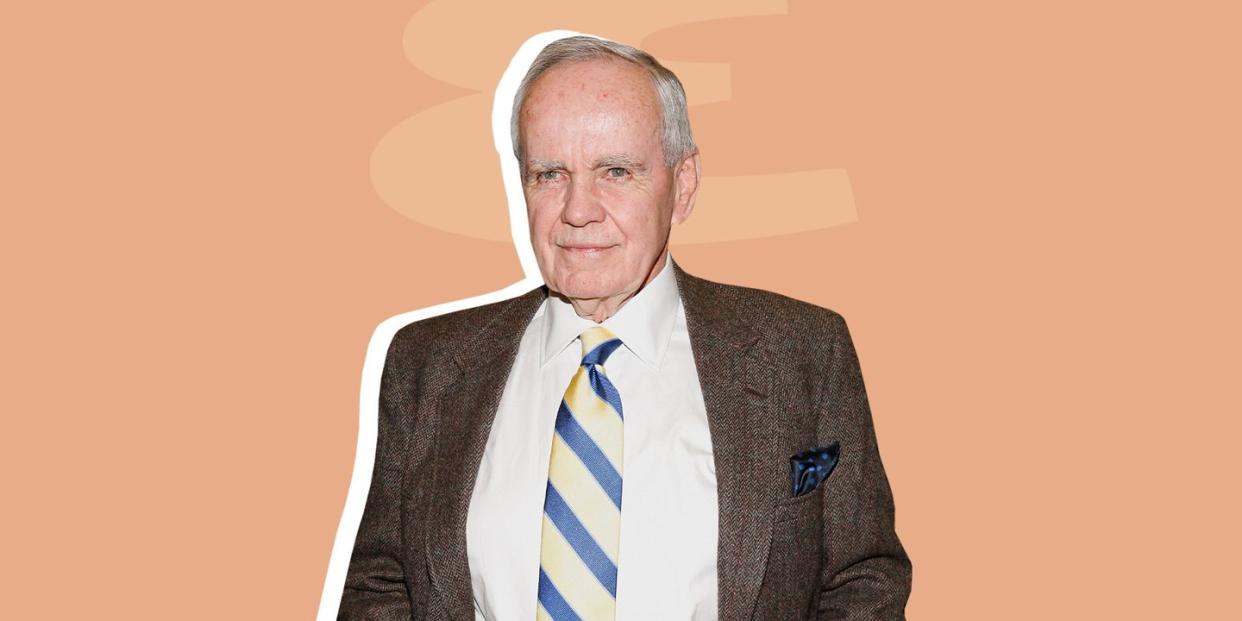

Cormac McCarthy Finally Lays Down His Arms

Cormac McCarthy returns this month. Now 89 years old and one of America’s preeminent writers, he hasn’t released a book since the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Road was published sixteen years ago. But this month, McCarthy reemerges with the first of two new novels, which veer away from the typical Gothic feelings that have inhabited almost all of his work. With the publication of The Passenger and its companion novel Stella Maris, McCarthy seems to be done mining the myth of America. Instead, he ponders what it means to exist, and what our history tells us about our future.

In years since The Road, the famously reclusive author wrote a screenplay for a Ridley Scott movie called The Counselor and edited a biography of physicist Richard Feynaun by Lawrence M. Kraun, but that wasn’t something he told anyone—we only found out by way of the book’s acknowledgements. He joined the Santa Fe Institute as a research fellow alongside some of the brightest minds in physics. In 2017, he published a nonfiction essay about "the unconscious and the origin of human language,” for Nautilus, which came out of his study at the Institute and shares many of the same themes of his new novels.

Otherwise, the little noise about McCarthy didn’t come from him. There’s been a pair of Twitter impersonators, a Paris Review April Fools “interview,” and an unverified death announcement that went viral, only to be debunked soon after. In that time, McCarthy worked on a pair of connected novels about a smart brother and genius sister whose lives are entwined through a mutual but forbidden love, as well as through their shared history as the children of a father who worked on the Manhattan Project. The Passenger will be released on October 25 and Stella Maris on December 6, when a box set of the two novels will also be available. In the pair, McCarthy avoids, for the most part, his usual fascination with man’s desire for violence and our nihilistic pursuit of meaning. Instead, he digs into the big ideas of the universe, like human existence and what it means, as well as what our history and memory mean. He’s searching for something different.

But to put the new novels into context, we need to go back in time.

In 2006, McCarthy reached the peak of literary fame. He released The Road, a dark and frightening love letter to his young son. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and Oprah Winfrey selected it for her immensely influential book club. The notorious recluse even granted her an interview—on his terms, of course. Winfrey, who doesn’t have to go anywhere for anyone, flew to sit across from the writer at the Santa Fe Institute, asking him questions like, “Did you always know you’d be a writer?” McCarthy, slouching in his oversized chair, leaning on his arm, gave strange and wonderful answers that only a writer so sure of himself could give. When Winfrey asked about his writing process, McCarthy paused and replied, “I don’t think it’s good for your head if you spend a lot of time thinking about how to write a book. You probably shouldn’t be talking about it. You should probably be doing it.” At the time, that felt prescient. He’d just released two books in a few years and seemed as productive as ever. Then, he went silent.

While McCarthy had enjoyed success in the past with All the Pretty Horses (which was also adapted into a movie and won the National Book Award), he was still a writer who skipped mainstream success. His previous novel Blood Meridian was considered one of the great American novels of the twentieth century, but its brutality didn’t make it an instant bestseller. To put it lightly: he’d never before had the social or financial cache that The Road brought. He was on top of the world, and everyone was waiting for what would come next from a writer who’d delivered some of his most personal work yet. The detached narrator of the past still lived, but somehow, it gained a bit more soul with The Road. He’d grown into a quasi-optimist by the end of the book, which still shocks and amazes readers to this day with its apocalyptic outlook and open-mindedness. At the end of The Road, hope peeks out of the darkness.

At the same time, McCarthy’s 2005 novel No Country For Old Men received the Coen Brothers treatment in 2007. The film won four Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay. After that, though, McCarthy vanished. No book. No push towards more fame. Meanwhile, his competitors for the title of “best living American author” began to accept the limelight: Philip Roth hired a biographer, while Don DeLillo wrote more and saw his work adapted on screen. McCarthy left us to wonder where he’d gone and to examine what he’d left behind, searching for clues in the work.

What’s separated McCarthy from his contemporaries is his restraint. He avoids telling the reader how to feel. In fact, he does the opposite. At times, McCarthy has strayed so far from feeling that it makes the matter-of-fact violence in some of his early work, especially his 1985 masterpiece Blood Meridian, feel more sinister. The author’s detachment is juxtaposed with men (always men) seeing something horrific as they ride across the open plains of the American West. When the kid and one of his travel partners come upon a tree of dead children in Blood Meridian, we’re left to see the dead and feel for them as the characters wander past:

“They stopped side by side, reeling in the heat. These small victims, seven, eight of them, had holes punched in their underjaws and were hung so by their throats from the broken stops of a mesquite to stare eyeless at the naked sky. Bald and pale and bloated, larval to some unreckonable being. The castaways hobbled past, they looked back. Nothing moved.”

There’s no escaping the image. There’s no letting go. It stays because McCarthy stands back and doesn’t interject. We know how the children got there—murdered by settlers slaughtering Natives and Mexicans, ravaging the landscape as they head west—and we know the kid knows, too. That’s enough for McCarthy. He moves on. The characters (and life) need to continue.

McCarthy’s apocalyptic style, which has been described as “biblical,” can trouble readers because he won’t tell you who to root for, even if as we read, we know. He refuses to tell us how to feel. Finishing Blood Meridian is a slog not because of the story or the writing, but because of how it refuses to let up on the haunting details. I read the novel four times in the span of a few months last year for graduate school and it lived with me in my dreams. The book makes you relive each violent step of American history and doesn’t leave you feeling like anything will get better. How can it?

America’s infatuation with violence and how it has shaped us has proven to be compelling material for McCarthy. Violence is life. It’s the fabric man has clothed himself in for all of his existence. Until The Passenger and Stella Maris, which take the author down new thematic journeys, violence is how McCarthy has connected to and understood the world. From the beginning of his writing career, he's spent his time in the dark trenches of America, focused on how violence has shaped us.

"There's no such thing as life without bloodshed. I think the notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea,” McCarthy told Richard B. Woodward in a 1992 profile for The New York Times. “Those who are afflicted with this notion are the first ones to give up their souls, their freedom. Your desire that it be that way will enslave you and make your life vacuous."

The study of human suffering and violence has dogged McCarthy from the outset of his career, beginning with his first novel, The Orchard Keeper (published in 1965), all the way through The Road. That obsession with violence and its matter-of-fact presentation on the page became McCarthy’s calling card, but it also left some critics to wonder if we were missing something. According to some, McCarthy continued to refine his prose while forgetting his character’s feelings about the horror they’d witnessed. Did it always have to just be? In 2005, the critic James Woods wrote in The New Yorker, “McCarthy's idea—his novelistic picture—of life's evil is limited, and literal: it is only ever of physical violence. Though one wouldn't want to turn McCarthy into Henry James, there are surely ways to use a novel to register the more impalpable forms of evil and violence as well as the palpable.”

Woods wants some sentiment for the violence, some understanding. He wants the writer to go a bit deeper on the page, with more internal struggles appearing. At first, the kid in Blood Meridian is our guide; like him, we get sucked into the story of John Joel Glanton’s gang and Judge Holden, abandoning our morals to follow a band of terrible people that scalp and hunt Natives. We, like the kid, are seduced. For Woods, that’s not good enough. He wants the novel to go harder into why we’re seduced. He wants revelation and change. Eventually the kid escapes, but it’s too late. We’ve lost the chance to see his struggle. McCarthy has no interest in that, which is what makes the book so haunting. He knows what he’s doing. By the time we catch on, he has too, and he moves the story another step. He makes us ponder what we’ve seen. Would we feel any differently if we were there? But with his new novels, McCarthy has gone in a different direction.

The Passenger and Stella Maris explore Bobby and Alicia Western’s minds—more specifically Alicia’s. Here McCarthy uses the siblings to parse out more than human nature’s desire for violence. He’s parsing out where we fit into the world—if there is even a world or time. He’s trying to come to grips with what he’s spent his time learning about at the Santa Fe Institute: the nature of the universe through the study of physics. These novels focus more on the internal than anything McCarthy has done in the past, but instead of writing a book about an old man looking back on the events of his life, like some of his fellow Great American Writers might have, McCarthy chooses a sibling duo who are in love with each other and too smart for their own good. While Bobby goes off on a journey trying to make it through life, Alicia talks to a therapist about what it means to exist while contemplating suicide. Where other writers venture into the mind and soul, McCarthy has leapt past that to ask what a soul is—and if it even exists.

There were hints that McCarthy had been working on something since finishing The Road. He talked about the book with The Wall Street Journal in 2009: “I'm not very good at talking about this stuff,” McCarthy said when asked about what he was working on. “It's mostly set in New Orleans around 1980. It has to do with a brother and sister. When the book opens she's already committed suicide, and it's about how he deals with it. She's an interesting girl.”

Thirteen years later, that book has become the pair of intertwined novels that are about Alicia and Bobby Western, but they’re concerned with nuclear bombs and physics (the Westerns’ father is a physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project). Mostly, though, they’re about humankind’s place in the ever-expanding and never-ending unknown.

The Passenger, which comes out first, tells the story of Bobby Western, a salvage diver who stumbles on a mystery involving a sunken plane and a missing person. It sends him searching for answers about his past while running from some unknown arm of the government that won’t let him just be. At the same time, he tries to understand how he ended up here, and how and why his younger sister ended up dead. In typical McCarthy fashion, Western goes on a journey, venturing from one southern location to another—like Mississippi, New Orleans, a Florida oil rig, and other eastern locations that haunted much of McCarthy’s early novels and life. Along the way, he enters bars, restaurants, and the swamps, trying to reconcile his past through his memories and trying to understand his future through what others tell him. But more than anything, this is McCarthy trying to reason with God. The Passenger is another story of a roaming soul looking for answers about how the universe works. “He thought that God’s goodness appeared in strange places,” McCarthy writes after one of Western’s meetings. “Dont [sic] close your eyes.” (McCarthy’s fun punctuation is included here). The world Bobby Western sees is far from the world to which he belongs. The only way to connect the clues is to dig deeper. Where that takes him connects him to his past, giving him only breadcrumbs of hope and large slabs of despair. In the end, what comes is inevitable. It’s his family’s legacy.

The second novel, Stella Maris, contains a bigger leap for McCarthy: a female protagonist. “I was planning on writing about a woman for 50 years,” McCarthy told The Wall Street Journal. “I will never be competent enough to do so, but at some point you have to try.” And try he does, but by avoiding writing anything that resembles a traditional novel. Instead, it’s one long conversation between Alicia Western and her psychiatrist at the Stella Maris psychiatric facility in Wisconsin. In the typical McCarthy fashion, it’s mainly punctuated thoughts roaming in free-flowing soliloquies. Alicia is a brilliant mathematician who’s lost her grip on reality as she reels from seeing her brother in a coma after a racing accident. She’s lost in more ways than one, untethered by her inability to share the kind of passion and love she wants with Bobby. She believes he’s dead, but what is death to someone who doesn’t see the universe by the same rules as the rest of us? When pressed about her memory by the psychiatrist—“We’re all of us pretty much an assemblage of memories”—she counters with what can only be the deepest sentiment McCarthy has ever written: “I suppose I trust my memory of events largely because of the evidence I have for my ability at memorization. Are they the same? The lines of a poem have no substance other, but the events of history—including your personal history—have no substance at all. Their materiality has vanished without a trace.”

McCarthy’s characters constantly cross borders, literally and figuratively, in search of themselves, but more importantly in search of their place in the changing world. Even McCarthy’s other books, with their vile characters and vile plot points, are always about people searching. The Border Trilogy, most specifically The Crossing, is about people looking for their place in the world and trying to understand how humans can be so cruel. To Woods, McCarthy’s work often has no end game. "McCarthy's fiction,” Woods writes in The New Yorker, “seems to say, repeatedly, that this is how it has been and how it always will be.”

But for McCarthy, the new novels show evidence of a transformation. He’s begun to see the world not as a place that changes around us, but rather as a place where everything is connected and made up of our shared history. With each change comes the next iteration of life. These ideas are more present on the page now, but the big idea was always there.

There’s a passage in Blood Meridian that has always stood out to me, early in the book when the kid is roaming in search of a life. He comes across an old hermit, who says:

“A man’s at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with. He can know his heart, but he don’t want to. Rightly so. Best not to look in there. It aint the heart of a creature that is bound the way that God has set for it. You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything. Make a machine. And a machine to make the machine. And evil that can run itself a thousand years, no need to tend it.”

McCarthy is no longer searching in the dirt trail across the West and saying, “This is it. This is our human nature.” In The Passenger and Stella Maris, he’s trying to see the God that made the man who wrote those words. While the novels might not click in the familiar way that old ones do, they’re something invigorating about an author expanding on his view of the universe as he inches closer to his own conclusion.

You Might Also Like