Dan Auerbach Knows It When He Hears It

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Dan Auerbach pulls Tomorrow’s Gift, a hard-to-find pressing of the Krautrock band’s 1970 self-titled debut album, out from a row of records and examines the cover art. He studies the groovy, serif-heavy typeface and the interposition of the band members, posing in a park lawn on a crisp fall day in Deutschland.

“Notice the dinosaur logo?” Auerbach asks me, pointing to a barely perceptible tyrannosaurus rex insignia tucked away in the upper-right corner. At this, he chuckles.

It’s 10 a.m. in early December and Auerbach is the only customer at Record Safari, a vinyl store in Los Angeles’ Atwater Village neighborhood that specializes in rare finds and caters to the community’s abundance of DJs, producers, and everyday music nerds. (Just to give you a sense of how obscure Tomorrow’s Gift is, all of the band’s songs have less than 10,000 plays on Spotify.)

Auerbach doesn’t know what he’s looking for, but he’ll know when he hears it. “It’s intuitive,” Auerbach says of shopping for records. Discovering something special is like getting punched in the gut, he says. “I know instantly.”

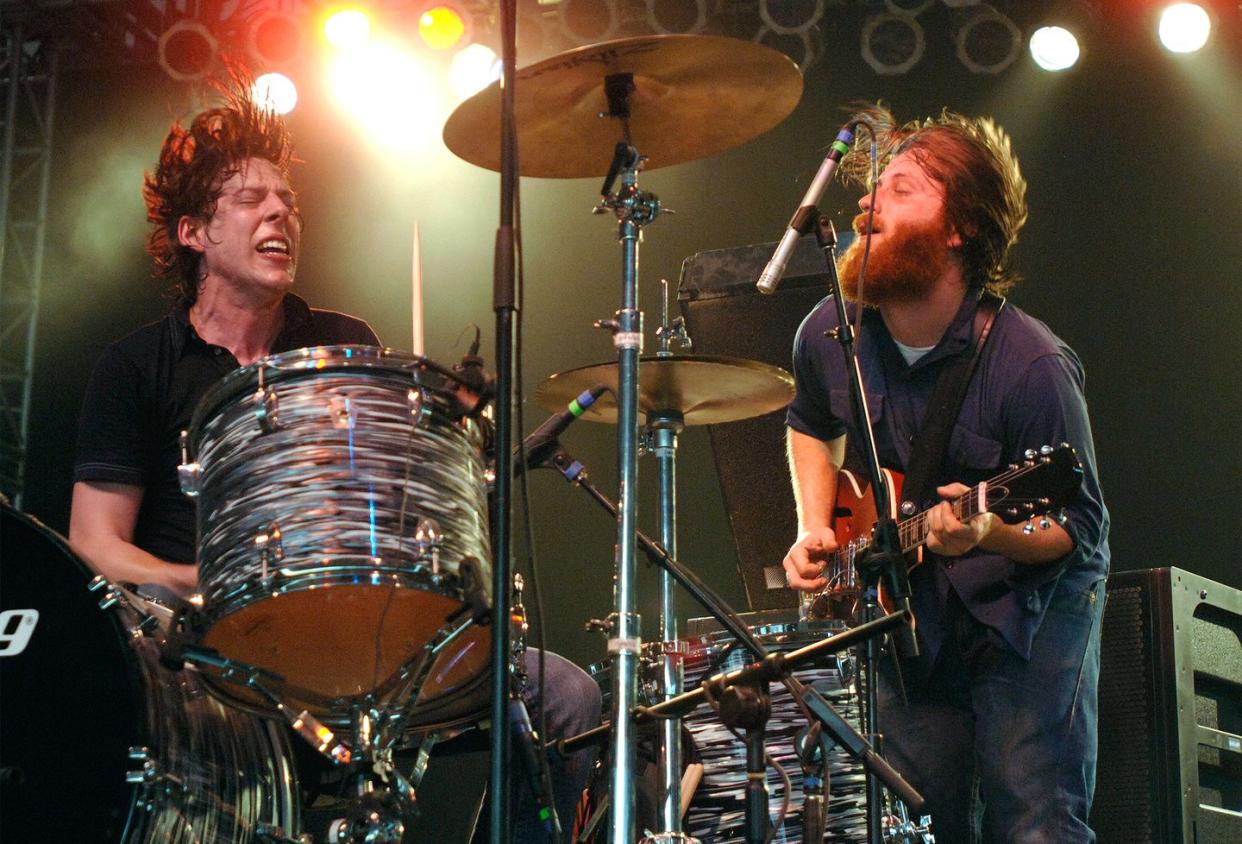

Twenty-two years ago in Akron, Ohio, Auerbach and Patrick Carney, then just high schoolers, began making music together, Auerbach on guitar and vocals, Carney on drums, in Carney’s parents’ basement. That teenage duo would go on to become The Black Keys, a lo-fi indie rock outfit that self-recorded their first four albums before experiencing an unlikely breakout and becoming, for a time, the biggest rock band in the world. Auerbach’s personal growth followed a similar trajectory, evolving from garage rock folk hero to one-man industry mogul. His second band, The Arcs, formed in 2015, releases Electronic Chronic, its second album and its first in 8 years, this Friday.

He’s one of the most sought-after producers in all of music, guiding the creative output of superstars (Lana Del Rey, Ceelo Green), indie darlings (Shannon & The Clams, The Velveteers) and country music royalty (Hank Williams Jr.) alike. His record label, Easy Eye Sound, now has 19 artists (including Auerbach himself, who releases his solo albums through the label), and it published eight albums in 2022, including a collection of unreleased recordings from one of Auerbach’s heroes, blues legend Son House.

Auerbach is the center of his own music industry ecosystem, composing, producing, publishing and performing music with a large and growing collection of creative partners, session musicians, employees and business partners. He has the creative bonafides to pursue any project he wants and enough capital to make it a reality, and the driving force of each pursuit is Auerbach’s well-honed, eclectic taste.

“No tattoos,” Auerbach says, handing me a Japanese album with a pin-up girl in a bikini, arms pristine, on the cover. Auerbach is correct—if that album were made today, the cover model would be inked up from neck to knuckle.

Record shopping is both business and pleasure for Auerbach, a chance to add to his prodigious personal collection and spark his own creative output. The Arcs, for instance, wrote their new album—a woozy mix of synth pop, celestial guitar riffs and plodding rhythm sections that feels like driving a Ford Bronco through the cosmos—by playing records for each other while on tour and finding inspiration in the arrangements.

“The Arcs, as a band, has always just been an excuse for a bunch of music nerds to hang out with each other,” bandmate Leon Michels later tells me. “We’re constantly listening to records and showing each other stuff. Finding a hook, drum fill, chord change, or just a vibe, and going from there to write the song.”

Back in L.A., Auerbach stalks the aisles of Record Safari, thumbing through stacks of LPs, inspecting them and, unmoved, returning them to their bins. His interest piques when the owner tells him about the store’s collection of rare 45s, though. “They’re like living, breathing artifacts,” Auerbach says as he methodically flips through the box brought out by the owner. “Imagine digging up a fossil and then you play it and people dance.”

When The Arcs were recording Electronic Chronic, they played Drake and Future songs for motivation. They loved Pusha T’s “Numbers on the Boards” and its combination of stilted, electronic percussion and soul sampling. But their favorite records were rare soul 45s from the ’60s and ’70s. Electronic Chronic features a cover of the 1967 Helene Smith record “A Woman Will Do Wrong,” a single so arcane that it’s not even streaming. (Many of the records Auerbach looks for have never been digitized, though you might be able to find a YouTube video of some music nerd spinning them on his turntable.)

![<p><a href="https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BHM9NTSK?tag=syn-yahoo-20&ascsubtag=%5Bartid%7C10054.a.42669993%5Bsrc%7Cyahoo-us" rel="nofollow noopener" target="_blank" data-ylk="slk:Shop Now;elm:context_link;itc:0;sec:content-canvas" class="link rapid-noclick-resp">Shop Now</a></p><p>Electrophonic Chronic[LP]</p><p>$22.99</p><p>amazon.com</p><span class="copyright">amazon.com</span>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/pHpSACflm9YMhD3tXlaXDg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcxOA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/aol_esquire_729/68b6ecc795feb7d68f612f635db8d744)

Electrophonic Chronic[LP]

$22.99

amazon.com

amazon.com“The influences are eclectic, because our tastes go all over the place,” Michel says. “There’s this slight competition, in a healthy way, when Dan and I record together. Everything was really fast. One of us would say, ‘I’ve got a part!’ and the other one is already coming up with an overdub.”

When Auerbach was a child, his dad, a home goods dealer, would take him antiquing. They would drive across the Midwest, visiting a network of collectors from Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, rummaging through their barns for goods and reselling the wares to housewives looking to furnish their living rooms with some antique sophistication or Americana kitsch. (If this father-son picking duo were operating today, they would almost certainly have their own TLC show.)

“Every time it was, ‘We’re going on a hunt. We don’t know what’s gonna happen. But at the very least we might have something good for lunch’,” Auerbach says, amused once again.

Auerbach recently saw a 45, “I Can’t Speak” by Jimmy Bo Horn, selling for $9,999.99 in a Detroit record store. “I was like, ‘This is a joke right?’ The clerk was like, ‘No, it’s 10 grand.” Though tempted, Auerbach didn’t buy it. “I couldn't do it,” he says. Even rock gods have their limits.

Almost all of the songs on Electronic Chronic were recorded years ago, while the group was on tour after their first album, so they feature drummer Richard Swift, who unexpectedly died in 2018 due to complications from alcoholism. Swift’s death was the catalyst for The Arcs finishing the recordings and releasing them as a new album.

“It was really strange at first, hearing him talk, hearing him laugh, hearing him count the songs in,” Auerbach says of revisiting the tracks. Recording the album helped Auerbach grieve Swift’s death. “But it was therapeutic, and something we had to do.”

Auerbach may be the creative leader of The Arcs, but Swift was the group’s emotional center, according to Michel. “No single person has influenced me as much as Swift in terms of my outlook on music,” Michel says. “When I met Swift, he was like, ‘Nothing matters. You can make a record however you want.’ He had an attitude of constant inspiration and output. Nothing could get in the way.” Swift would record songs in hotel rooms using rudimentary microphones purchased from Amazon. Sometimes Swift, a drummer, would count in songs saying, “A one, a two, I love, mu-sic.”

“When Swift left a room, the energy left with it,” Michel remembers.

Auerbach has a reputation for being a heavy dude, both musically and in person. The Black Keys became famous by producing a sonic sludge so powerful that it would have your puny home stereo throwing off sparks. That rough sound belied the fact that Auerbach, as both a musician and a producer, is an exacting taskmaster.

“For me, if a song is not working, I don’t care anymore. I’m good to move on,” says Michel, a prolific producer and label owner in his own right. “A couple times, Dan has worked through a song so obsessively, to the point where it wasn’t fun. But he broke through to the other side. I had given up, but Dan was bull-headed enough that he willed it to work.”

A good example is “Heaven Is A Place,” the first single off of Electronic Chronic, that features an unexpected mix of ethereal lyrics over a whomping guitar riff. Michel thought the song was “weird” and dissonant. “But Dan had a special feeling about it,” Michel says, and Auerbach kept rewriting it until it finally came together.

“Fuck yes I’m obsessive,” he tells me when asked. “In ways both good and bad.”

Auerbach takes a small stack of 45s to the store’s record player, listening to them through a pair of over-ear headphones. “You know Willy Mitchell?” he asks at one point, referencing the trumpeter and soul music impresario who produced Al Green’s best records. “Sonically, he just blew people away.”

In the end, Auerbach doesn’t buy anything. Apparently the store had a 50% off rare 45s sale for Black Friday and the place got ransacked. Auerbach piles into the back of the black Cadillac Escalade to check out Gold-Diggers Sound, a recording studio recommended to him by his friend Breezy, a local DJ and talent booker.

In the span of less than 15 minutes, he delivers mini-dissertations about the genius of everyone from the Grateful Dead (“Jerry Garcia had such a beautiful voice. So honest. Unpretentious. Frail,” Auerbach says) to “Rump Shaker” by Wreckx-N-Effect (“That was Pharell’s first hit,” Auerbach teaches me). Every word is delivered in a slow, soft-spoken, even cadence. He pauses after each question and stares into the distance before delivering each answer. One gets the impression that Auerbach spends almost all of his time deep in thought. Even the most dedicated of music nerds would struggle to keep up with the breadth and depth of Auerbach’s knowledge.

But Auerbach’s personal music preferences are more populist than one might assume, and he’s open to finding inspiration wherever it may come. His two solo records are downright poppy at times. In casual conversation, he has a well-honed, if wry, sense of humor. Driving to the record store, he offers me a hit of his joint, then tells me it has PCP in it, just like Denzel Washington in Training Day. Every third sentence he speaks is punctuated by a laugh. At one point, Auerbach guffaws looking at his phone. One of his employees texted him: “Doing arts and crafts late at night helps to stop the eternal screaming sound in my brain,” as good an explanation for creating art as any.

When The Black Keys debuted, they were an unlikely candidate to become the biggest band in the world. Playing a version of rock that harkened back four decades prior at a time when rock music in general was receding from the mainstream, their creations were raw and unsparing and actively defied prevailing cultural sensibilities. Auerbach had no formal production training. He was self-taught, all of his production choices were done by intuition. “We weren’t smart enough to come up with a master plan,” he says. “The hardest part was not thinking about it too much.” Auerbach had never even been in a professional recording studio until The Black Keys’ fifth album.

With time, though, the group crawled out of the basement and developed a sound polished and expansive enough to fill arenas. They began working with outside producers, most notably Danger Mouse (real name Brian Burton), famous for blending rock and hip-hop, and publicly mocked indie rock pretensions about the virtues of being niche.

“I just had to grow up and fucking realize that I didn't know everything,” Auerbach says of the group’s evolution. “We'd made four albums in our basement and it was like, ‘Let's go try something else. So what if it's got a bigger sound? Who cares? It's still gonna be us.’ Experiencing new things is always good, especially if you do it with someone you have a musical connection with.”

As a record label owner, Auerbach now has the opportunity to shepherd bands through that same learning curve. He points to Shannon & The Clams, a rockabilly outfit out of San Francisco, as one the label’s best successes thus far. “They’ve been crushing it, selling out shows, really making a living with their music,” Auerbach says.

Not everyone is as receptive. Years ago, he produced a record for the now defunct SoCal surf rock band The Growlers that the band ended up never releasing. “They were a little too scared. It didn't sound like it was recorded in a trash can,” Auerbach says, making himself laugh. “You can get caught in the lo-fi world and rely on it for your whole aesthetic.”

Earlier in our conversation, Auerbach told me that his father used the family home as a de facto storage unit and staging ground for his antiques. The house functioned something as a museum of Americana folk art, filled with vintage furniture and handmade quilts from the American heartland. Because his dad was a dealer, items would stay for a month before being sold off and replaced by something new. The home’s aesthetic was precisely curated and always evolving.

There's only one part of the music creation process Auerbach doesn't feel particularly well-suited for. As he says, “I don’t love the business aspect of it. To be truthful, the more I do it, the more it bums me out. That’s why I pay these guys, to have to deal with this shit all day,” Auerbach says, referencing the small cadre of employees he travels with.

The Escalade parks on Santa Monica Boulevard, just east of Hollywood, and Auerbach and co. explore the Gold-Diggers Sounds recording studios. Auerbach trades notes with one of the sound technicians about recording equipment; the owner of the space informs us that the studio was used by cult classic filmmaker Ed Wood. Wood’s 1959 production Plan 9 From Outer Space, widely regarded as the worst movie of all time, was filmed here. The trapdoor used to raise Bela Lugosi from beneath the floorboards has been left intact, a detail that delights Auerbach.

Breezy shows him Gold-Diggers Bar, the venue at the front of the complex, a small black box ideal for intimate live shows and sweaty dance parties. Auerbach looks over the controls in the DJ booth. “Put the DJ booth onstage,” he instructs Breezy.

Auerbach has added DJ to his lengthy list of job titles, dropping into rock clubs in between live gigs to spin records from his personal collection. Most of his record collection stays at home in Nashville, but he travels with a small collection of his most prized 45s—“For Goodness Sake” by Tommy Vann and the Professionals, “Hey Joyce” by Lou Courtney, Otis Redding’s “Shout Bamalama,” among others—to help him in pinch. He often brings his own speakers to ensure the sound is right.

“When I'm doing a DJ set, I'm kind of thinking about it like an album. I’m assembling all these songs and I have them arranged so that they steadily, gradually increase in tempo,” Auerbach says. “For someone who's always in the studio, getting to see how these records translate in person, with an audience, is really interesting.”

We’re still shy of lunchtime but inside the venue, Auerbach lights a joint, his second of the day. I joke that now Auerbach will want his own venue, and it elicits an earnest conversation between Auerbach and one of the employees about opening a Gold-Diggers in Nashville where Auerbach has lived since 2010. After the tour, Auerbach is whisked away again, this time to another recording studio where he’ll meet Carney to work on some new Black Keys songs.

There are worse things than having the skill and financial means to indulge your creative interests, but Auerbach’s responsibilities and schedule seem potentially overwhelming. Only to me, it turns out. “I like to be busy,” he says. “I get such a lift out of it everyday. When we do something good, the hair stands up on my arms. That’s what I’m searching for. Still.”

You Might Also Like