The comic-book movie so bad it made Sean Connery quit acting: ‘His passion had left him’

I’m fed up with the idiots,” Sean Connery once said, upon announcing he was quitting Hollywood. “The ever-widening gap between people who know how to make movies and the people who greenlight the movies.” This was in 2005, two years after the release of what would end up his final film: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a comic-book adaptation so cursed that the history-making floods that derailed its production may have been nature’s way of telling everyone involved that trouble was afoot.

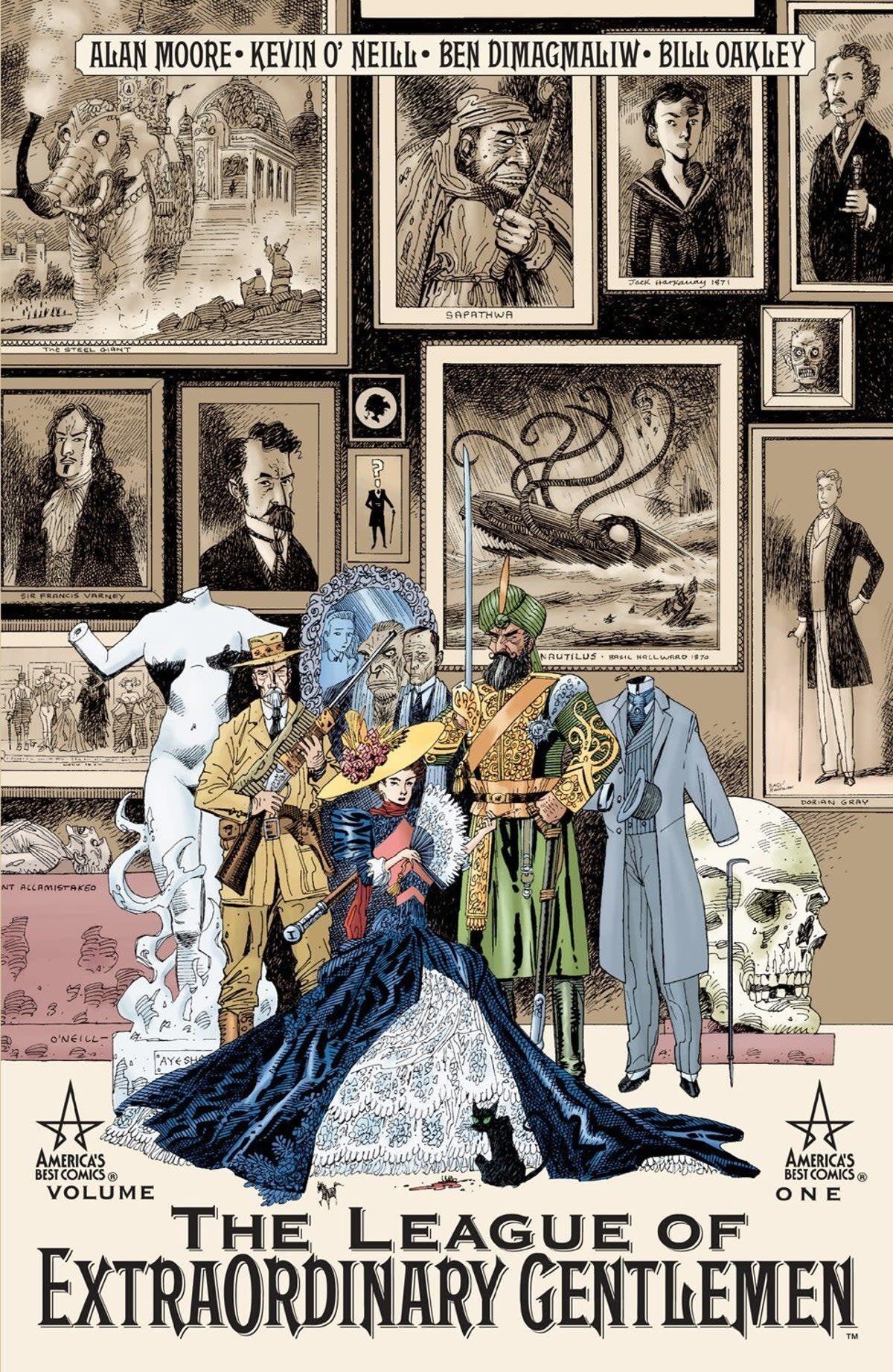

It’s been 20 years since the League assembled, Avengers-style. That was the idea, at least. Based on the comic-book series by writer Alan Moore and artist Kevin O’Neill, it’s a riff on the traditional superhero team-up story. But instead of superheroes, The League is comprised of a collection of Victorian literary characters, all of whom band together to save the world. Like The Avengers, the film was also an attempt at kickstarting a mega-franchise. But due to its troubled journey to the screen and all-round critical shoeing, it never happened.

In LXG, Connery plays League leader Allan Quatermain, the colonial adventurer from King Solomon’s Mines. The film’s final showdown sees him fight to the death with Professor Moriarty (Richard Roxburgh), the arch-nemesis of Sherlock Holmes, but the real battle was happening behind-the-scenes, and between Connery and director Stephen Norrington (who previously directed the well-received Blade). As reported in a set visit by Entertainment Weekly, tensions between the star and his director almost came to fisticuffs, after Norrington shut down production for an entire day – because he didn’t like an elephant gun prop. The 72-year-old Connery – a long-tenured, formidable star who did not like to be kept waiting – was “livid” and threatened to get the director fired. Norrington challenged Connery by screaming, “I’m sick of it! Come on, I want you to punch me in the face!”

Big words, of course. This was Sean Connery – 007 himself. The man who broke out of Alcatraz (and then back in again) in The Rock, who took on Al Capone in The Untouchables, who pilfered the Soviets’ best nuclear sub in The Hunt for Red October – the man whom League co-star Jason Flemyng tells me he always called “Big Sean”. As an unnamed friend of Connery’s said to the New York Daily News: “If they came to blows, do you think Norrington would be alive?” Flemyng – who played Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in LXG – sums up the Connery vs Norrington feud more delicately. “Big Sean and the guv’nor were not getting on great,” he laughs.

Though tensions were high, actor Stuart Townsend – who played the LXG’s best, smarmiest character Dorian Gray – never saw any of the well-reported bust-ups. “Whenever I was on set, everyone was having a great time,” he tells me. “As I’d go, or just before I arrived on set there’d be a huge fight.”

The original LXG comic was first published in 1999. Film producer Don Murphy heard about it while on the phone to Alan Moore himself. At the time, Murphy was developing another adaptation of Moore’s work – his Jack the Ripper graphic novel, From Hell, which would ultimately be made with stars Johnny Depp and Heather Graham. Moore – who also wrote the seminal Watchmen and V for Vendetta – is notoriously grumpy about adaptations of his comics (“I would be the last person to want to sit through any adaptations of my work,” he told GQ last year. “From what I’ve heard of them, it would be enormously punishing.”) Still, Murphy took the idea to 20th Century Fox. The studio head loved it. “It became this project that you always knew was going to get made because the idea was such a crazy but original good one,” Murphy said in a making-of documentary.

Like Moore’s other work, there is an air of highfalutin smugness about the original comic. Though it’s brilliant, of course – rich with commentary on colonialism, suffragettes, industrial scale arms, and 19th-century sleaze. The film version, adapted by British comics writer James Robinson, was inevitably dumbed down – a by-the-numbers, getting-the-band-together origin tale. This was a time when the average CGI-powered blockbuster was only as deep as its new-fangled computer effects. And lots of them were very average in the late Nineties and early Noughties: the Mummy films, Wild Wild West, Pearl Harbor, Men in Black II and the Star Wars prequels, to name just a handful.

After the premiere, my thought was, ‘Jesus, was that really worth six months of my life?’

Stuart Townsend

In LXG, the League must stop Moriarty (masquerading as “M” in a bit of gimmicky post-modernism) from starting a world war. “There will be others like me!” he warns, marking himself as an OG Hitler. The movie League consists of Allan Quatermain (Connery), Dracula’s would-be bride Mina Harker (Peta Wilson), the split-personalitied Jekyll and Hyde (Flemyng), a crafty, cockney Invisible Man (Tony Curran), Oscar Wilde’s immortal hedonist heartthrob, Dorian Gray (Stuart Townsend), and the legendary submariner, Captain Nemo (Naseeruddin Shah), of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Fox couldn’t secure the film rights to all the characters from the comic. Fu Manchu was dropped and The Invisible Man became an average, run-of-the-mill invisible man, not the specific one from the HG Wells book. To appease American cinemagoers, classic literary hero Tom Sawyer (Shane West) was also added to the line-up. There was some grumbling at the time. It’s a peculiarly British irritation: studios changing things to pander to American audiences (see also, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone becoming “The Sorcerer’s Stone”, or Americans muscling in on The Great Escape).

Connery, even on promotional duties, didn’t seem bothered about joining the League. “At first I didn’t fancy it,” he admitted in a making-of doc. “I thought it was a little too tricksy”. For Connery, it was also too much like the effects-heavy Lord of the Rings and Matrix films, both of which he was offered and turned down. Connery didn’t understand any of them. LOTR may have actually been a factor in Connery accepting LXG. Asked to play the role of Gandalf in exchange for a share in the film’s profits, he missed out on an Eye of Sauron-watering $350m. Connery didn’t miss out this time: he was paid an impressive $17m for LXG. “Big Sean was paid a lot of money but wasn’t massively interested in making films,” remembers Flemyng. “He wanted to be playing golf.”

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen certainly had money-spinning potential. Comic book movies were the hot new trend, and director Norrington should have been a sure bet. His Blade was – Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man films aside – the slickest of the pre-MCU Marvel movies. LXG was also a major production, costing a reported $75-$95m. Based mainly in Prague, the production built recreations of Venice – “brick-by-brick” says Flemying – and Nairobi, with livestock, actors, and everything else flown in. “The size of that film… it was the kind of thing I always dreamt about making,” he adds. But that came with big problems. “This was a big studio movie with a lot of interference and a lot of politics.”

Twenty years on, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen doesn’t live up to its bad rep: it’s not quite that bad, and certainly no worse (though no better) than any number of CGI-powered studio films from the time. It whips through clunky lines and clichés, always rushing to get to the next punch-up, but it has good instincts for practical effects thanks to Norrington’s SFX background and a strong team. “There was no area of that film where the talent was lacking,” says Flemyng. “They were paying the best money – everyone was the best they could be.”

The most impressive creation is Flemyng’s Mr Hyde – a 45lb full-body suit made from eight main parts, 6,000 components, and animatronic hands. It took seven hours to get Flemyng suited up. He recalls getting into the Hyde gear for the first time and being surrounded by producers. “They were all looking at me going, ‘It’s amazing!’” he says. “I said, ‘I’ve got one question – how do I go to the toilet?’ Everybody looked at each other and said, ‘We didn’t think of that…’”

The Jekyll/Hyde transformations are the film’s best bits – he is a discombobulating, juddering monstrosity – and in the spirit of what LXG should have been: an image of old-school horror leaping out from the shadows and grime of the Victorian era.

The production had a major problem, though, that went beyond politics and fallings out: the weather. Following weeks of intense rainfall across Europe in the summer of 2002, Prague suffered its worst floods in a century. The floods destroyed $7m worth of sets. Connery fled his hotel amid the chaos and only managed to rescue his golf clubs. “Ironically, our submarine set was 13 ft underwater,” Townsend says.

“We lost all our sets, we lost everything,” adds Flemyng. “Financially, that was a huge bind. We had to leave everything and go to Malta – to spend way too long on bits that weren’t scheduled to be filmed yet – while they rebuilt the sets in Prague.”

“When we came back it was like another production,” says Townsend. “No one knew what was going on, there was no finish date. It was like doing two movies.”

As for the alleged star vs director feud, Connery described the friction to The Scotsman while the film was still in production. “There have been differences of opinion about almost everything,” Connery said. “Professional differences, personal differences, you name it. But my philosophy has been to shoot the movie and talk about right and wrong afterwards. To be honest, I just want to complete the picture. That’s all I want right now.”

So, what was the problem? A matter of respect, perhaps, between an old-timer who liked things done a certain way and a young hotshot? Townsend recalls Norrington being “a total rebel” and “a total ‘f*** you, Hollywood’ guy. But an amazing director.”

“I think Big Sean’s instincts were right and deserved to be listened to,” says Flemyng. “On the other side, I think Norrington was really creative and a really huge character – he’s a filmmaker and he had an opinion. And it was important that his concept for how it should be was listened to. I don’t think either of them were listened to enough – by each other or by the studio.”

According to reports, Norrington only supervised the editing on a small portion of the film. Connery, however, got stuck into post-production, trying to knock the film into the best possible shape. Editor Paul Rubell was credited with getting the final cut over the line. Norrington was also absent from the premiere at the Venetian casino in Las Vegas. Connery looked like he was having a blast, arriving at the Venetian in a gondola. He also took some more jabs at the director. When asked where Norrington was, Connery quipped, “Have you checked the local asylum?” After repeated questions about Norrington, Connery said, “Ask me about someone I like, will you? … Everyone else in the film was a pleasure to work with. Not him.”

Certainly, the cast had fun with Connery. “Big Sean couldn’t have been more lovely,” says Flemyng. “He had the devil in him and a twinkle in his eye.” Townsend enjoyed the experience but recalls his reaction to the film at that premiere: “My thought was, ‘Jesus, was that really worth six months of my life?”

Critics were similarly unsure. “It’s just so silly you have to like it – sort of,” wrote The Guardian. “But once the novelty wears off, you are left with a very over-egged pudding low on real thrills.” The Independent called it “one to avoid… silly, inept and very ordinary”. LXG performed strongly the first weekend of its release and made an eventual $179.3m – not a disaster. Needless to say, a sequel – which is teased in the film’s final scene – never happened. “Big Sean wasn’t up for that,” says Flemying.

But did it really make Connery quit acting? “I don’t think that’s true,” says Townsend. “His passion had definitely left him by that stage. That was a money gig.” It is true, though, that Norrington hasn’t directed a feature film since.

The problem with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, perhaps, is that it’s all premise and no substance – a tag-along with the latest trend in formulaic filmmaking.

“With all films that don’t work, you’re not emotionally connected,” says Flemyng. “I think that was the problem with LXG.”