They climbed mountains to escape Nazis. Now their great-grandchildren are making the same journey

Over the ridge of the mountain, across the border was the promised land, the neutral territory Spain – an escape, a second chance, a future.

Behind them was Nazi-occupied France and certain incarceration or death.

During World War II, a perilous route through the Pyrenees mountains provided a means for hundreds of thousands of resistance fighters, civilians, Jews, allied soldiers and escaped prisoners of war to evade Nazi pursuers.

For many, the journey up through rocky boulder fields and frozen glaciers was the final stretch in a long and fraught journey across wartime Europe, hiding from German military, Gestapo secret police and SS paramilitary forces.

This month, the route which starts in France’s Ariege Pyrenees, once again echoed to footfalls as 87 people climbed their way from France to Spain, including descendants of those who made their escape, walking to honor their relatives.

The Freedom Trail, whose final ascent is attacked in a zig-zag path through an ice sheet, is an annual “walking memorial,” as Englishman Paul Williams, a mountain guide and guardian of local history, puts it.

Communing with the past

Formally recognized by French presidential decree in 1994 to mark the 50th anniversary of the D-Day Normandy landings that began the liberation of France, the trek remembers those who fled to Spain during the war.

Among previous hikers is Luke Janiszewski, a 25-year-old from the Baltimore area.

“I didn’t have Nazis on my tail, I wasn’t climbing for my life,” he told CNN. But, he adds: “I tried many times to think ‘Wow, my great-grandfather did this with X amount of food,’ and he was driven solely like ‘I need to get into neutral Spain and get back over to England so I can do what I got to do.’”

Lt. Richard Christenson, a B-17 pilot, was shot down over northern France and spirited out over the Pyrenees while the war was still ongoing. But he made it back home to live out the rest of his days with Ruth, his wife.

His daughter Kathryn, 81, who has written a book about his escape, and grandchildren Marie, 52, and Tim, 54, joined great-grandchildren Luke and Jake to walk the train in 2018, its 25th anniversary.

“I’d never even been to Europe,” said Tim, adding that he would never ordinarily have come over just to see the mountains. “But to retrace Grandpa’s steps ‘Oh, in a heartbeat,” he told CNN.

“I felt in a little bit of communion with him, you know?” Luke, who never knew his great-grandfather, remembered.

That reunion with the past came alive over a dinner before the walk, where the Janiszewskis met descendants of the local family who saved Lt. Christenson.

Sitting down with them, Tim reflected on how this human drama played out against the backdrop of America’s role in bringing an end to World War II.

“We came in and saved France but your grandfather or your great-grandfather saved my grandfather as he was trying to help save you. It’s just this beautiful web and connection that makes you feel united in one with everybody.”

Local hero

On the second weekend of July each year, this walk creates its own memories. This year it was dedicated, in particular, to Paul Broué, a French resistance member and one of the founders of the Freedom Trail Association.

Born July 9, 1923, he made his escape over the Pyrenees in July of 1944. Had he not passed away in 2020, this year would have been his 100th birthday.

Broué was the embodiment of local wartime stories – not just the mountain guide “passeurs” but also the families who hid, guided and died to help men like Christenson.

Roughly 50% of British and American escapees came through this area of the mountains, according to Guy Seris, a retired French colonel who is now president of the FTA, which organizes the four-day, 40-mile hike.

Seris is also a local man, from Seix, a town in the lush wooded foothills that is the first stopping point on the trail, and where the local mayor hosts a “vin d’honneur” evening meal to mark the occasion.

“The town and the people of Seix see it as an honor, given the part the commune played during the war,” Seris told CNN.

This year in his speeches to the walkers, he stressed that those old enough, who fought in the war “or lived it or mostly heard it spoken about at home,” had a duty to tell younger generations about it.

It is those memories that walkers carry with them and into Spain. The two countries are bound by the shared life on the mountains – a life of pine forest flocks and herds of belled cows that a border cannot separate.

Before the outbreak of World War II, the region saw the mountain escape routes used in reverse, as Republican refugees crossed into France to flee General Franco’s rule at the end of the Spanish Civil War.

Although Franco was sympathetic to Germany, Spain remained neutral during World War II, largely because of its dependence on US imports. And so, a blind eye was turned to those crossing the Pyrenees.

Escaping Allied servicemen who did make it over would be held in the nearest Spanish town, transferred to a prison camp and freed not long after.

Goosebumps moment

US Air Force Second Lieutenant Frank McNichol was briefly held prisoner in the Spanish town of Isaba when he made the crossing in 1944 after being shot down during a bombing raid.

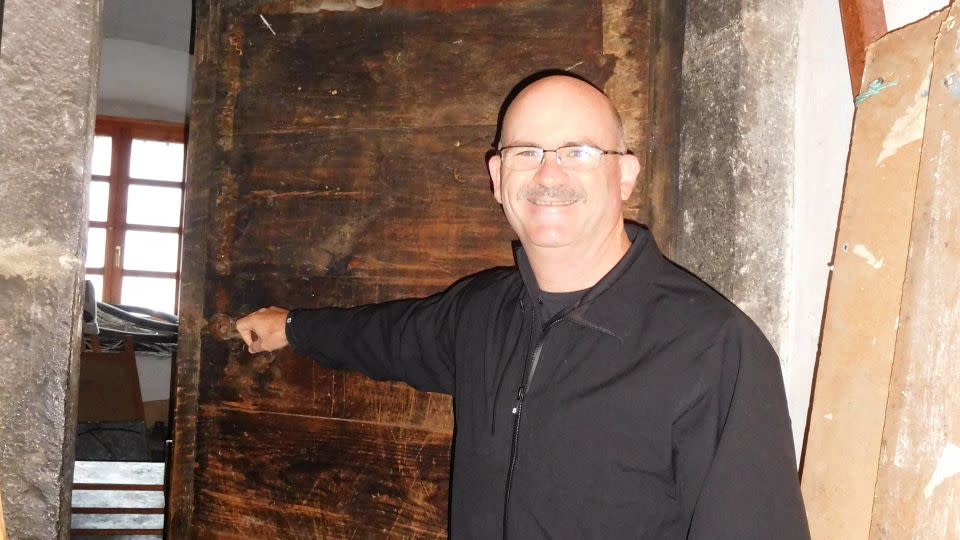

His son, Joseph McNichol, 64, a retired Floridian police officer, recounted making a pilgrimage in 2016 to see the cell where his father had been incarcerated.

“It was a holiday in that part of Spain but our hotel called the mayor, who they knew, and explained the situation,” McNichol said.

“He was more than happy to come that morning and open up city hall and show me the room, which was just a dusty old storage room.”

McNichol said he was only seven when his father later died of liver failure from hepatitis, likely caught from his time in France.

“I never had an adult conversation with my father about anything, not the least of which is this topic.”

Reflecting on seeing the cell in the small town in Spain, having crossed the border 72 years to the day his father was there, he said: “It gives me goosebumps just to talk about it.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com