Column: Remembering the Bedouin nomad who gave me water in the Negev Desert

I receive many emails from readers saying something like, “Your columns are a breath of fresh air. I need a break from world news.”

To my much-loved supportive readers, this time I can’t offer you that break. I always speak to you from my heart. Today is no different.

I’ve been to Israel twice. During one visit, when I was 21 in 1972, I lived on a kibbutz for a month, then traveled the country for two months.

As my plane approached its landing, I could see the land of Israel. In unison, the passengers sang the Israeli national anthem: Hatikvah (the hope). Although I no longer follow the religion’s practices, I somehow identify as a Jewish person. So, as people sang: Lih-yot am chofshi b’ar-tzeinu, which means: to be a free people in our land, I felt ― I don’t know, a sense of belonging maybe.

You see, all Jews everywhere are Israeli citizens by right. (I confirmed this from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website.) But along with that sense of place comes separation. Suppose I was to think ― Israel belongs to the Jewish people. Everyone else get out.

When I arrived by bus at Kibbutz Evron in northern Israel near the Lebanese border, I was directed to place my feet so that they were exactly in the same sandy footprints of the person before me. This was because there were landmines.

In Israel, my insidious seeds of prejudice began to sprout. And like most prejudice, it was based on fear. I grew scared of “others” ― meaning people who are not like me, in whatever cockamamie way I decide is different, be they of Arab descent, or a male, or young, or even tall.

On my first night, a kibbutznik named Reuven took me on a walk. We were circled by eight men on motorcycles who were speaking in Lebanese, which my new friend translated to me in whispers. They were threatening to rape and then kill me.

Apparently, my partner spoke words that stopped them from attacking me. Essentially, he agreed with them that the American woman would be a luscious prize. He did that to protect me. If he hadn’t agreed with them, or if he fought back with threats, that would have escalated the terror.

And so, that was the beginning of, I hate to admit, my fear of all people from Lebanon.

On a kibbutz, all roles are in a continual state of flux. Someone who’s a cook one day could be a farmer the next. Children live in their own cooperatives although they spend time with their parents in late afternoons.

I remember being tested ― oh was this awful! I was assigned to be a butcher. On my table in the kitchen was a half of a cow. Nobody thought I could handle the job of cutting apart this cow to make individual cuts of beef.

I didn’t breathe through my mouth. With enormous determination to override my disgust of what seemed to be the same as cutting human flesh, I sliced. And sliced and sliced.

Yes, I passed that test. So, I was then assigned to watch over the kindergarten children. They had tubs of creamed chocolate ― spreadable like margarine ― to slather on rye bread. The children didn’t speak English and my Hebrew is limited. But I’ll tell you; the satisfaction noises of “um” and “ah” didn’t need words.

Reuven did a horrible thing. One morning, while I was still asleep in the women’s quarters, I heard him talking in Hebrew with other men as they stood at my bed. I was mortified. I kept my eyes closed. I didn’t know what he was saying, but I heard my name. It turned out he’d also have these conversations during meals in the communal dining hall.

Another kibbutznik took me aside and told me that Reuven was intending to humiliate me by inventing sexual exploits he and I were supposedly engaging in. His cohorts believed every word of it. So did the rest of the kibbutzim.

Now, since it took just a small group of Lebanese men for me to become biased against everyone from Lebanon, wouldn’t I then develop a bias against every kibbutznik? But I didn’t. Talk about unfair favoritism toward Jews, another form of prejudice.

I abruptly ended my stay at Kibbutz Evron and spent months exploring the country.

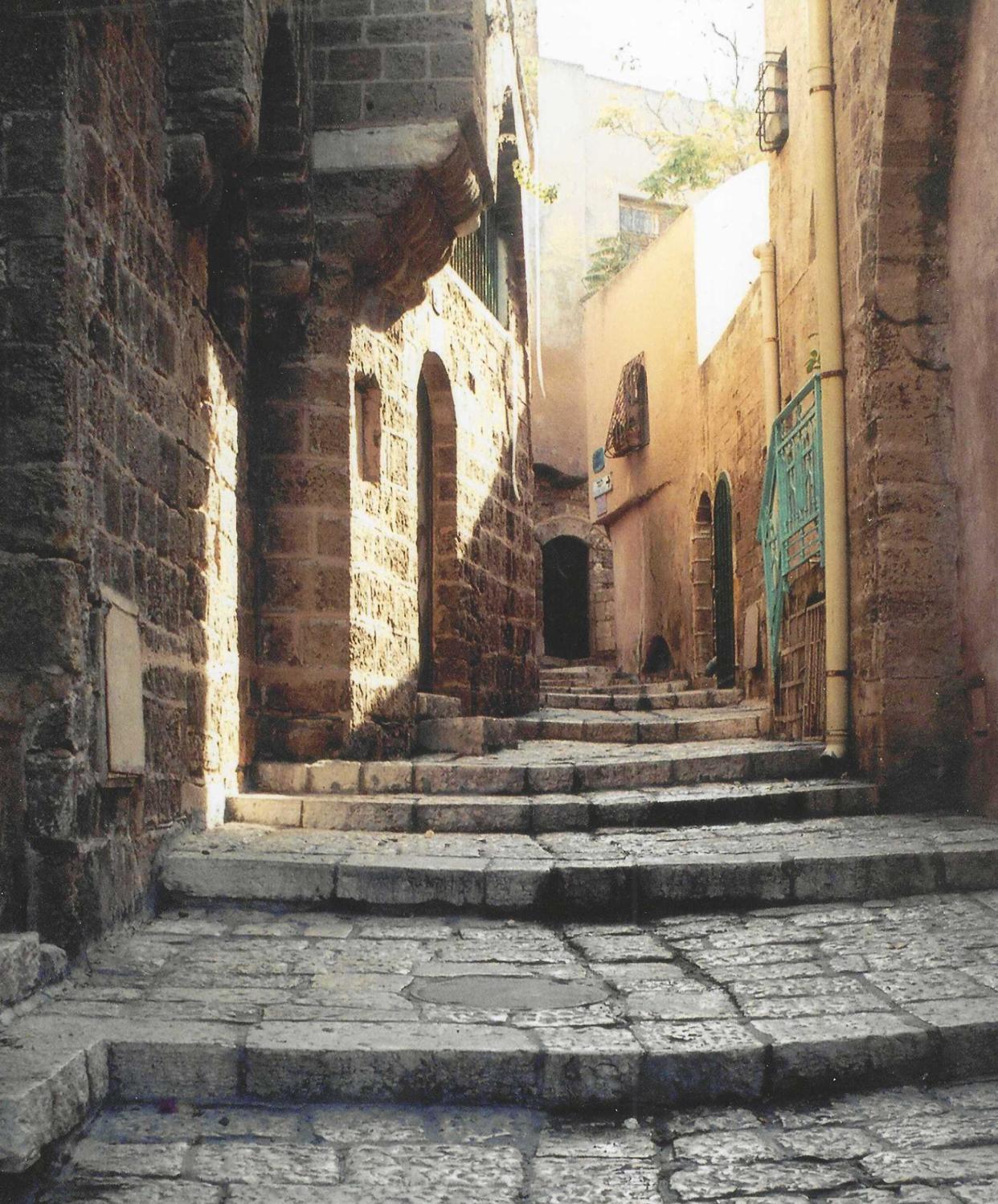

One night, I was at a little bar three floors above a market in the ancient walled city of Jerusalem. It was dark and smoky, with people of various Arab heritage. There was one fellow dressed in a long white robe who seemed non-aggressive. You see my prejudice? My assumption must have been that all people of any Arab ancestry were aggressive.

He didn’t speak English, but we shared the vocabulary of playing gin rummy. We drank shots of arak ― a brandy that tastes like licorice (ick) until late into the night. He had a machine gun by his side.

I slept in hostels ― bare-boned small buildings with cots. Before falling asleep, I’d count the number of scorpions on the ceiling. Small hatchets were stored by every bed.

I hiked along the Negev Desert and Mount Sinai. There was no vegetation — just rocks. The biggest drag? No Ladies’ Rooms. Just stone slabs. Oy.

I saw what’s called “harems” of wild horses. Camels too. On occasion, there were groups of Bedouins, nomadic Arabs of the desert, all dressed in long black robes. Oddly, I was not afraid of these travelers. One woman offered me water from a carved-out gourd, which I gratefully accepted. No English was spoken. Kindness doesn’t need to be put into words.

The first step to toning down my biases is to be aware that I have them in the first place. If I don’t come clean and acknowledge my prejudice, then I’m just a racist.

I hope that someday when I meet someone of Arab descent, instead of thinking about the Lebanese motorcyclists, I’ll remember the Bedouin nomad who gave me water.

Award-winning columnist, Saralee Perel, lives in Marstons Mills. She can be reached at: sperel@saraleeperel.com. Her column runs the first Friday of each month.

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: Column: Remembering the Bedouin woman who gave me water in the Negev Desert.