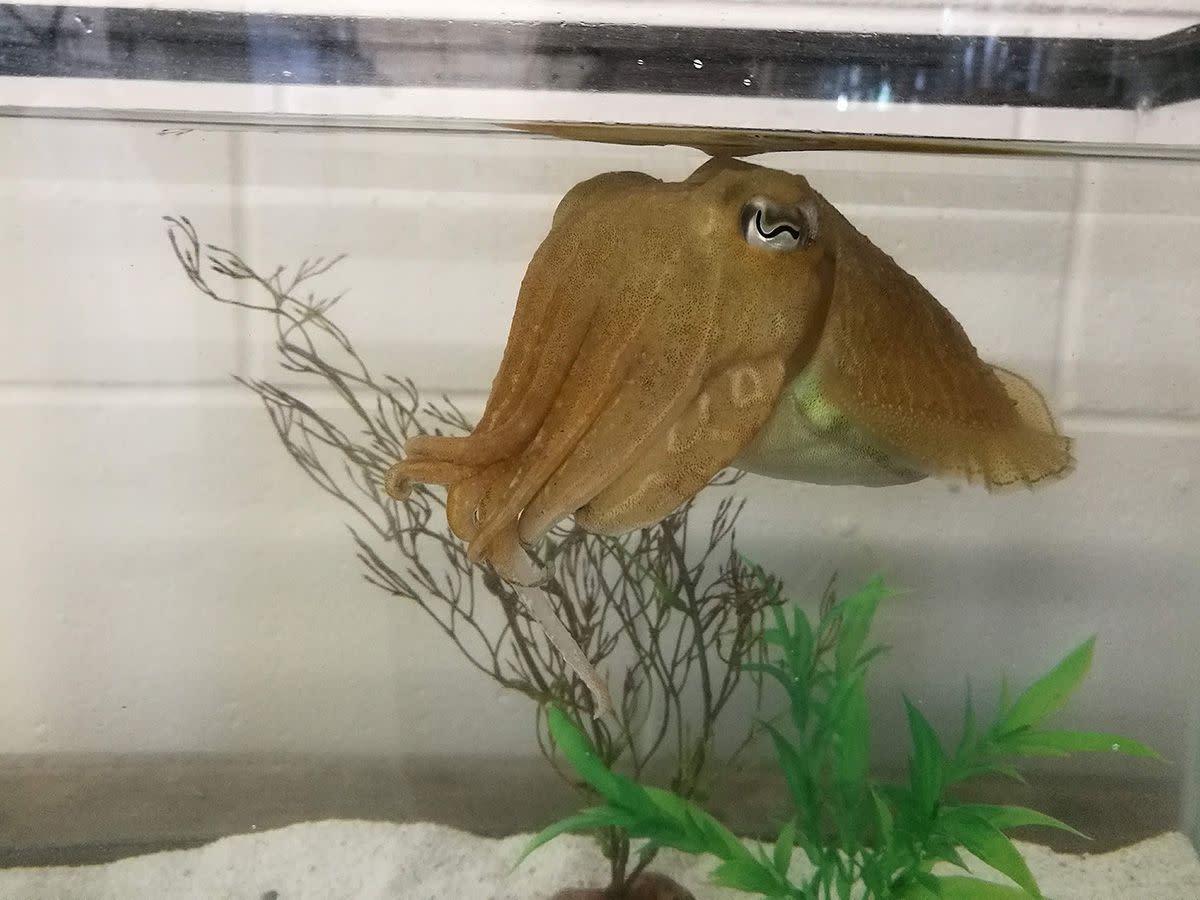

Cuttlefish pass ‘marshmallow’ delayed gratification test, indicating intelligence

The cephalopod cuttlefish has passed a famous psychological “marshmallow” test designed to gauge the propensity for delayed gratification in children.

The findings indicate that these sea creatures possess more intelligence than humans give them credit for, providing “the first evidence of a link between self-control and intelligence in a non-primate species,” according to a statement from Cambridge University in England.

Researchers created a modified version of the famous test given to kids in the 1960s, in which children were given the option of eating a marshmallow immediately, or delaying that gratification and receiving two.

To assess the cuttlefish’s ability to delay gratification, scientists plied the animals with a piece of King Prawn in one chamber that they could eat immediately. In another was a live grass shrimp, which they like better, but could only have if they held off eating the prawn, the researchers said.

The research was conducted at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., while lead author Alexandra Schnell of the University of Cambridge in England was in residence there, according to a release. Cephalopod leading behavior expert Roger Hanlon also collaborated. The research was published this week in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Delays ranged from 10 seconds all the way up to 130 seconds, and all six cuttlefish in the experiment showed at least some degree of self-control, ignoring the king prawn as they waited for the grass shrimp, the release said. The 130-second delay was on par with large-brained animals such as chimpanzees, the researchers said.

The better the learning performance, the better the self-control, the researchers found. Just as interesting, as they practiced self-control, the cuttlefish actually turned away from the immediately available food and distracted themselves from the temptation, the researchers noted.

“It was quite astonishing that the cuttlefish could wait for over two minutes for a better snack,” the paper’s main author, Alexandra Schnell in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Psychology, in a statement. “Why would a fast-growing animal with an average lifespan of less than two years be a picky eater?”

Why indeed? The self-control mechanism could stem from the amount of time these cephalopods lie still on the seabed to avoid predators, researchers surmised. This discernment could be a function of their need to conserve energy for quick foraging forays.

“Cuttlefish spend most of their time camouflaging, sitting and waiting, punctuated by brief periods of foraging,” Schnell said in a statement from the Marine Biological Laboratory at the University of Chicago. “They break camouflage when they forage, so they are exposed to every predator in the ocean that wants to eat them. We speculate that delayed gratification may have evolved as a byproduct of this, so the cuttlefish can optimize foraging by waiting to choose better quality food.”

Regardless of what underlies the cuttlefish’s ability, it shows they understand complexities.

“The ability to exert self-control is an important element of the ability to plan for the future, which is quite a sophisticated behavior,” said Professor Nicola Clayton FRS in Cambridge’s Department of Psychology, senior author of the report. “Self-control requires an understanding that ‘less is sometimes more’ — that avoiding temptation now might lead to a better future outcome. This is a critically important building block for the evolution of complex decision-making.”