COVID in Boise wastewater is highest it’s been in 2 years. This is what to know.

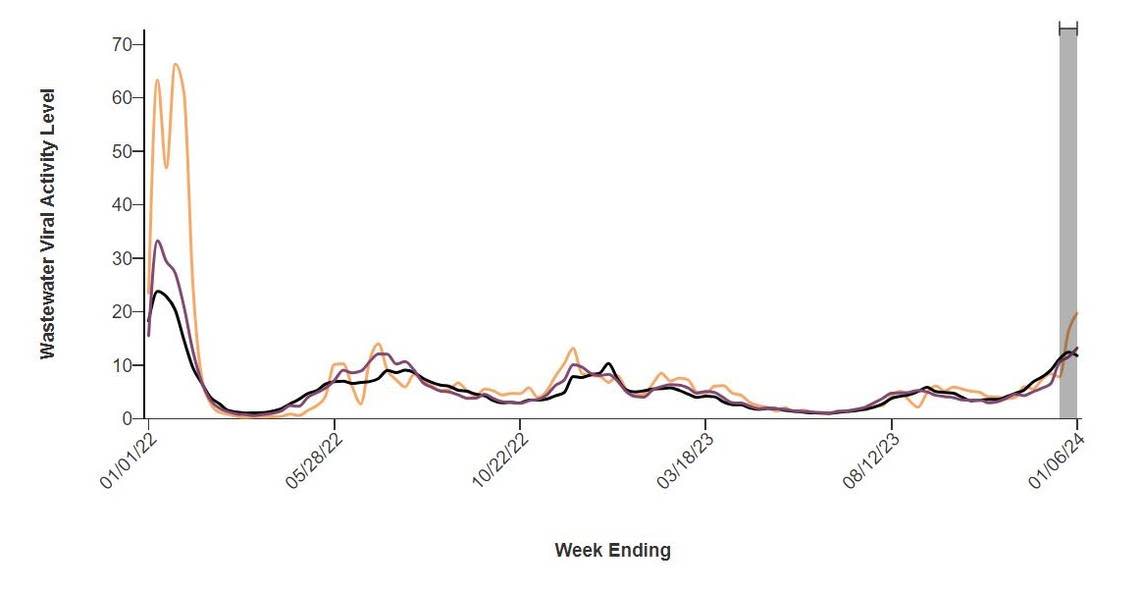

Wastewater analysis sites in Idaho are reporting the highest levels of COVID-19 in nearly two years.

Levels of the virus in the state’s wastewater samples are the highest they’ve been since February 2022, during the first wave of the Omicron variant, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The CDC says wastewater monitoring can detect the virus’s spread from person to person within a community earlier than clinical testing and before sick people go to their doctor or the hospital.

Increased levels indicate a higher risk of infection.

The CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System now categorizes Idaho as having “very high” viral activity — the highest level defined by the agency.

In Boise, wastewater data follows the statewide, and nationwide, trend.

A new variant named JN.1, first detected in the U.S. in December, is the fastest-growing variant in the country, the Idaho Statesman previously reported. By Dec. 18, the most recent date for which data is available, JN.1 accounted for 55% of all circulating COVID-19 variants in Boise, according to the city’s wastewater dashboard.

‘We have never seen a jump that fast’

Dr. David Pate, former CEO of Boise-based St. Luke’s Health System, said wastewater sequencing, which is more costly to do than simply testing for the virus, allows communities to see which variants are most dominant.

For the seven-day period ending Nov. 27, there was no evidence of JN.1 in Boise wastewater. But by Dec. 4, the variant made up 77% of all variants.

“We have never seen a jump that fast,” Pate told the Statesman by phone. “It shows the growth rate is so high that it displaced all other variants. Today, it’s becoming the predominant (COVID-19) variant across the entire world, not just in Idaho and the nation.”

The city of Boise treats wastewater for Boise, Garden City and Eagle at its two sewage treatment plants, on Lander Street and West Joplin Road. Samples are sent to the Hampikian Lab at Boise State University to be tested for the virus.

Wastewater analysis is one of the best methods of tracking the spread, Pate said, as fewer people test and even fewer report those results to local or state health officials.

The other ways to track transmission are less current, but include hospitalizations, which lag behind wastewater results, and deaths, which lag behind hospitalizations. Typically, people infected with COVID-19 don’t become hospitalized until the second week of illness, he said.

“We can detect an outbreak in wastewater before it actually occurs,” Pate said. “We can use it to make estimates about how many people might become infected.”

Unlike flu, COVID-19 is not seasonal

He added that, while some have likened COVID-19 to other illnesses like influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which have distinct seasons, the evidence is clear that COVID-19 is not a seasonal virus. While state, national and global metrics now show a spike, he said the virus has been able to sustain relatively constant transmission year-round for nearly four years, which is “unprecedented.”

Pate acknowledged that many people don’t care to avoid an infection. But for people who want to be mindful of their risk, wastewater levels are the best way to inform week-to-week decisions about what precautions to take.

“I spoke with someone just the other day who has a family member who is immune deficient, and that person is very careful, because they don’t want to infect the person they care about,” he said. “I also talked to a guy with a liver transplant and a mother who was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer, and they were scared for the same reason.”

The amount of viral load found in local wastewater will likely continue to rise for at least a couple of weeks as students go back to school after the winter break, he said.

The latest data shows about 75% of infections that occur in families stem from a child who brought it home from the classroom or day care, he added.

“It’s really hard to predict these things, but I do expect a further increase in cases,” Pate said. “This is the second-highest surge we’ve had since the beginning of the pandemic.”

Is the new COVID-19 variant JN.1 ‘more transmissible’? What to know about COVID in Idaho

Washington restricts license of controversial Idaho doctor for COVID-19 ‘dishonesty’