Could an earthquake like in Syria, Turkey hit WA? It’s possible. Here’s what could happen

Running 43 miles long from east to west directly below Puget Sound, a weak point on the North American Tectonic Plate is quietly rumbling away.

Two giant pieces of rock, separated by an ancient fracture, are pressed against one another, shifting and sliding in tandem. It’s called the Seattle Fault Zone — it passes directly under Seattle and follows approximately the same path as Interstate 90 — and could one day be responsible for an earthquake resulting in massive destruction and death totals throughout Puget Sound.

That doesn’t mean a ground-shattering earthquake could occur anytime soon — many times, scientific instruments can pick up a weak earthquake that can’t be felt on the surface.

In the past week, earthquakes of around 2.0 magnitude have been detected beneath Birch Bay, Snoqualmie and Bonney Lake, among other places. Earthquakes are measured on the Richter Scale, which ranks an earthquake’s strength from 0 to 10; the lower the number, the weaker the quake, with each unit of 1 representing a 10-fold increase in strength.

As multiple earthquakes continue to cause widespread destruction and loss of life in Turkey and Syria, what are the chances a similar event could happen in Washington?

Chances of a major quake in Washington?

The Seattle Fault Zone has given Puget Sound residents a couple of scares in the past century — Tacoma experienced a 6.7 magnitude earthquake in 1965, and a 6.8 magnitude earthquake struck the south Puget Sound region in 2001.

For reference, the initial quake that struck Turkey and Syria on Feb. 6 — the Kahramanmaras earthquake — was a 7.8 magnitude tremor shortly followed by a 7.5 magnitude quake. A 6.4 magnitude earthquake hit the same region on Tuesday.

“Our chances of a magnitude seven earthquake happening are probably more than people think,” Harold Tobin, director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network and professor at the University of Washington’s Department of Earth and Space Sciences, told McClatchy News.

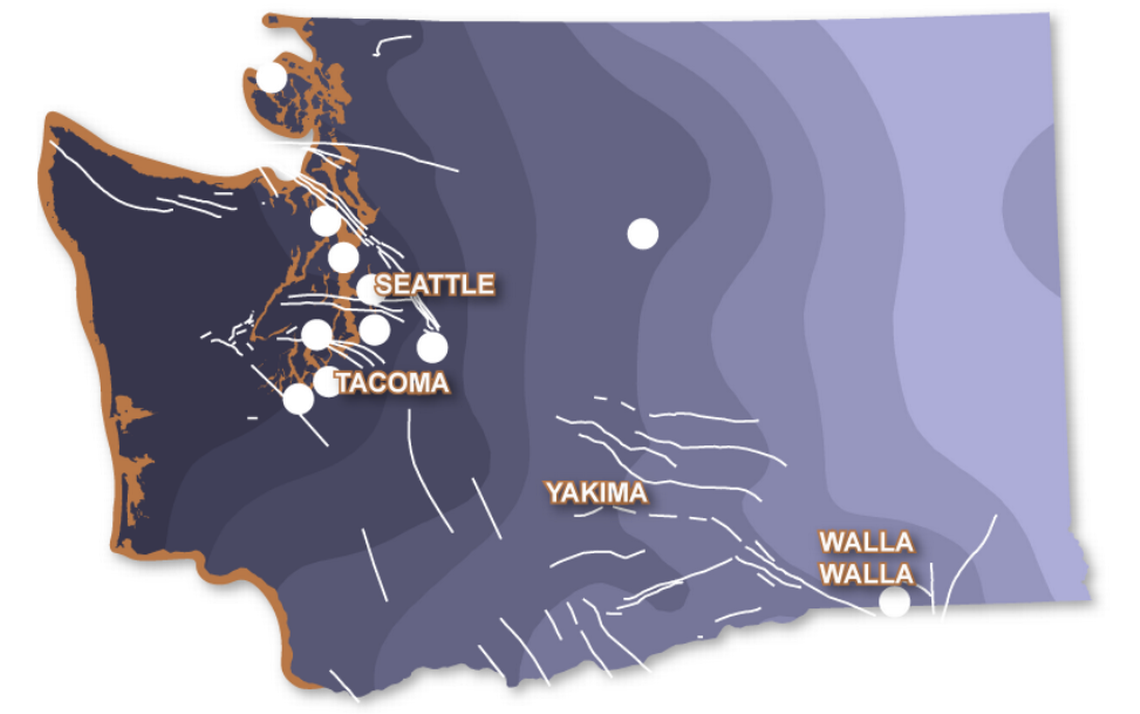

“We have multiple sources of earthquake hazard in Washington,” Tobin continued. “In western Washington more so than eastern, but not to the exclusion of eastern Washington.”

Tobin believes the chances of another earthquake of similar magnitude occurring in the Puget Sound region within the next 30 years stand as high as 80-85%. He notes that the same stat can be relevant for periods as far as 50 or 100 years, but 30 years is used as a benchmark because it’s about the length of a generation and easier for people to wrap their minds around.

The city of Seattle also estimates that an earthquake of 6.0 magnitude or larger occurs every 30 to 50 years. The last one to occur was the 2001 Nisqually earthquake; prior to that event, 6.0 magnitude or stronger earthquakes have occurred around the Puget Sound in 1965, 1949, 1946, 1939 and 1909, according to the city’s website.

Will WA face ‘The Big One’?

While the Seattle Fault is a cause for concern, seismologists are just as concerned about what they call “The Big One.”

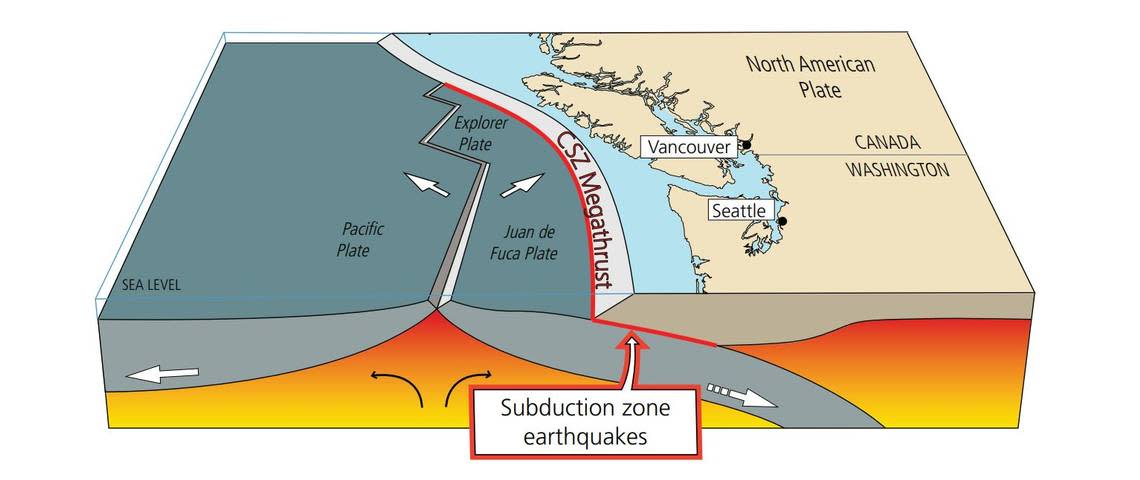

The North American Plate presses against the Juan De Fuca Plate just off the Washington coast. The two plates rapidly move approximately every 300 to 600 years, resulting in a massive offshore earthquake.

The last time it occurred was in 1700 — the Cascadia Megathrust Earthquake, which resulted in an earthquake of approximately 9.0 magnitude.

That was 323 years, putting us in the area period of when the next one will occur.

“I wouldn’t call that overdue, but I would certainly say that the conditions are there for an earthquake to happen on the Cascadia subduction zone,” Tobin said. “And I mean it literally, you know, it could be tomorrow, and it could be 100 years from now.”

What would a high-strength earthquake look like?

Tobin fears the next large earthquake in Washington could cause widespread damage because of the similarities between the Seattle Fault to the North Anatolian Fault which caused the recent earthquakes in Turkey.

“The danger is that the fault runs shallowly in the crust, and that’s what is similar to Turkey,” Tobin said. “The location of the earthquake, what we call the hypocenter, the point down in the earth below that where the earthquake waves originally start to emanate from, is shallow, which is similar to Turkey. And the fault line runs right through the populated region.”

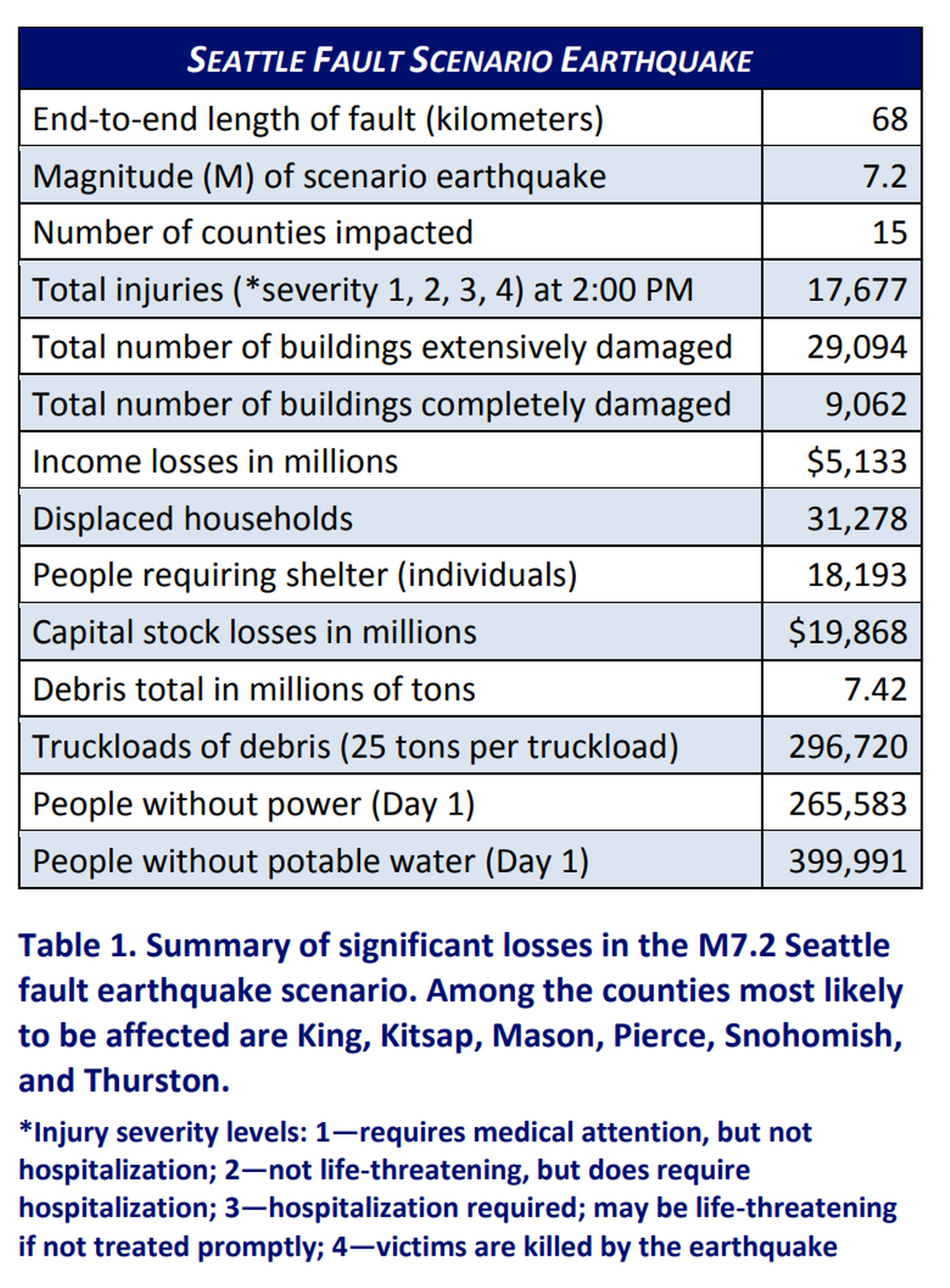

The Washington Military Department has modeled what a 7.2 magnitude earthquake would look like in the Seattle Fault Zone. It estimates that an earthquake of that size would result in over 17,000 injuries immediately following the quake, over 38,000 buildings extensively or entirely destroyed, and ultimately $19.9 billion in capital stock losses.

“We know that we have a mix of buildings and bridges and structures of different ages and different degrees of seismic construction codes that they were built to,” Tobin said.

“Newer ones are likely to be better buildings and stand up better in the event of a big earthquake,” he continued. “But we know that there are unreinforced masonry buildings; there’s more than 1,000 of those just in Seattle alone. We know that there are older concrete structures that probably aren’t built in the same resilient way that we would like to see.”

When the rumbling and shaking stop, that won’t be the end. The threat of a tsunami would follow.

The “Big One” off the coast of Washington could result in waves as high as 40 feet within minutes to a couple of hours after the quake, according to Tobin. The whole west coast of Washington, inland down the Columbia River, and most of Puget Sound from the Canadian border to south of Tacoma and Olympia would experience flooding, according to a map from the Washington Department of Natural Resources.

Similarly, Tobin said an earthquake within Puget Sound would produce a localized tsunami within the sound, with waves of over 10 feet arriving minutes after the quake.

“We don’t know when the next large earthquake is going to strike the area, but it’s inevitable that one will sooner or later,” Tobin said. “We should use the time to do the best job we can — preparing and making our buildings, bridges, and roads more resilient.”