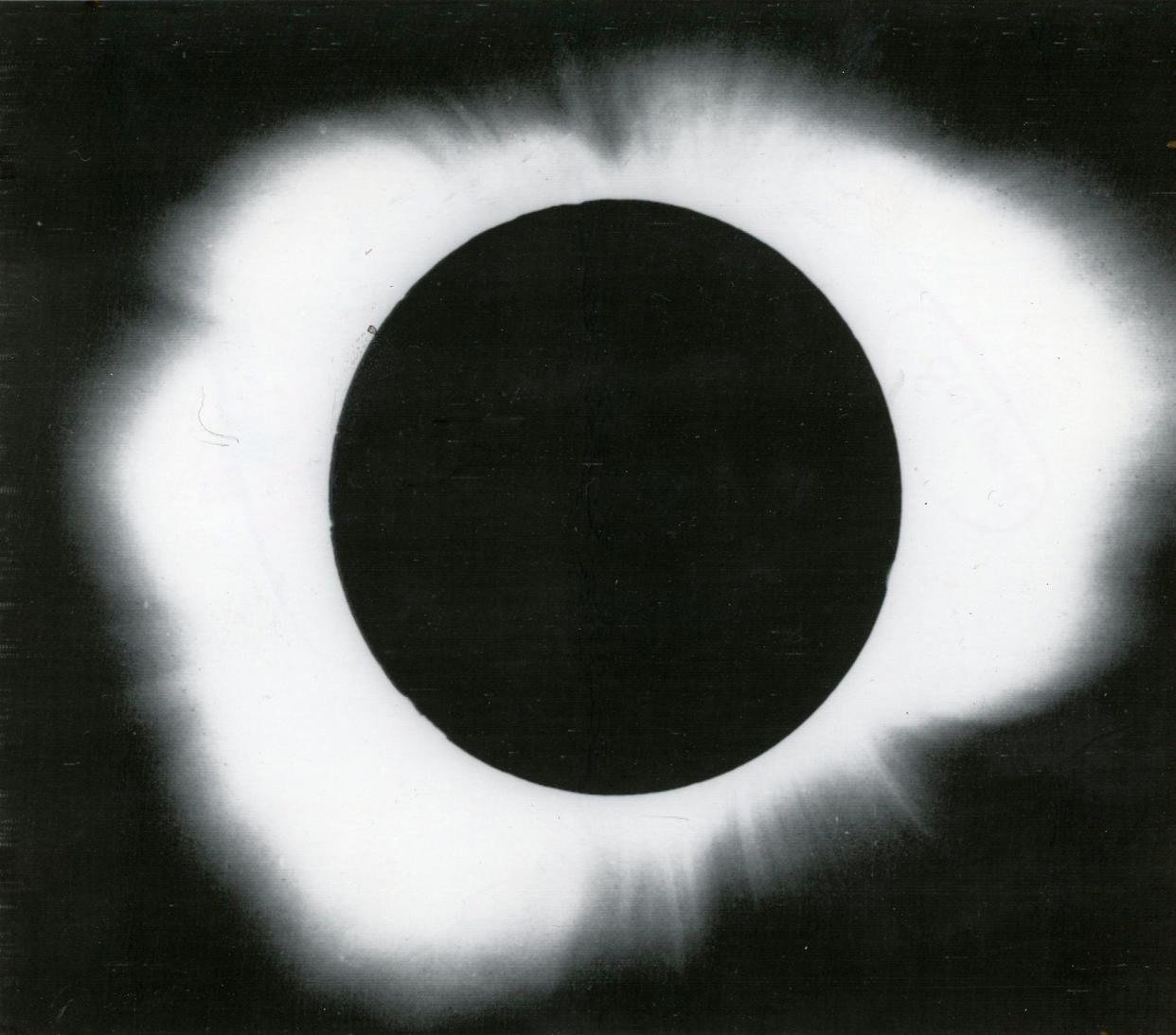

Finally in 1994, Ohio residents enjoyed the best show in decades. The annular eclipse on May 10 began at about 11:34 a.m. and ended at 3:04 p.m. A 150-mile-wide swatch ran southwest to northeast across North America.

Toledo, near the point of maximum eclipse, drew throngs of sky watchers. A thin ring of the sun surrounded the darkened shape of the moon. The ring appeared as a necklace of light for about five minutes.

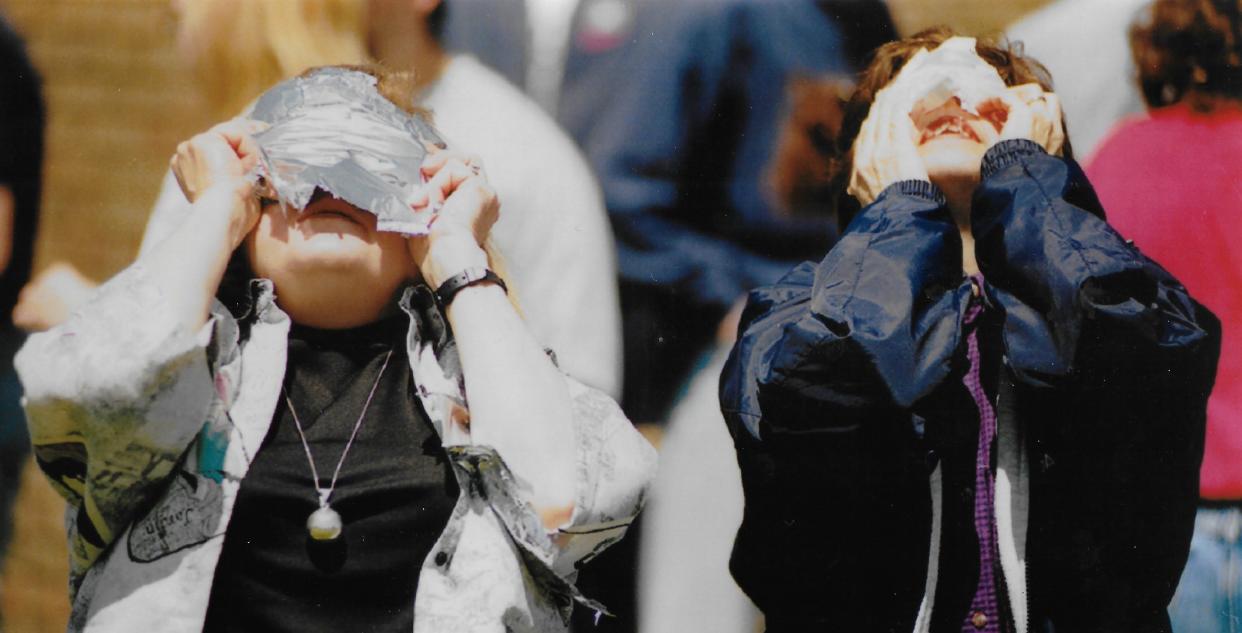

Across the state, people viewed the eclipse on screens through pinhole projections, through solar filters, welder’s glasses and two layers of exposed black-and-white film negatives.

More than 200 Kent State students took a break from final exam studies to attend an eclipse party at the campus planetarium.

“I don’t know whether I’ll ever get a chance to see another eclipse,” physics major Steve Arnold told a reporter. “I figured, even though I should be hitting the books, I owed it to myself to come out and take a look.”

Elementary schools were more cautious, keeping pupils inside, canceling recess and ordering children to stay away from windows.

“Suddenly, it seemed the earth invented a whole new set of colors,” Bill O’Connor wrote for the Beacon Journal. “The grass was a more profound shade of green and the dandelions deepened to a dark, orange yellow.”

An eerie quiet spread during totality. Then the moment was over. Ohio residents returned to their daily lives.

More recently, thousands of people converged on local parks to view a partial eclipse Aug. 21, 2017. Special glasses were must-have accessories as everyone gawked upward. The sun became a sliver with 80% coverage at 2:32 p.m.

Spectators oohed and aahed.

It was a warm-up act for this year’s headliner. Anticipation has been growing steadily for the total eclipse that will occur April 8.

May it be filled with wonder and beauty.

And nothing but clear skies.

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com

More: From ‘Black Hole Sun’ to ‘Moonshadow,’ an ultimate playlist of songs for the solar eclipse

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Solar eclipse story in Northeast Ohio begins with murder