Climbdown on Russia and the new ‘Belt and Road’: Five key points from India’s G20 summit

India managed to pull off a successful G20 summit without letting Russia’s war in Ukraine undermine the world’s most premier economic forum.

The two days of the summit in Delhi concluded following 200 hours of non-stop negotiations, 300 bilateral meetings between diplomats and 15 draft communiques before reaching a unanimous consensus, said Amitabh Kant, a senior Indian government official leading some of the G20 negotiations.

India’s prime minister Indian Narendra Modi asked the group’s leaders to hold a virtual meeting in November to review progress on policy suggestions and goals announced on the weekend.

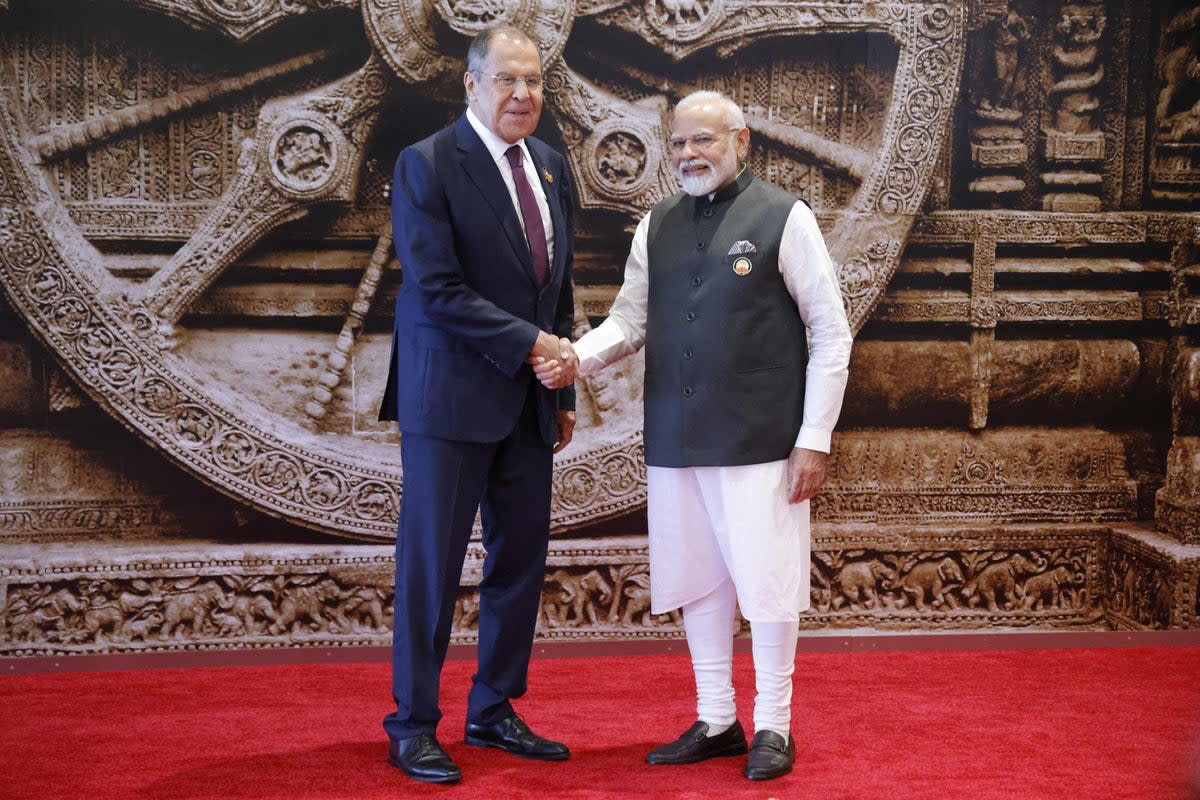

Big win for Russia

The 79-paragraph G20 declaration avoided any direct criticism of Russia for its war against Ukraine – a move described as a significant win for Russia but which was also a failure to condemn the country directly for the invasion.

Russia had objected to the condemnation of what it had called a “special operation” in Ukraine, as Western leaders had pushed for more stern language. The contrasting views had led to an impasse in negotiations as the joint outcome document was worked upon until just a day before the summit began.

The final outcome, an apparent compromise on the language on Russia’s war, irked Ukraine and was much weaker from the Bali Declaration 10 months ago that had called out “aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine”.

The declaration bemoaned the “human suffering” caused by the Ukraine conflict but stopped short of mentioning Russia. “There were different views and assessments of the situation,” the leaders’ statement said.

While the US, UK, and Canada were quick to defend their agreement to the language used, Moscow said it succeeded in preventing the West’s attempts to “Ukrainise” the summit agenda.

Mr Lavrov said the outcome was a “milestone” achievement for long-time ally India and credited it for “preventing attempts to politicise” the G20.

British prime minister Rishi Sunak said the declaration had “strong language, highlighting the impact of the war on food prices and food security” and Canada’s Justin Trudeau said it confirmed Russia’s isolation.

Svetlana Lukash, a Russian negotiator, called India’s G20 as “one of the most difficult G20 summits” in its 25-year-long history. “It took almost 20 days to agree on the declaration before the summit and five days here on the spot,” Ms Lukash told Russian news agency Interfax.

Expansion of G20 with African Union’s expansion

In a success for one of India’s key agendas in the G20, the African Union was accepted as a permanent member of the grouping.

The move strengthened Delhi’s push to amplify the voices of developing nations from the Global South on the world stage. Analysts said it was part of India’s efforts to emerge as a leader of the Global South.

The decision is also a big development for the 1.4 billion people of the African continent who will now have wider representation on the premier economic forum.

Only South Africa from the 55-member bloc was a G20 member until now.

“Honoured to welcome the African Union as a permanent member of the G20 Family. This will strengthen the G20 and also strengthen the voice of the Global South,” Mr Modi said.

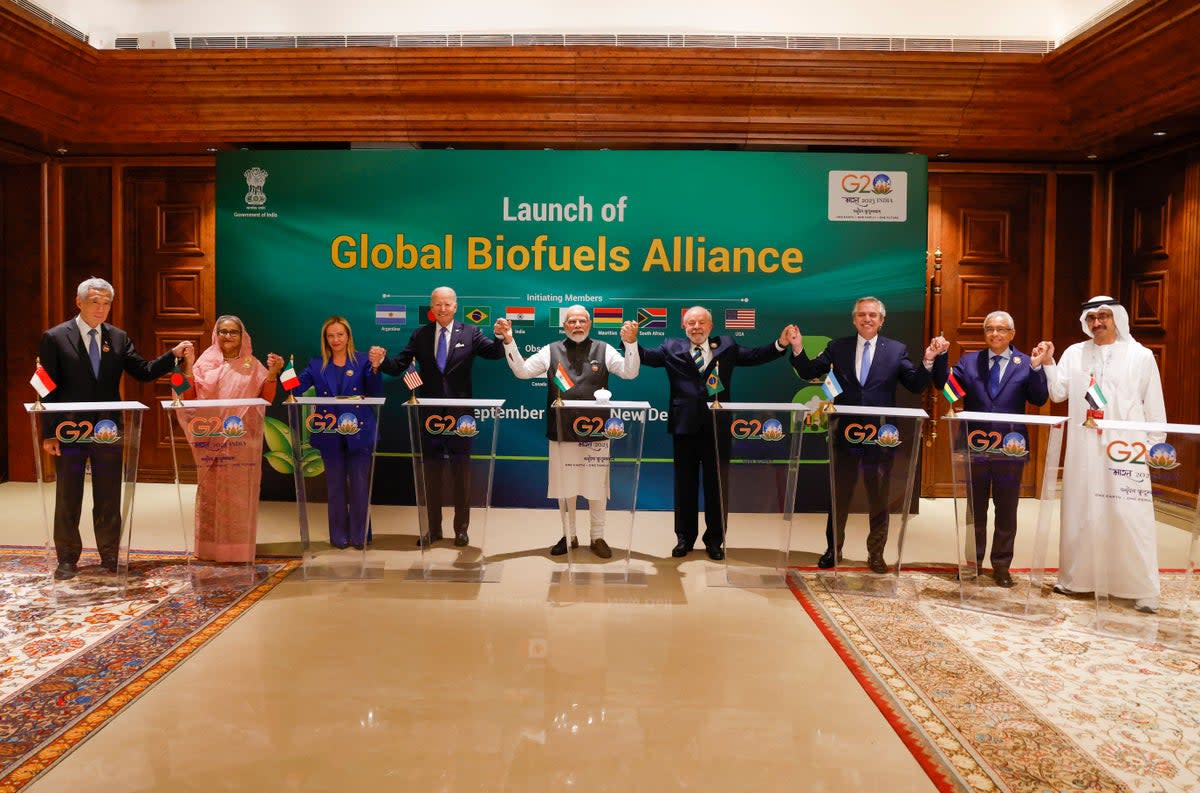

‘Spice route’ corridor to counter China

An ambitious deal that takes along India, the US and Saudi Arabia was worked out on the sidelines of the G20 summit to create what is being called a “spice route”.

The massive project, called the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, will connect Asia and Europe through the Middle East by establishing railways, ports, electricity and data networks, and hydrogen pipelines.

The alliance is seen as an effort to connect a volatile region and counter China’s years-long expansive and global infrastructure projects that are collectively known as the Belt and Road Initiative.

The “spice route” project will be part of the broader initiative called the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment.

The project, for which a timeline has not yet been set, will potentially increase the speed of trade between India and Europe by up to 40 per cent.

The plans are also being seen as a way to foster improved relations between Israel and the Gulf Arab states.

Award winning historian William Dalrymple said the opening of an Indian-Middle Eastern Economic Corridor would revive ancient trade routes up the Red Sea from India to Egypt.

He said it “will again become a global focus of economic and cultural exchange”.

Inclusion of religion in declaration

A paragraph in the G20 declaration that mostly went unnoticed interestingly included a commitment to promote respect for religions.

“...we strongly deplore all acts of religious hatred against persons, as well as those of a symbolic nature without prejudice to domestic legal frameworks, including against religious symbols and holy books,” reads the 78th para of the outcome document.

The addition on religion made a surprise entry.

Officials of the G20 – formed in 1999 after the Asian financial crisis – under India’s presidency have objected to inclusion of geopolitical issues in the economic platform.

Harsh V Pant, vice president of Studies and Foreign Policy at the Observer Research Foundation, told The Independent that the G20 like other platforms is responding to the changing nature of the G20 itself and to make it more relevant.

“When you look at the very character of G20, with the African Union’s entry, one can expect more changes in future declarations and more issues coming up with future declarations.”

The joint statement made a “commitment to promote respect for religious and cultural diversity, dialogue and tolerance”.

The entry comes amid concerns of increasing religious intolerance under Mr Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party and instances of Quran burning in Sweden and Denmark that have sparked protests and discussions.

The Danish government has introduced legislation aimed at prohibiting the public burning of sacred texts.

Climate concerns

The G20 leaders agreed to triple their investments in renewable energy by 2030 and endeavour to augment funding for climate crisis-induced disasters. However, they upheld the existing approach over the phasing out of coal.

Mr Kant described it as “possibly the most robust, proactive, and ambitious document on climate action”.

But many climate and energy experts said it was not as promising even though a powerful message on climate action, especially in light of the rising frequency of natural disasters like extreme heat worldwide, was conveyed by the G20 leaders.

“While the G20’s commitment to renewable energy targets is commendable, it sidesteps the root cause – our global dependency on fossil fuels,” Harjeet Singh, of Climate Action Network International, told The Associated Press.

“Tripling renewable capacity by 2030 is an ambitious, yet achievable goal. Annual capacity additions have more than doubled from 2015 to 2022, rising by about 11 per cent per year on average,” said the International Energy Agency in a recent assessment.

“Just a slightly higher annual growth rate would put renewables on track to meet the 2030 capacity target,” it said.