Dallas was the focus, but Fort Worth wasn’t to be left out of Texas’ centennial party

Amon G. Carter Sr., founder of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, viewed the 1936 Fort Worth Frontier Centennial celebration as one of the most important civic booster events the city had ever undertaken.

Although Dallas had won the state’s competition as the central centennial city in Texas’ celebration, Carter, William Monnig, and other civic leaders worked to showcase Fort Worth as a modern city, rooted in Western frontier culture and history.

Nearly a million visitors attended the centennial fairgrounds, located east of the Will Rogers Coliseum, in its four-month summer and fall run. Despite losing $75,000, Carter and Monnig, chair of the Fort Worth Centennial’s Board of Control, boasted the celebration a public relations success. Thanks primarily to New York showman Billy Rose, visitors enjoyed funhouse images of Fort Worth and the West, absent of significant African American, Mexican, Spanish, and Confederate histories.

Jacob W. Olmstead’s 2021 book “The Frontier Centennial: Fort Worth & The New West” recounted the formation of the festival’s glamorized western image. The Board of Control’s original plans sought to highlight Fort Worth’s frontier history, cattle industry, and diverse cultures of West Texas.

Local women’s clubs promoted infusing the celebration with authentic furniture, buildings, art, history, and books. They planned for Fort Worthians to dress in pioneer clothes as they greeted guests. Grasping Native American, Spanish, and Mexican influences in Texas’ development, the women expected displays of their historical and cultural contributions.

Eager to create a world-class attraction, Board of Control members employed Billy Rose, feted for his recent “Jumbo” circus Broadway show. They contracted Rose for $1,000 per day for 100 days, a high price tag for the time. Rose brought to town his razzmatazz showmanship to draw big crowds with entertainment, novelty, and sex appeal. He disdained historical pageants and museum displays as boring, and didn’t allow accuracy to hinder “Where the Fun Begins.” Instead, he exploited cowboy stereotypes as promoted in movies and novels, and the commercialization of women. A news ad boasted “Come To Fort Worth Frontier For Entertainment, Go Elsewhere For Education.”

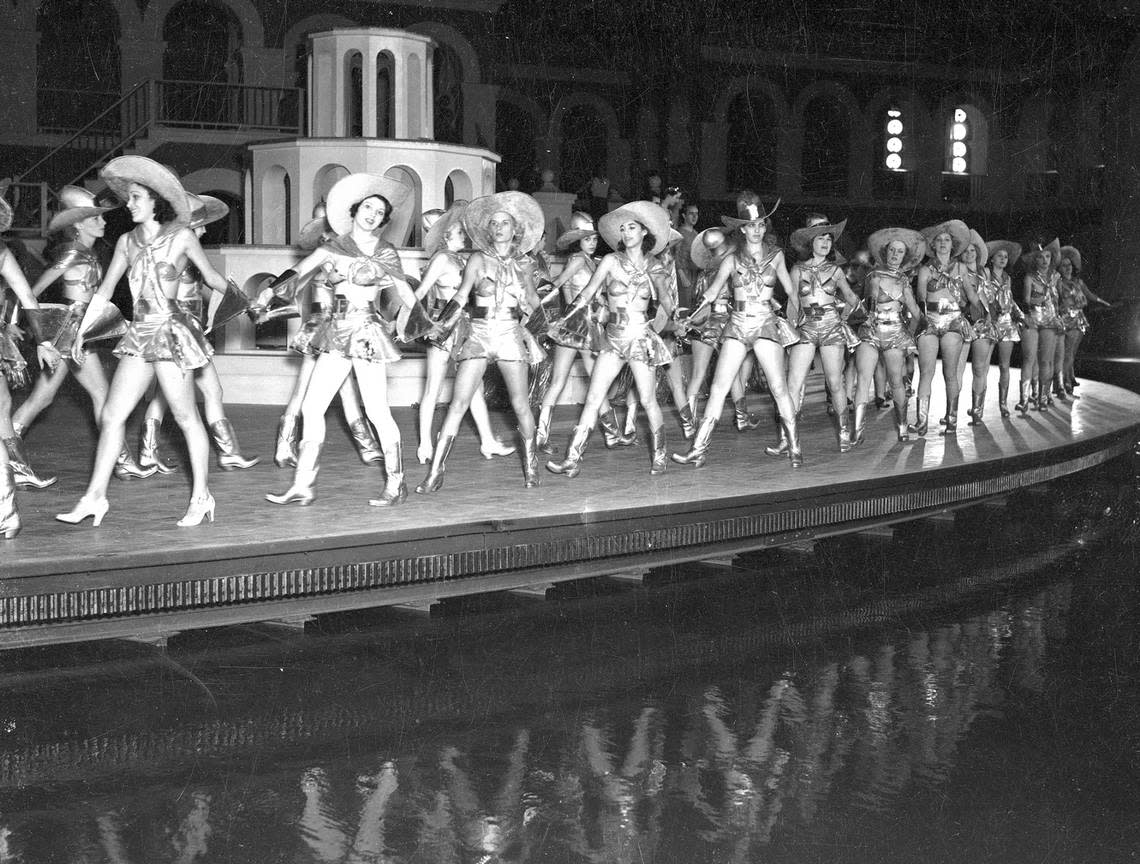

Rose re-staged his New York “Jumbo” show with 150 dancing girls, including at least one Latina. Centennial posters displayed females scantily clad in cowgirl attire next to a “Wild and Whoo-Pee!” invite. After local ministers and women leaders complained, Rose and Carter assured them the performances would be in good taste with no smut or nudity as performed in Rose’s New York shows. They exercised deft diplomacy when Rose hired Sally Rand, notorious for her feather and bubble dances, and Nude Ranch show, “Where the Wild West Goes Wild.” The Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Fort Worth Press poked fun at the sexual exotics with headlines “Recognize Her With Her Clothes On?” and “No Fair Peeping! 2 Youths Nabbed As Follies Cavort.”

Rose nixed the initial plans of a Mexican village with stucco archways, bell tower, tiled rooftops, shops, plaza, church, and a graveyard. Instead, the Mexican contribution consisted of an adobe where visitors could buy trinkets. Native Americans and bison performed in the “Last Frontier,” a rodeo/wild west show. Local African Americans responded to the exclusion of their admission, history, and culture by celebrating a “Century of Negro Progress” in that year’s Juneteenth festivities. As attendance for the “Jumbo” performances lagged, they were permitted to attend the show. Rose found another role for African Americans, hiring 200 as waiters for the Casa Mañana (House of Tomorrow) café/performance theater.

Showgirls starred in glittery-costumed dancing and singing performances on the Casa Mañana mechanically revolving stage, separated from the audience by a pool. The City Council in 1958 rebuilt the performance hall as a theater-in-the-round with a geodesic dome on the former fairgrounds and kept the name.

Rose envisioned a six flags theme park concept to memorialize the six nations that formed Texas. Although scant or no representation was displayed for some countries, his idea took root. In 1961, Six Flags Over Texas opened its first theme park in Arlington, now an international amusement park corporation. Disney World, Knott’s Berry Farm, and other amusements parks adopted the theme format.

In 1936, Amon Carter promoted the newly built Will Rogers Coliseum, Auditorium, and Pioneer Tower with its Art Deco and modern designs. Recreating Old Fort Worth with a weathered general store, saloon, dance hall, hotels, and hitching posts along Sunset Trail, Rose contrasted visually the city’s progress. Perhaps, by the 2036 bicentennial festival, Texas can boast true advancement into the new frontier of authentic African American, Latino, and female historical and cultural inclusion.

Author Richard J. Gonzales writes and speaks about Fort Worth, national and international Latino history.