COVID-19 U.S. death toll reaches 1 million

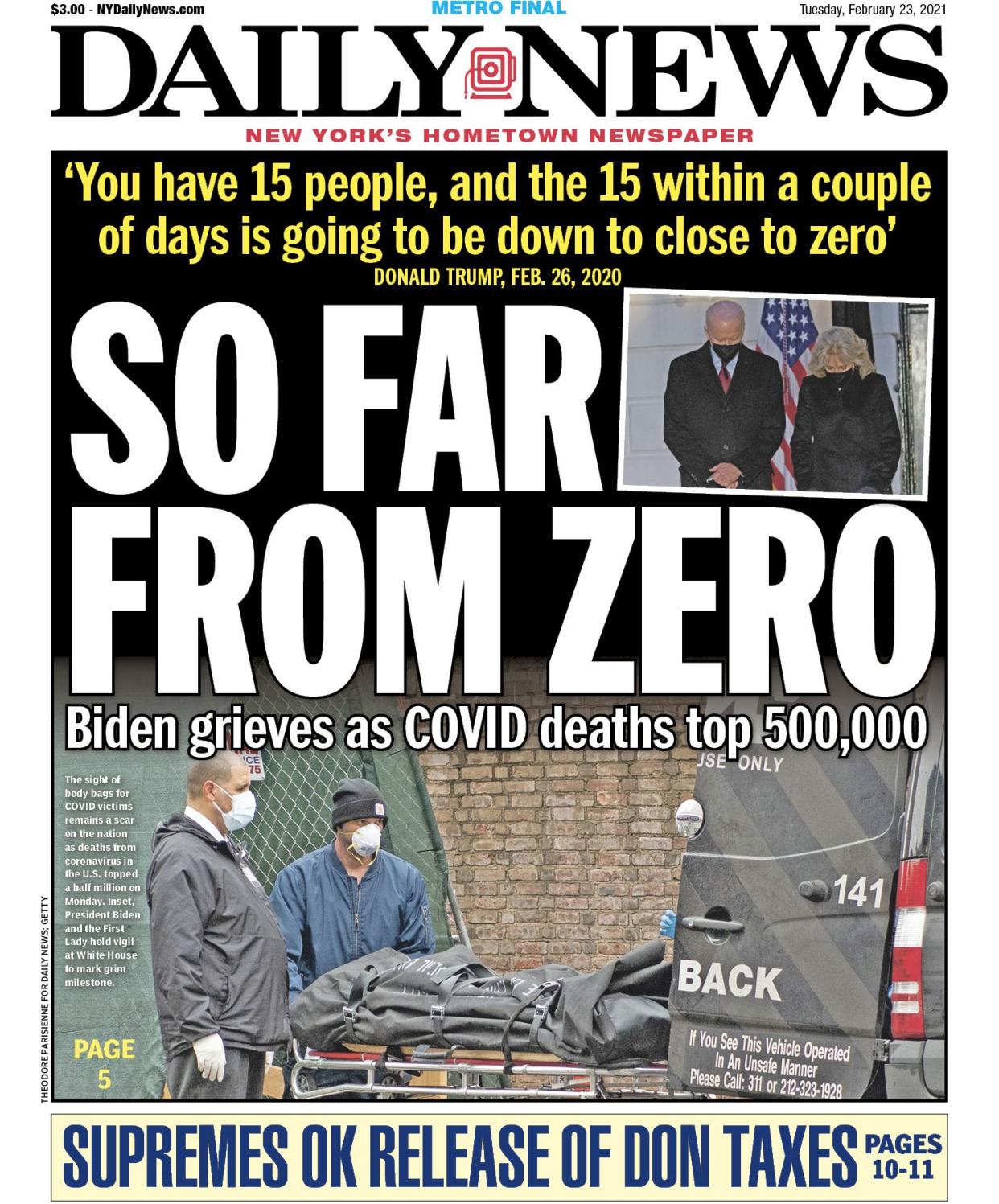

The COVID-19 death toll in the U.S. climbed to a staggering 1 million on Monday — and not even in the darkest days, when bodies were being stacked in refrigerated trucks and New York City’s dead were being buried in mass graves did anyone think this number could be reached.

It took two and a half years since the start of the coronavirus pandemic to hit the grim milestone — and even that figure is low, health experts say. The true count is probably much higher, given the number of people who went undiagnosed.

The 1 million confirmed deaths was according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, based on death certificate data. The total on Johns Hopkins University’s Coronavirus Resource Center stood about 200 deaths shy of a million Monday evening and expected to reach the mark by Tuesday. The average number of daily deaths over the weekend was more than 700.

“It’s unbelievable. I still can’t really wrap my head around it. That’s a million souls in this country, and it’s just so insane,” said Beth Blauer, associate vice provost for public sector innovation at Johns Hopkins University, and the data lead for its COVID resource center.

“Every dot is a heartbreak for us,” Blauer told the Daily News of the data points she and her colleagues have been recording on Johns Hopkins’ coronavirus case map for the past two years. “These aren’t just numbers.”

It was a number, medical experts said, that we didn’t have to hit.

“Number one, we weren’t prepared, nor was anybody else, for an airborne respiratory pandemic, although leading virologists and others have warned about this possibility for a while,” Dr. David Battinelli, physician-in-chief at Northwell Health, told The News. “The second was, we got a slow start with respect to responding to the pandemic and had a shortage of protective equipment.”

While the shortage did not affect Northwell specifically, he said, many other institutions around the country and in New York City found themselves wanting. Then the politicization set in.

“There was an unnecessary amount of political involvement underestimating and downplaying the extent of the possibility of worldwide spread,” Battinelli stated. “And despite the fact that we had incredible response by the scientific community with respect to therapies, and especially the vaccines — which are among the greatest biotechnology achievements — there was not the amount of political alignment to convince people of the need to be vaccinated.”

COVID-19 attacked our bodies and society at their weakest points, proving most vicious to the elderly, as well as those with comorbidities ranging from obesity to cancer to diabetes and cardiovascular problems.

People of color were inordinately hit — Black, Latino and indigenous communities ― partly because they tended to have more comorbidities, and partly because they tended to have less access to medical care.

Coronavirus also felled completely healthy people who were not elderly. Broadway dancer Nick Cordero succumbed to the disease at age 41. Pregnant women lost their babies, or had their babies but lost their lives. Children developed a hyperbolic immune response that inflamed their whole systems.

Conflicting advice didn’t help. First there was the downplaying of the virus itself, out of a desire not to panic everyone. Then a focus on wiping down surfaces. Then, awareness dawned of how airborne the virus was, and the need to wear masks emerged. Lockdowns forced most people to stay home, and the closures of stores and restaurants and theaters.

The disease, dubbed COVID-19 in February 2020 by the World Health Organization, began to take hold. Everyone thought it would last a few weeks. More than two years later, it’s clear they were wrong.

Virtually the entire globe was affected. Brazil is now a distant No. 2 in deaths behind the U.S., with more than 665,200 as of Monday. India is third, at 524,200-plus and counting.

“I don’t think any of us in the early days thought that in 2022 we’d still be managing a daily operation,” Blauer told The News.

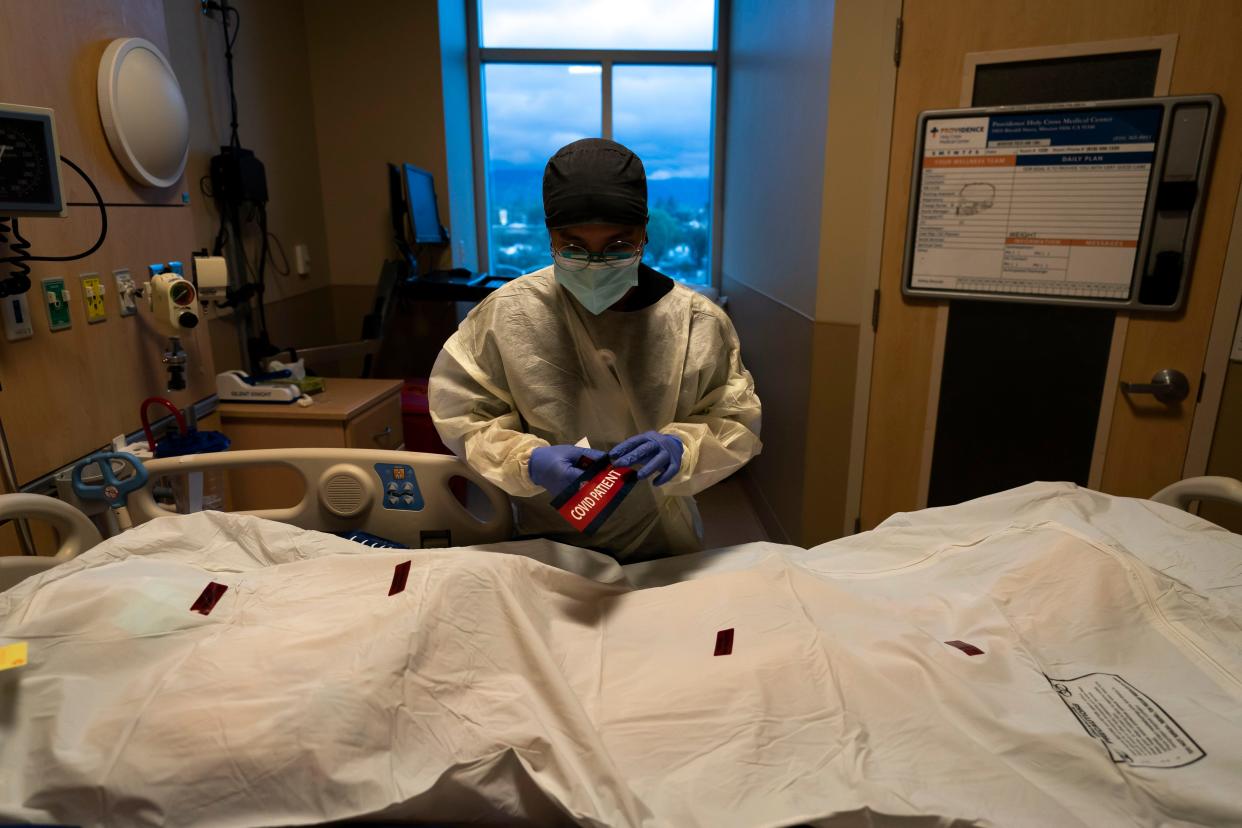

In places like New York City, sirens wailed constantly in 2020. Refrigerator trucks appeared outside hospitals and funeral homes, filling up with bodies. The nightly clanging of pots and pans outside the windows celebrated health care workers’ heroic healing acts — labors that too often turned into bedside goodbyes.

Through it all, essential workers staffed the grocery stores, delivered mail and packages and toiled at pharmacies.

Vaccines came along at the end of 2020. Their groundwork had been laid years earlier, but the specific aim at the coronavirus brought them up to speed quickly. Some felt too quickly.

Combined with misinformation and a host of other sociopolitical issues, plus pushback against mask mandates and other public health measures that medical experts deem to be common sense, the distrust that had been brewing throughout the previous year blossomed into full-scale rebellion.

“The primary problem is the inability to convince enough people to be vaccinated and maintain specific social behaviors,” Battinelli said, which “led to many people becoming sick who hadn’t been vaccinated.”

He repeated what health experts have been saying all along, and what the statistics bear out.

“The data is incontrovertible that people who received full vaccination including a booster had substantially better outcomes than the unvaccinated,” Battinelli said. “So it is the under- or unvaccinated groups who have contributed the greatest to COVID mortality.”

Given that, the coronavirus death toll will not stop after a million.

“There will be many more if the uptake of vaccines is not improved,” Battinelli said. “And for those who want to get back to normal, that is the route to get back to normal.”

The emotional toll the pandemic has taken is only beginning to be apparent, demographer and sociologist Ashton Verdery told The News, based on research he and others are conducting. In October, one study estimated that at least 140,000 children had lost one or more caregivers to the pandemic.

“Our results suggest that when we hit a million, that will mean that 9 million people in the U.S. have directly lost a parent, child, sibling, spouse or grandparent,” said Verdery, an associate professor of sociology and demography at Penn State University.

Blauer expressed concern that many public health departments are scaling back the intense data collection that arose during the worst of the crisis, even though the information could help shed light on a number of health issues, not just the virus.

“Instead of advancing the field, we’re shutting down the operations and trying to go back to business as usual,” she said.

“We can’t prevent all deaths,” Battinelli said. “But you do what you can do, and we have only done half of what we can do.”