College now a possibility for more incarcerated Ohioans with Pell Grant reinstatement

Justin Thatcher slid his hands underneath a thinning sheet of pasta dough as he fed it through a KitchenAid mixer. After running it through a few times and thinning it to his liking, Thatcher switched out the extruder for a cutting attachment and transformed the dough into squiggles of fresh pasta.

Eleven women in hairnets and light blue shirts with mint green collars looked on as Thatcher threw the pasta onto a baking sheet and dusted it with flour.

"Alright, who wants to make pasta?" Thatcher, a chef and culinary instructor at Sinclair Community College near Dayton, asked his students at the Ohio Reformatory for Women in Marysville, Union County, who are studying culinary entrepreneurship through Sinclair.

Violet Valdez quickly shot up her hand and took turns with another woman, repeating the process until they'd made their own fettuccini.

For the first time in nearly 30 years, incarcerated people across the country are able to use federal Pell Grants to attend college behind bars.

In 2020, Congress passed the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Simplification Act, which, among other things, reinstated access to Pell Grants for people in prison to pay for higher education. The change, made official in July, allows incarcerated people enrolled in an eligible prison education program to access federal financial aid through the Pell Grant program.

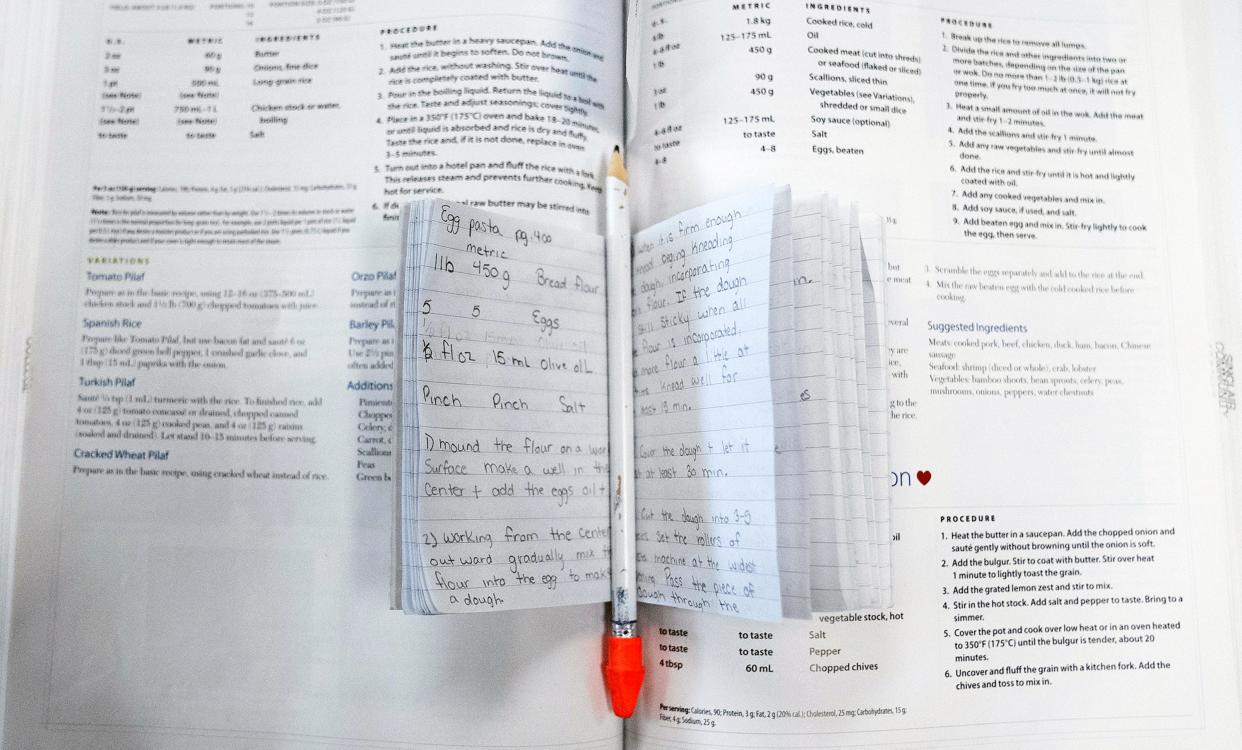

Valdez, 30, didn't grow up cooking, but she did a lot of watching. She frequently references a small notebook where she takes her class notes for answers to questions like, "How long should I boil homemade pasta?" and "How many times do I run dough through the extruder?"

Thatcher gives them to all his students; it's something they can take with them once they leave prison.

"It's a blessing," Valdez said of the notebook gift.

Their classroom looks more like an industrial cafeteria than a professional kitchen, but for Thatcher and his students, it's a place to create second chances.

"The program is part business and part culinary. It's practical cooking skills and marketing courses," Thatcher said. "The world is already against them, so I'm here to teach them how to think and problem solve."

Created in 1965 during the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, Pell Grants are awarded to low-income students by the U.S. Department of Education and are used to pay for college. Unlike loans, the grants don't have to be repaid.

Pell Grants were originally available to both incarcerated and non-incarcerated students. That changed in 1994 with the passage of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The new law prohibited people in prison from using federal grants to pay for college.

"Almost all college prison education programs ceased overnight," said Ruth Delaney, director of the Unlocking Potential Initiative at Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit national research and policy organization.

That's because more incarcerated people earn less than a dollar an hour working in prison, Delaney said, and many colleges didn't see the financial benefit. The number of prison education programs dropped from nearly 200 to 12.

Ohio, however, was one of a few exceptions.

Delaney said several colleges in the state worked with the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections to offer advanced job training programs paid for by the state.

"There was a recognition (in Ohio) that college in prison was a valuable experience," Delaney said.

That continued access to higher education put Ohio in "a quite fortunate" position to be part of the Second-Chance Pell Initiative created by the U.S. Department of Education in 2015, said Jennifer Sanders, superintendent of schools at ODRC's Ohio Central School System.

The goal was to determine whether expanding access to financial aid increased incarcerated individuals' participation in postsecondary educational opportunities.

In 2016, 67 colleges in 28 states were invited to participate, including Ohio's Ashland University. The program was successful and expanded each year following, Sanders said, eventually including five of ODRC's seven prison education programs. They include Ashland University, Kent State University, Marion Technical College, Sinclair Community College and North Central State Community College.

A voluntary survey published by Vera in July found that Ohio Second-Chance Pell colleges enrolled at least 4,823 incarcerated students between 2016 and 2022 — the second-highest count after Texas. Incarcerated students took 5,190 credit hours through the Pell program in the 2022 fiscal year, according to ODRC.

Nationally, more than 40,000 students participated in postsecondary education funded through Second Chance Pell between 2016 and 2022, according to Vera.

Now, with the Pell Grant reinstatement, Sanders said two other colleges — Franklin University and Wilmington College — are applying to become prison education programs under the revised initiative. Other colleges have expressed interest as well, she said.

Colleges that apply to offer prison education programs must meet several milestones over the next several years. Those requirements include getting approval from a corrections agency and a higher education accreditor, and completing an application.

Thirty-four states and the federal prison system have their processes in place to begin approving new prison education programs, which cover 1.08 million incarcerated people, Delaney said. But that leaves people in 17 states currently without prison education programs.

Ohio has a leg up on other states when it comes to educating incarcerated students, especially now with Pell Grant reinstatement, she said.

"We're hoping with Pell that more students will engage," Sanders said. "We serve a population that is untapped by many colleges. I hope they see the benefit."

Thatcher certainly has.

He's heard plenty of crude comments over the years as to why he would want to teach incarcerated students. But in his culinary classroom, he said, all he sees are dozens of women a year who are eager to learn.

"I don't care why they're in this class. They want to be in college," Thatcher said.

Thatcher is also quick to snap back with statistics.

More than 18,000 formerly incarcerated people leave prison and return home each year. It costs approximately $30,558 per year to incarcerate one person in a state prison, according to the Health Policy Institute of Ohio. It costs less than $3,000 a year for three semesters to educate incarcerated students, Thatcher said.

"Why would you not want these people to be educated when they leave the facility?" Thatcher said. "We have a whole population who wants and needs to work. They don't want to come back."

Education also helps to reduce recidivism, he said.

Of the several hundred students Thatcher has taught over nine years, only eight have reoffended.

Valdez, who is incarcertated for drug possession and tampering with evidence, said she doesn't plan on being one of them.

After she goes home in January, she wants to find a job in the hospitality industry and one day open up a food truck. She wants to enroll at Sinclair's main campus and finish the degree she started.

"I wouldn't have been able to do it out there because my priorities were all messed up," Valdez said. "I'm grateful I got time to start my college career in here."

Sheridan Hendrix is a higher education reporter for The Columbus Dispatch. Sign up for Extra Credit, her education newsletter, here.

shendrix@dispatch.com

@sheridan120

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: College a possibility for more Ohioans in prison with Pell Grants