Crist and DeSantis, both instinctive politicians, bring rival management styles

Florida voters have a choice this election cycle between two leading candidates for governor who have both served four years on the job, faced the headwinds of environmental or economic crises, and whose ambition for higher office was a hallmark of much of their tenure.

Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and Democrat Charlie Crist — a former Republican governor himself — have been tried and tested by a hurricane, a pandemic, a deadly building collapse, a windstorm insurance meltdown, out-of-control property taxes and an oil spill. They approached the crises with opposite management styles, shaped by their their instinctive approach to politics and very different personalities.

Crist was elected in 2006 as Florida’s 44th governor after four years running the attorney general’s office and six years in the state Senate. A Republican who left the party in 2010 and served just shy of three terms in Congress as a Democrat, he spent much of his time as governor finding consensus on thorny legislative issues as his party moved to the right.

DeSantis also had a taste of what it meant to work with a Legislature when he was sworn in as governor, having spent six years in Congress. He came to office after defeating Andrew Gillum, then the Black mayor of Florida’s capital city, by fewer than 34,000 votes.

As the youngest governor since Park Trammell was elected in 1913, and with no previous executive experience, DeSants also had to become a quick study.

An inside look at their first terms as governor suggests that, despite some striking similarities, they would bring drastically different approaches to the job.

DeSantis’ campaign did not make the governor available for an interview and refused to respond to requests for comment.

In an interview, Crist said his management style is not complicated.

“I have always believed that you try to surround yourself with the best and the brightest, whether they’re agency heads or whatever they may be, and give them the opportunity to lead,’’ he said. “Try not to interfere too much.”

‘Cheerleader’ v. ‘Commander’

In interviews with more than a dozen current and former staff of both governors, a picture emerges of two men who are both instinctive and ambitious politicians, often shunning conventional wisdom to rely on their own judgment, a trait that allowed each of them to push the envelope on politically-charged issues and achieve popular success during their time in office.

“Gov. Crist was a ‘cheerleader in chief,’” said Jeff Kottkamp, who served as Crist’s lieutenant governor and is now a lobbyist. “He would set broad policy and leave the details to those he put in charge of the issue.”

By contrast, Kottkamp said DeSantis operates more like a “commander in chief, which isn’t surprising given his military background,’’ a reference to DeSantis’ three-year stint in the Navy’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps. “He also is far more involved in getting involved in the details.”

Both men have defied conventional wisdom and expected their agencies and staff to follow.

Crist made orthodox Republicans squirm when, during the first half of his term, he put a focus on climate change and the need for renewable energy and pushed for automatic restoration of rights for some convicted felons.

He argued it “was the right thing to do,” but when the worst economic recession since the Great Depression hit in 2008, Crist stopped advocating for changes in energy policy and he shifted his focus to pocketbook issues.

DeSantis’ narrow victory meant he needed to broaden his base to strengthen his hold on his office. In his inauguration speech, DeSantis vowed to help “overcome tribalism that has dominated our politics.”

He pushed for increases in new teachers’ pay and he and the Cabinet met as the clemency board to pardon the Groveland Four, the four black men wrongly accused of sexually assaulting a white woman in 1949.

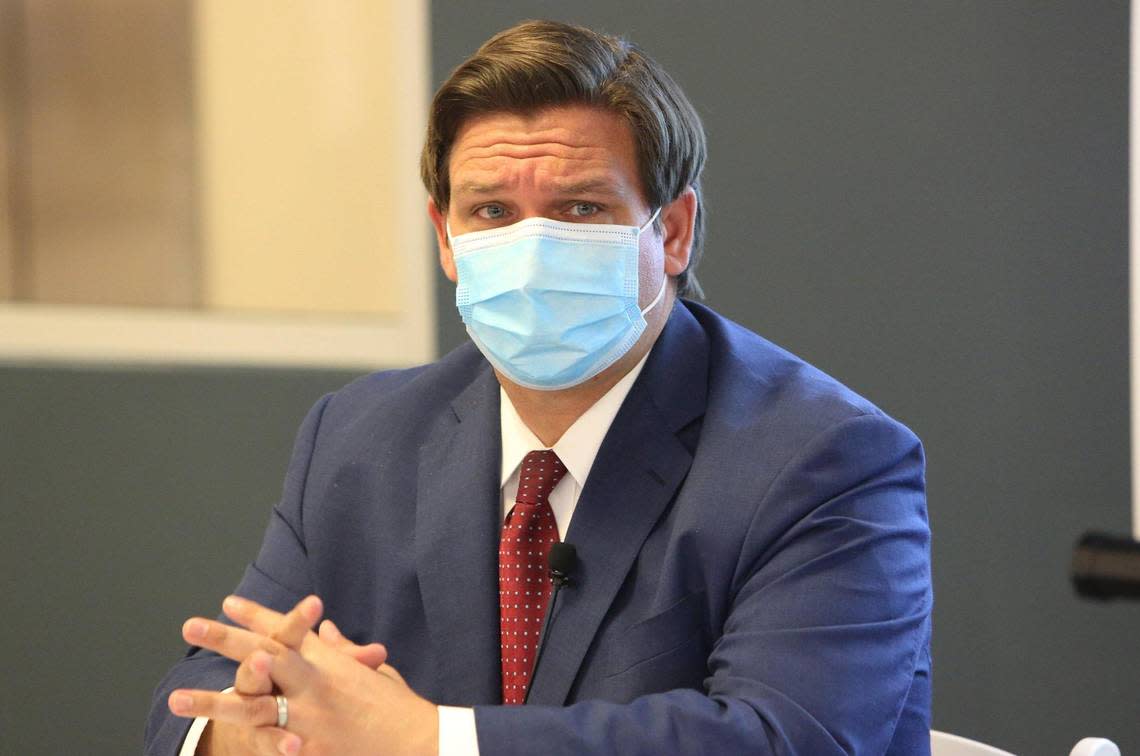

But his centrist approach changed when he faced his first crisis, as the pandemic hit in March of 2020 and threatened to devastate Florida’s tourism-dependent economy.

DeSantis’ first impulse was to follow the advice of public health experts, ordering widespread shutdowns in March through April. The decision, which he has since suggested he regrets, sent shock waves through the economy, with many businesses lamenting the closures.

DeSantis tackled the political fallout by taking a cue from the Trump administration and used temporary declining caseloads as his rationale for scaling back restrictions in May 2020.

As he came under fire for withholding COVID-19 data and for criticizing lockdowns, DeSantis decided he would open the state full-throttle. He prohibited local officials from implementing their own restrictions, accepted community spread of the virus while protecting the elderly and, while he initially brought the scarce supply of vaccines first to Republican-friendly communities and the elderly, he then leaned into vaccine skepticism.

“Once he decided where he wanted to go, there was no turning back,’’ said a former DeSantis top official. “He just says, I don’t care what the situation is, I’m going to apply this core set of values and beliefs to the situation. And I’m going to come out on top.”

All current and former members of the DeSantis administration who spoke to the Herald/Times for this article did so on the condition of anonymity because of the pushback insiders say they receive for speaking on the record.

DeSantis’ governing approach was foreshadowed by former Gov. Jeb Bush, who told an audience at a Wall Street Journal event after the 2018 election that he had asked DeSantis how he was going to win. “’He goes, ‘I’m going to nationalize the primary and localize the general,’’’ Bush recalled.

The strategy not only worked to bring DeSantis electoral success, but it would eventually prove to be his strategy as he embraced an agenda of culture wars that has allowed him to appeal to a national conservative audience.

“He has a skill for identifying things that agitate everyday people,’’, said Susan MacManus, a University of South Florida political analyst. “He marries national issues with Florida and does it better than any governor around.”

For example, when DeSantis learned that Hillsborough County State Attorney Andrew Warren may have received financing from left-wing financier George Soros and vowed not to pursue criminal cases involving abortion or transgender care, the governor suspended him, risking the chance his decision could be overruled in court, she said.

By targeting Warren, DeSantis helped to elevate the anger people were having about “criminals being led out on the street and recommitting crimes,’’ MacManus said.

Crist’s crises

Because of the economic conditions and crises facing Florida during the late 2000s, Crist, by contrast, was forced to keep his focus on state issues. In the process, supporters said, he demonstrated instincts that demonstrated an ability to discern what mattered to average Floridians, even though it often contradicted what leaders of his party wanted.

In Crist’s first year, he entered into negotiations with the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ending years of delay under Bush, and signed a landmark deal to usher in casino gambling in Florida. The gambling deal provided the state with needed revenue in the recession.

Like DeSantis’ mandates over local government and school districts in response to the pandemic, Crist used the power of the executive when he was unhappy with the direction of a policy.

After evidence emerged that members of the Public Service Commission, the state board that regulates utilities, had become too close to the utilities, Crist replaced two commissioners whose terms had expired with people who had no ties to the industry whom he expected to better balance consumer interests.

When policyholders of Citizens Property Insurance were facing a 56% increase in windstorm rates when Crist came into office, he worked with then-Sen. Steve Geller, a Democrat, to reach a compromise with Republican leaders that would lower rates by 25% for private insurers and reduce rates for Citizens policyholders by at least 20%.

When homeowners were stung by rising housing prices, Crist supported a bi-partisan state Senate plan to pass a 2008 constitutional amendment to expand property tax exemptions for homeowners.

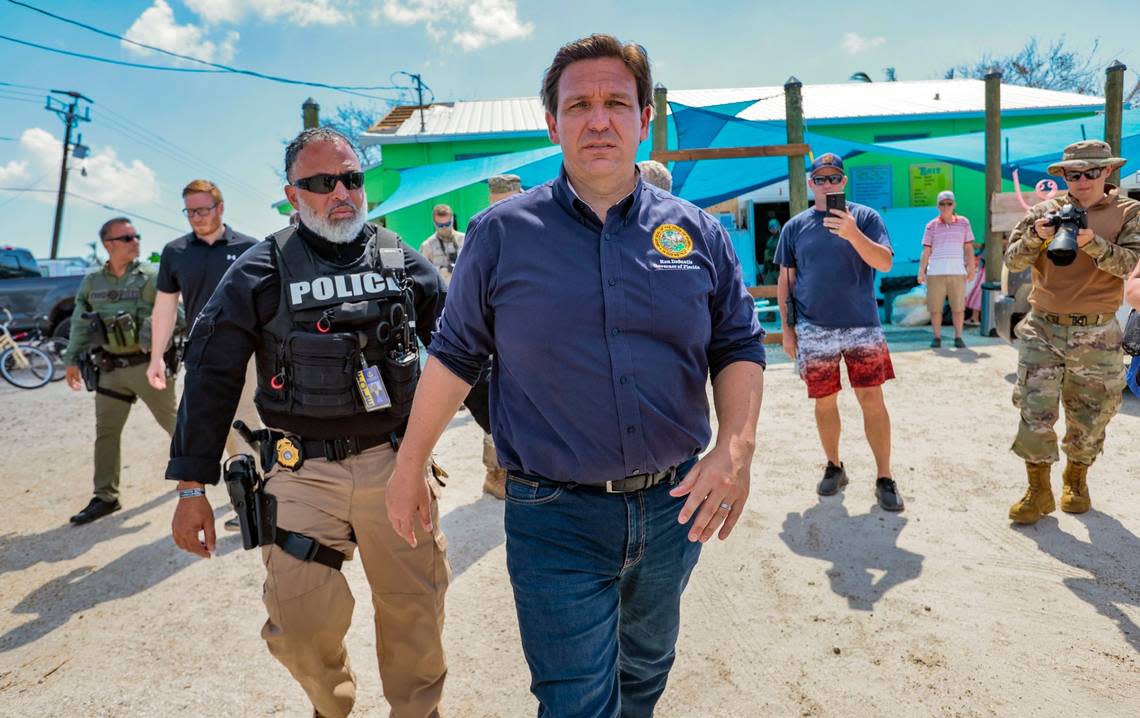

And when BP’s oil well exploded in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010, Crist responded by relocating his team to the Panhandle coast, with news cameras following him everywhere.

Having announced he was running as an independent for U.S. Senate, he also made the most of the political opportunity. He reversed his previous openness to offshore oil drilling, and convened a special legislative session demanding that Republican lawmakers put a proposed constitutional amendment on the November ballot to ban drilling.

But as a sign of Crist’s declining clout, within hours, legislators gaveled in and gaveled out, rejecting it.

Today, Crist credits then-President Barack Obama for helping Florida by delivering $12 billion in stimulus money to help the state recover from the Great Recession, and for working to hold BP accountable to pay for its damages and return millions of dollars to Florida’s affected communities.

“I think by and large, it was appreciated by Floridians as a whole, because it was a difficult time, and we needed help,’’ Crist said Friday.

Different approach to agencies

To achieve his goals of keeping the agenda nationalized, much of DeSantis’ operation is run “out of the plaza level,’’ three current and former officials said, referring to the governor’s suite on the first floor of the state Capitol.

“We would prepare talking points beforehand and everything was approved by the staff ahead of time,’’ said one former agency head.

The governor’s executive staff convenes in the Capitol suite every morning, to review what the day will look like. Fox News is on in the background everywhere. And, as a measure of how skittish the administration is about public disclosure, “even his top staff is often not told where the governor was going,’’ one former aide said.

His former aides described meetings with DeSantis as often like his news conferences — lengthy monologues from the governor with little room for input or inquiry from staff.

“The secretaries might stand with him at a press conference but they’re not having the level of engagement as in the past. With Crist, there were more briefings,” said one Tallahassee veteran who is close to the administration and worked for two former governors.

Public records released by the governor’s office show the extent to which the enterprise is focused on national media attention. The staff compiles daily reports on each of the governor’s culture-war initiatives, listing media mentions with a focus on “national media push,” “amplification within the press,” and “amplification within groups.”

In a document listing the “earned media coverage highlights” of the “Parents bill of rights,” which is called the “Don’t say gay bill” by opponents, the citations are listed in order. The first top 11 media groups are conservative and right-wing news organizations. The following seven are legacy news organizations. None of the news sites tracked are local.

DeSantis collects information by reading and absorbing data, his aides said. His routine includes rising before dawn to read a thick, printed binder of briefing materials, prepared by staff daily and delivered to the Governor’s Mansion every morning. Aides say that when he is not traveling, he is out of the office by 5:30 p.m., spends time with family and returns to his office in the Mansion by about 8 p.m.

“He isn’t the kind of politician that says, let’s sit in the room and you guys give me your thoughts on this issue and then I’ll make a decision,’’ said one former top aide. “He’s not one for meetings and he doesn’t like chit-chat.”

“It was always: the decision has been made. Now execute it,’’ the ex-aide continued. “It made some people feel very safe in their job because they knew if they got done what the governor wanted them to get done, they would be fine. But for those who wanted to kind of expand their role or change the course of their agency, it was frustrating.”

With a top-down management style employed by the chief executive, the cogs of government are linked at the chief-of-staff level. That position is held by the governor’s affable Chief of Staff James Uthmeier, a former Trump Commerce Department counsel and an alumnus of Jones Day, the powerful national law firm with deep ties to the Republican Party.

Uthmeier, a lawyer first hired by the governor to serve as his general counsel, brings a more collaborative, “less control-oriented” approach to managing the office compared to the governor’s first chiefs of staff, Shane Strum and Adrian Lukis, said one official, who has worked for several governors.

Crist said in an interview that he collected information through “regular meetings with all the secretaries in the governor’s office” in which he would “give them an opportunity to voice their concerns, what they were working on and just have a free open, transparent discussion.”

He said he also visited the agencies to “walk the ship” and get feedback on the operation.

Crist’s former staffers say he also is no fan of meetings. In a sweeping profile of Crist in 2014, the Tampa Bay Times reported that the aides its reporters talked to said that “the governor did not appreciate second-guessing or encourage free-flowing, two-way policy talk.”

By contrast, supporters say Crist set the agenda, but let his agencies run unfettered.

“He surrounded himself with very bright people who were able to effectuate the things he wanted,’’ said Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber, who served as House Democratic Leader when Crist was governor. “He didn’t have a war room against the Democrats, or against anyone, he had real pros who understood the policies and their missions. He gave them guide rails and then relied on them.”

Although Crist did not attend many agency head meetings, his chiefs of staff set expectations and demanded results, but did not micromanage.

Kottkamp said he was given broad authority over the Office of Drug Control, the Office of Adoption and Child Protection, and the Office of Film and Entertainment.

“The day-to-day activities of those offices went through my office — not the governor’s office,’’ he said.

Crist “wasn’t into the details, but there was trust in the agencies and in his leadership team to execute,’’ said one former staffer.

“He didn’t interfere,” former Secretary of State Kurt Browning told the Tampa Bay Times at the end of Crist’s term in 2010. “He turned me loose and, I hope, trusted me enough to do my job.”

Aloof or too loyal?

Former staffers of both governors described differing approaches to how their boss perceived loyalty.

Crist was accused of often waiting too long to discipline subordinates or those who abused privileges. He remained loyal to former Republican Party Chairman Jim Greer until he was convicted of pocketing $125,000 in party donor money.

And on Friday, news broke that Crist’s 2022 campaign manager had been arrested, along with his domestic partner, in a domestic violence case a day before he resigned from the campaign. Neither Crist nor the campaign had mentioned the arrest when Austin John Durrer’s resignation was announced on Wednesday. The campaign said Friday Durrer was removed as soon as they learned of the arrest.

For DeSantis, the roster of former aides is lengthy. Only one member of his staff, senior advisor Drew Meiner, has remained with him since his time in Congress. Many said the governor’s aloofness contributes to turnover in his office ranks.

“With DeSantis, it’s like everybody loves what he does. But they don’t love him,” one former aide said.

Politico reported that aides would lure DeSantis to staff meetings with cupcakes, saying that it was a colleague’s birthday to get him to attend.

When it comes to political and governing advice, both DeSantis and Crist rely on a very small circle of advisors but turn first to a family member for their most reliable counsel.

Casey Black DeSantis, the governor’s 42-year-old wife and former television broadcaster, is his most trusted advisor, who keeps an office near his in the executive suite.

Crist’s closest advisor has always been his father, Dr. Charles J. Crist, the son of an immigrant from Cyprus whom the governor would speak to daily during his term.

One of the hallmarks of Crist’s tenure was his use of the Governor’s Mansion, which he referred to as “the people’s house.” He would to gather legislators, donors, supporters and those he was trying to lure in support.

The dinners would be listed on the governor’s daily schedule, released via e-mail early in the day, and if the attendees involved elected officials – technically making the gathering subject to the state’s open meeting laws – reporters would be allowed in to record the meeting.

DeSantis’ style is not one wed to formalities. He is widely regarded as awkward in one-on-one encounters and uses the Mansion selectively, such as for holiday parties but rarely to entertain. A dinner in January included Dave Rubin, the popular right-wing web talk-show host, and Benny Johnson, a Newsmax host.

Deep differences over media

One of the biggest differences in terms of governing styles is how Crist and DeSantis approach the media and transparency.

Crist created the state’s first Office of Open Government to guard against secrecy.

DeSantis ordered staff not to release his daily schedule in advance, withholds details from what is releasead, and urges staff not to write down any sensitive information to avoid creating a record. Public records requests for staff members calendars are often empty. Text communications between top aides is reported to be non-existent, and phone logs are not released.

Despite Florida’s robust public records law, DeSantis’ agencies and the governor’s executive staff have worked to withhold unfavorable COVID-19 data and details on the governor’s controversial migrant flights to Martha’s Vineyard as long as possible. Only after the Miami Herald, Tampa Bay Times and other news organizations threatened a lawsuit were details released on the number of COVID-19 cases in hospitals, nursing homes and schools, and the contract details on the migrant flights.

Crist routinely would return reporters’ phone calls, and he allowed his agency and executive staff to speak to the press.

According to public records released by the governor’s office, DeSantis has assembled one of the largest communications staffs in state history. The governor, however, has intentionally walled himself off from most independent media organizations.

Early in his term, DeSantis’ press conferences began as awkward events. A bank of cameras would line-up in front of him with reporters behind them, but as reporters asked questions, the governor would keep his eyes fixed on an imaginary spot on the floor, to appear as if he was speaking to the cameras.

In his first several months in office, DeSantis would surround himself with legislators at his news conferences and never introduce them. After supporters started to mention it, he began to include the introductions. They are always without fanfare — usually a quick read of a name from a list, proceeded with the words: “Okay, next.”

At his wife’s encouragement, he began to conduct more news conferences, using the state plane to fly to different cities and talk about his policies, benefiting from the publicity during a campaign cycle. He became more comfortable talking to crowds and reporters.

Since the summer of 2020, however, DeSantis has mostly given interviews to conservative publications that amplify his message and refrain from rigorous questions.

“He got really insular and really pissed off by the coverage he was getting, because he felt it was unfair,’’ a former aide recalled. “I think it just poisoned the well.”

The conflict with reporters has now become part of his national appeal to the conservative base. In a recent campaign ad, DeSantis wore sunglasses and a bomber jacket to portray himself as Maverick from ‘‘Top Gun’‘ while boasting about ‘‘dogfighting’‘ the ‘‘corporate media.’‘

When Politico confronted DeSantis’ communications staff with a list of questions last year based on interviews with disgruntled DeSantis staffers, then-Chief of Staff Adrian Lukis went on the defensive. He complied a report of his own and sent it to Politico: a five-page document of favorable DeSantis quotes from current and former staff members who otherwise had been told not to talk to the media.

Despite their dramatically different approach to managing government, and to getting public attention, both DeSantis and Crist enjoyed above-average approval ratings during their terms.

For Crist, whose term was marred by foreclosures and bank failures as the national economy struggled, his approval ratings remained in the 60% and 70% range. And DeSantis, who serves during a more polarizing political era, has managed to keep his approval rating close to 50%.

Mary Ellen Klas can be reached at meklas@miamiherald.com