As college football evolves, lessons can be learned from NASCAR’s rapid growth, decline

In the crumbling speedways and long-faded echoes of the roars that once gave rise to a national sporting phenomenon, there are now lessons and quiet whispers that a different regional pastime would be wise to heed: There’s a mighty cost in abandoning one’s roots.

There was a time, throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, when NASCAR was considered America’s fastest-growing sport. The likes of Dale Earnhardt and Jeff Gordon became household names in those days, and those in charge might’ve thought the future to be boundless.

And so the businesspeople believed it wise to expand, to take races from places that had given birth to stock car racing, and from people and communities that had nurtured it to civilization from its moonshine-running roots, and move them somewhere else.

Phoenix. New Hampshire. Texas. California. NASCAR, suddenly too big and too corporate for places like North Wilkesboro and Rockingham and Darlington, South Carolina, went national.

It made more money, for a while. More people watched, for a while. The sport grew, for a while. Now, more than 15 years after the most-watched Daytona 500 ever, NASCAR’s premier race comes and goes with much less interest than it used to. More than 19.3 million people tuned into Fox to watch it in 2006, according to sportsmediawatch.com. Fewer than half that many watched it earlier this year.

There are myriad factors in NASCAR’s slow march to irrelevancy, compared to its peak: The drivers became less colorful and more homogenized. Various rules changes eroded the sport’s character. Above all, though, the plight of NASCAR provides a case study for what happens when a regionally-based enterprise forgets where it came from, and what made it special in the first place.

Which brings us to college football.

We’ve now arrived at the time of year that’s come to be known as “Talking Season,” when conferences host their annual media days and when coaches and players give the same answers to the same questions year after year. The ACC’s version begins Wednesday. The Big 12’s was last week. This is a time, usually, of endless optimism, when every offseason move was the right move; when every group of fans has reason to believe that, yes, this will be the year, after all.

At least that’s how it normally is. It is different, now.

‘Seismic shifts are continuing’

About a month and a half before the start of the 2022 college football season, the focus is not so much on anything on the field but instead on everything off of it. It likely would’ve been that way even before the recent revelation that USC and UCLA will leave the Pac-12 for the Big Ten, what with the turmoil surrounding the unregulated free-for-all of name, image and likeness (NIL), and all it has wrought. Yet the latest realignment news has elevated everything to a higher level of chaos.

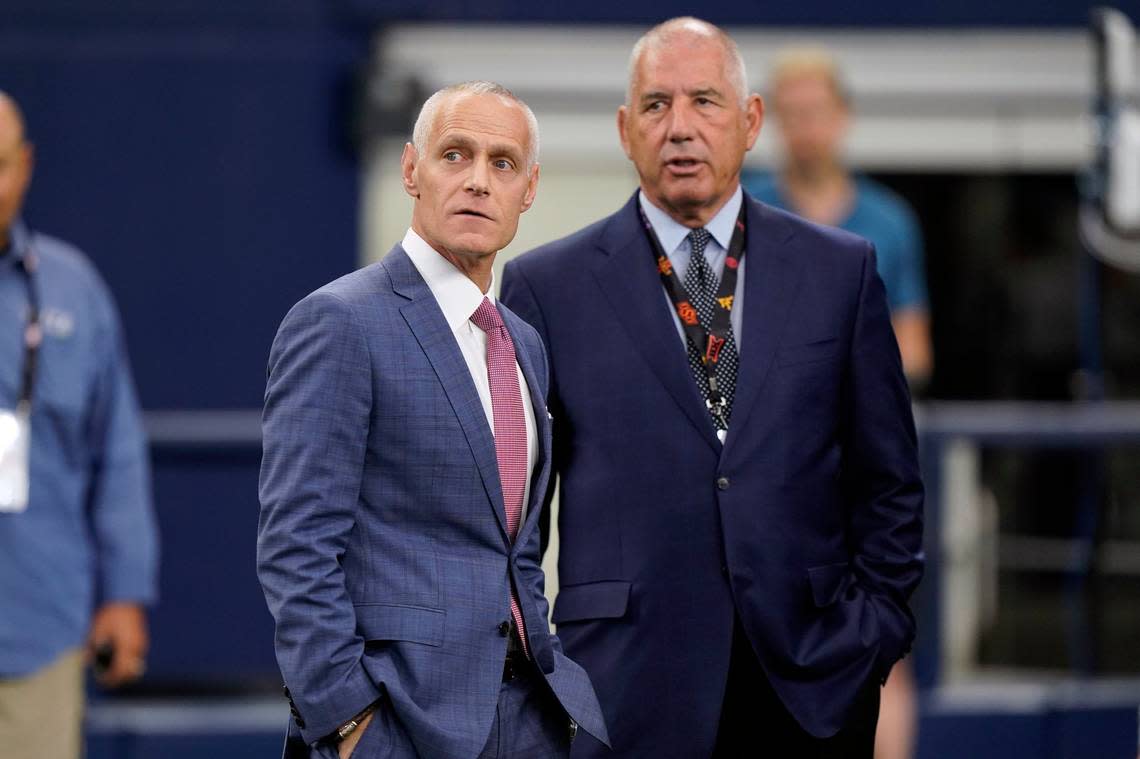

“Indeed the seismic shifts are continuing in collegiate athletics,” Bob Bowlsby, the outgoing Big 12 commissioner, told reporters recently at that conference’s media days, outside of Dallas.

Moments later Bowlsby’s successor, Brett Yormark, restated the obvious.

“Conference composition is once again at the forefront of college athletics,” he said, before pivoting to his top priority when he becomes Big 12 Commissioner on Aug. 1: branding.

“We have an opportunity to grow and build the Big 12 brand and business, be aspirational, define our point of difference,” Yormark said during a corporate jargon-filled address, though one befitting of the current state of college athletics. “Moments like these do not happen often, and we must seize them and make the most of them. It will require incredible work and collaboration.

“One thing is for sure,” he went on, “ there is no doubt the Big 12 is open for business. We will leave no stone unturned to drive value for the conference.”

Under siege?

“Brand” became the word of the day during Yormark’s introduction. Between the questions reporters asked and his answers, the word was mentioned 21 times, and we can expect similar conversations about branding and its significance when the ACC’s media days begin later this week in Charlotte. Jim Phillips, the ACC commissioner, acknowledged in May at the league’s spring meetings that closing the ACC’s revenue gap with the Big Ten and SEC — a problem rooted in part in branding — was at the forefront of his priorities.

Now it feels more urgent. Both the Big Ten (with almost $680 million during the 2020-21 fiscal year) and SEC ($833 million) already generate much more revenue than the ACC ($578 million). That allows those two leagues to give more money to their schools, which allows those schools to spend more on everything from coaching salaries to facilities upgrades to, now, programs oriented to help athletes maximize their NIL earning potential. The financial divide between the Big Ten and SEC and everyone else is about to become even wider, given both conferences will soon have new television rights contracts. The ACC’s deal with ESPN, meanwhile, runs through 2036.

One can forgive the remaining three major conferences for feeling under siege. For not only are the Big Ten and SEC making much more money, but they’re also poaching whomever they want: USC and UCLA from the Pac-12 to the Big Ten in 2024; Texas and Oklahoma from the Big 12 to the SEC in 2024, if not sooner. The moves have caused panic and anxiety for anyone outside of the newly-minted Power Two. Suddenly, schools in the ACC and Big 12 and Pac-12 — and elsewhere — are in the midst of existential crises, wondering if they’ll have a place in the new world order and, if not, the consequences of being left without a seat at the table.

On ‘brand’

In the short-term, college athletics has become one large branding competition. Performance matters, to an extent, and fandom matters, to an extent, but what really matters is a school’s “brand” — its panache, and reach and, maybe most of all, its ability to compel people to tune in and watch their football games, because football TV money drives all. A school’s brand has become the topic du jour on fan message boards, replacing or at least supplementing the evergreen discussions about recruiting and which coordinator should be fired if things don’t improve by Week 3.

In recent weeks, both The Athletic and Sports Illustrated published deep dives related to schools’ brands and understandably so: there’s a reason why the SEC is adding Texas and Oklahoma and not, say, Iowa State and Baylor. The branding breakdowns have included no shortage of analysis of TV ratings, because those ratings provide at least an idea of the perceived value of a given school, or conference. The data distills teams to numbers, the higher the better.

It tells us that, in Week 9 of the 2021 college football season, for instance, 9.3 million people watched the Michigan-Michigan State game at noon on Fox and 7.3 million people watched Penn State-Ohio State at 7:30 on ABC and 6.1 million people watched Georgia-Florida in the Saturday afternoon game on CBS. Study the data for any length of time and soon enough it becomes clear why the Big Ten and SEC are the two wealthiest conferences: their football games usually rate the highest, and by a wide margin.

That same week last season, you’d have to go down eight spots before finding an ACC team in the ratings standings (North Carolina’s game at Notre Dame drew 2.3 million viewers on NBC) and nine spots before a game with two ACC teams (Miami-Florida State, once among college football’s fiercest rivalries, attracted 1.9 million viewers on ESPN). Therein lies part of the ACC’s problem: Its football games don’t attract large enough audiences, at least not compared to its rival leagues.

And yet the ratings and branding conversation, too, underscores the broader crisis threatening college athletics: The entire enterprise risks being data-pointed to death. Locally, there’s a good chance no one knows or cares about how many people watched UNC’s football victories against N.C. State in 2004 or 2012. But if you mention versions of a couple key phrases — “T.A. was in,” or “they punted to Gio” — people will remember the dramatic endings of both games.

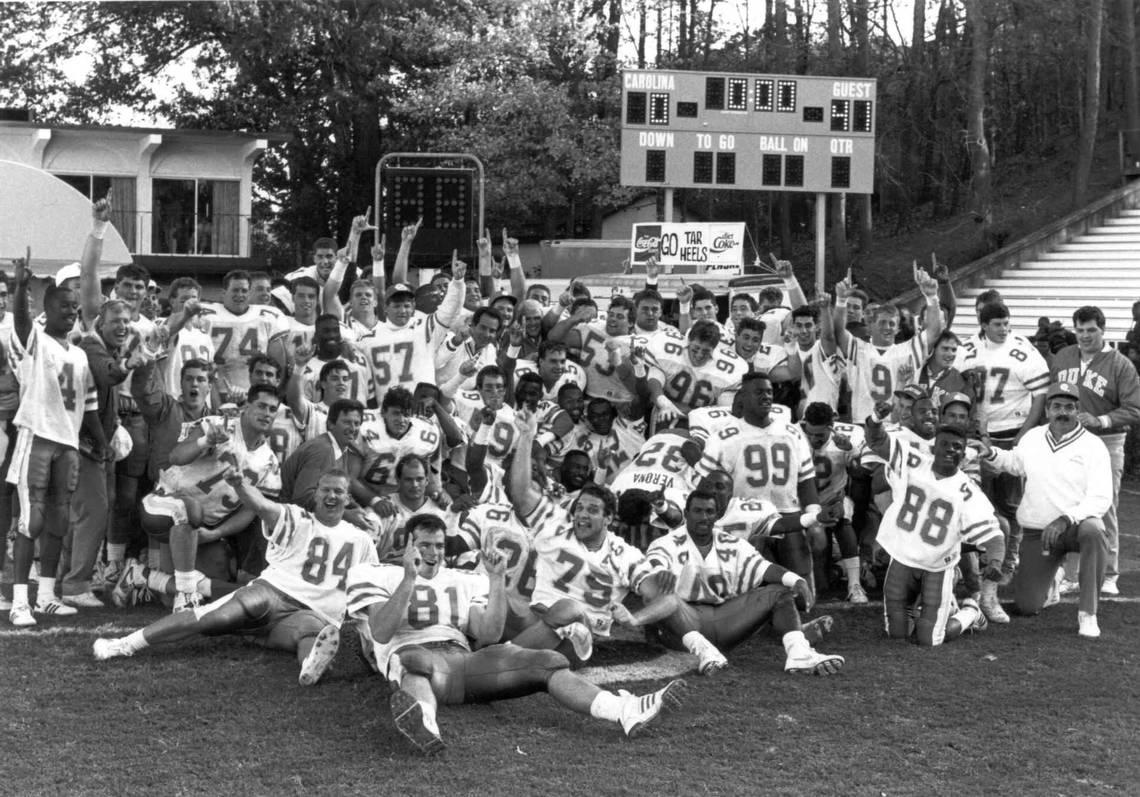

In the same way, Duke’s football victory against UNC in 1989 is not memorable because of its TV viewership but because Steve Spurrier, then the Blue Devils’ head coach, took a picture in front of the scoreboard after his team’s 41-0 victory. Or what about last November, the day after Thanksgiving? N.C. State and UNC fans will remember and talk about the final minute, and the Wolfpack’s improbable comeback, for decades. Was it any less meaningful because it was only the ninth-highest rated game of the week, with an audience of 2.7 million? (Which, by the way, represented the most-watched game for either team in 2021.)

Lacking leadership

That college football finds itself here, with an uncertain future and with a lot of schools scrambling to understand how they fit into it, is representative of a sport that has lacked national leadership and direction for, well — forever. There’s no commissioner to help guide the enterprise through turbulent times. No organizational body looking out for the overall interest of the sport. The ACC, Big Ten and Pac-12 attempted to form an “alliance,” which apparently ended with the Big Ten storming the shores of the Pacific and poaching two of the Pac-12’s most important schools.

Imagine if other billion dollar sports leagues ran themselves the way college football does. It’d be like if the eight divisions in the NFL operated as their own separate entities, without regard for the well being of the larger league. There’d be chaos and turmoil, undoubtedly, when the NFC East raided the NFC North for the Green Bay Packers, who of course would be happy to leave behind their traditional rivals in pursuit of that sweet NFC East TV money.

The strongest part of college football’s “brand,” if it can be called that, has always been its ability to unite communities and regions. Few things, for better or worse, bring a college town together more than a fall Saturday. There’s meaning in rooting on your school, whether you’re an alum or not, and rooting against that other school in the next town or state over.

College football’s “brand” is dependent on where you are or where you grew up. Every conference has its own identity. The culture of the SEC is different from that throughout the Big Ten, which is different than in the ACC and the Big 12 and the Pac-12. Schools still mostly play against teams that are relatively nearby, and the universal truth is that shared geography creates strong bonds and mutual disdain. But now, more and more, the only thing that seems to matter is television money — which conference has the most of it, which schools have access to it.

Lingering questions

College football’s brand is that it’s not the pros. That’s proven to be more and more of an illusion over the years, yes, given the money and the commercialism, but the sport is as popular as it is because of its regional and cultural ties. The nationally-known rivalries, Alabama-Auburn and Michigan-Ohio State and others, might command the largest share of television revenue, but it’s the smaller, regional ones that drive the heart of the sport, and the interest in it. Does that continue if there’s only two conferences that really matter, or do people simply tune out after a while?

Oklahoma and Oklahoma State have played each other 116 times in football. Will Bedlam continue after the Sooners depart for the SEC? USC and Stanford have played each other 100 times. Will that series continue? Nebraska left behind all of its most notable rivals when it joined the Big Ten about a decade ago, and its program, once a national power, is still seeking to recover its lost relevance. Maryland, which long lamented its northern outpost status in the old ACC, is even more of a misfit in the Big Ten. But the checks clear all the same.

Back at the Big 12’s media days last week, Yormark, the incoming commissioner, was talking again about the brand. He was talking about a desire “to become a little bit more national, to position our brand a little younger, hipper, cooler — how do we connect a youth culture, diversify some of the things we’re doing?”

For a moment he sounded a little like a meme-come-to-life, like Steve Buscemi in a backwards hat, toting a skateboard and acting young and saying “How do you do, fellow kids?” in an episode of 30 Rock. In the next beat, Yormark went on and referenced his experience working for NASCAR, where he served as the vice president of corporate sponsorships.

“I’ve been in the brand-building business and the business-building business in my days at NASCAR,” he said, “where we took a sport from predominantly the South and where the roots were and made it a national phenomenon.”

Indeed, NASCAR became a national phenomenon, for a while. Yet as the sport grew, it changed from what had allowed for its success. It abandoned some of the places where it mattered most. It lost part of its soul that it’s still trying to recover. In the process, it provided a lesson for college football, just not the one Yormark recently tried to sell.