Chiefs tackle Orlando Brown lives by a promise to his father — but one to himself too

Orlando Brown Jr. is sitting in the basement of his Kansas City home, or his lair, as he calls it, but the first thing that catches your attention is not the 350-pound man who collects a paycheck trying to protect Patrick Mahomes.

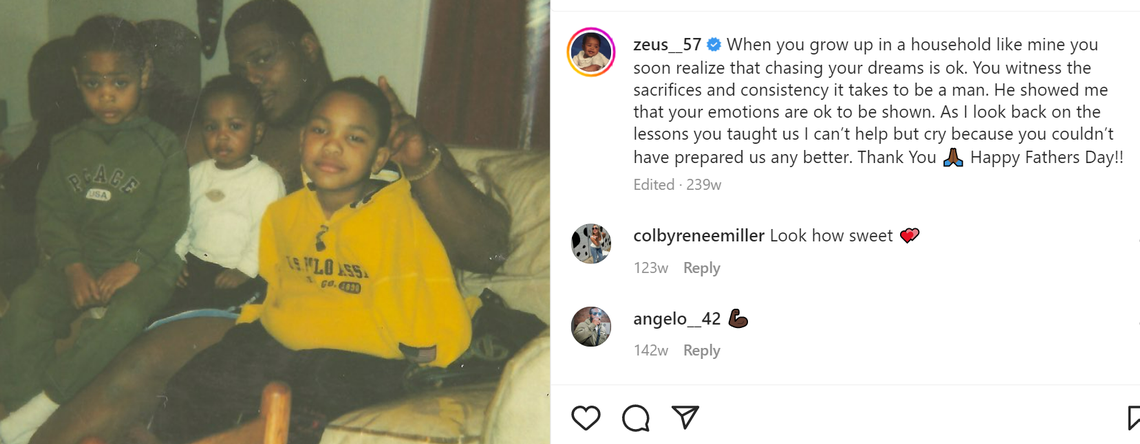

Over his right shoulder, and he points it out in case you miss it, hangs a painting of his father, Orlando Sr., similarly so large that he adopted the nickname Zeus. A local artist gifted the item a couple of years ago, and Brown turned it into the room’s centerpiece. Next, he twists his arm to the left, his index finger detailing a framed, game-worn Baltimore Ravens jersey with his dad’s nameplate stitched on the back.

The items dangle from the walls like intentional conversation pieces, begging for someone to ask about their significance.

And, well, why not bite?

Can you tell me about your relationship with your father?

“I don’t know how long you got,” Brown Jr. says, “because there are a lot of stories when it comes to my dad.”

He ultimately begins with the end, because it has shaped the context of where he sits today — an NFL player like his pops and recently named to his second consecutive Pro Bowl with the Chiefs, who embark on this postseason as the AFC’s No. 1 seed.

That story begins on the morning of Sept. 23, 2011, a date Brown would tattoo on the inside of his left wrist.

His dad had a tradition with his three sons, Orlando Jr. the oldest — or maybe it’s best to classify it as an understanding. Either way, he’d typically go all-out for his kids’ birthdays — call them out of school for lunch or some other planned activity, or perhaps bring the party to them. He once ushered the Ravens mascot to Brown’s classroom as a surprise. Birthdays were a big deal.

And this was one. Brown’s younger brother Justin turned 14 that September day, just one year younger than Orlando, and the two sat in the same classroom at DeMatha Catholic High in Maryland waiting on a call from Dad. What might he have planned?

Eventually, a school administrator popped into their history class.

Finally.

The two brothers tracked the hallway to the principal’s office, but rather than encountering their father there, they were informed their mother was on her way instead. As they sat there, confused, Brown pulled open Twitter on his phone to pass the time.

His brother remembers the next words exactly.

“No way,” Brown said. “This can’t be true.”

Brown handed the phone to his little brother, the Tweet from a stranger still frozen on the phone’s screen:

R.I.P., Zeus.

How the dream started

Orlando Brown Jr. spent part of his childhood traveling the country to watch his dad play football, first with the Ravens, then with the Browns and then back to the Ravens.

As a toddler, his mom says, Brown threw a fit when she flipped cartoons on the TV. He insisted on ESPN. Like most sons, at some point Brown wondered what it might be like to spend his life doing what his old man did, though there was a small problem.

Actually, a very large problem.

Brown was so overweight as a kid that he reached 450 pounds by the eighth grade. That’s not a misprint, though it is the kind of thing you hear and feel it necessary to verify the accuracy.

“I think I would’ve guessed about 500,” says Jammal Brown, a former NFL All-Pro tackle who met Junior when he joined Orlando Sr. for a youth football camp.

The size came from Zeus, who stood 6-foot-7 and weighed 360 pounds himself in his prime and preferred his son focus on his education instead of trying to be like Dad. You might most remember Orlando Sr. as the recipient of an errant penalty flag that pelted his eye and derailed his career, prompting him to shove a referee in retaliation. But at one point, he was the highest-paid right tackle in football, despite having entered the league as a defensive lineman.

He retired in 2005. The machismo outlasted the career.

In middle school, Brown had asked his dad once more to sign him up for football. The response? As long as you play left tackle, and as long as you reach the NFL.

The agreement was made.

At kickoff before his first game, Brown recalls, he looked toward the stands and spotted his father. In the second quarter, he glanced to the same spot.

Gone. His dad had left and driven home.

Second game, same thing. Third game, once more his dad had arrived on time only to leave before halftime.

“I get home, and I’m like, ‘Dad, why do you keep leaving the game?’” Brown says.

And then his voice escalates in volume as he mimics his dad’s response to his question:

“’I can’t watch that soft (junk), man. That (junk) is so soft, man. You’re playing patty cake out there. You won’t finish nobody. Can I get an unnecessary roughness one time?’”

He turned on the TV and popped in a movie.

The Waterboy.

Really.

“I was actually just telling Pat and Travis this story the other day,” Brown says, referring to Mahomes and Kelce.

We’re not talking about Al Pacino’s inspiring locker room speech in Any Given Sunday. Instead, a 1998 comedy starring Adam Sandler as, well, the waterboy who ends up starring on a college football team as a bruising linebacker.

Orlando Sr. cued up a specific scene. Sandler’s character, Bobby Boucher, awaits a snap, and as he looks across the line of scrimmage, he sees players on the other team taunting him by singing, “Water sucks. Water sucks.”

In a fit of rage, the waterboy plows through the offensive line, blocks a kick and returns it for a touchdown.

“And then my dad, he’s like, ‘You see how tapped into this he is? See how Waterboy tapped into this? I need you to be like that when you’re on the football field.’”

Then he left the room.

A mic drop.

With Bobby Boucher as his sidekick.

The next game — “I’m not kidding, the very next game,” Brown says — he lined up against the biggest kid in the league. Well, the second biggest kid in the league, he clarifies.

“And I take the kid, and in my mind, it feels like I’m driving him back downfield for like 20 yards,” Brown says. “It was probably more like three yards or something.”

Wasn’t through with him, either. He stood up, then fell back onto the same defender he’d just pancaked, delivering him something resembling The People’s Elbow. And out of the corner of his eye, he could see his father sprinting down from the top row of the stands.

Oh, crap.

Orlando Sr. opened the gate, charged onto the field and inched closer to his son — then whipped a towel through the air to celebrate what he had just done.

“It’s super funny for me to think about,” Brown says, “but that’s just how he was.”

Suddenly, backed by one sequence, Orlando Sr. started to have the same visions his son had as a toddler.

Maybe he could play in the NFL.

He was right.

But he’d never know it.

A promise. Or two.

A 15-year-old kid stood at a pulpit inside Mount Ennon Baptist Church in Clinton, Maryland. His father’s casket rested beside him.

Within 24 hours of the unexpected death, Brown’s middle brother Justin walked into the high school’s locker room, cleared out every last item in his cubicle and whisked it to the coach’s office.

He was done.

Forever.

“I always wanted to play football because my dad played,” Justin said. “When he passed away, it was too tough, so I played basketball instead.”

At the funeral, a host of former NFL players were among those in attendance. A speech from then-Browns coach Bill Belichick was read aloud; in it, he referred to Zeus as one of his all-time favorite players to coach.

When a teenage kid followed, he issued a promise that would guide the next decade of his life.

What could have signaled the end of his football career — what was the ending of his brother’s football career — represented something else entirely for him.

A beginning.

“My dad told me to stick with what you start,” Brown said that day, as his mom, Mira, recalled. “And I’m not going to give up on this.”

Orlando Sr. had seen his son play left tackle only a handful of times — you’ll recall that was the requirement for allowing him to sign up for football — and he had never watched him play varsity football.

His death, at age 40, came suddenly. He was found in his Baltimore apartment. A medical examiner would rule the cause to be diabetic ketoacidosis. The examiner further stated that there was no evidence he had even treated his diabetes.

He didn’t, because he didn’t know he had it. Brown said his father had self-diagnosed himself with the flu, and he refused to seek medical treatment.

Instead, he drank orange juice.

“My dad was real big on anti-medicine and not seeing the doctor,” Brown says. “I haven’t really spoken out about that part, but that’s obviously one of the reasons why I do what I do.”

Since being traded to the Chiefs in April 2021, Brown has made multiple trips to Children’s Mercy hospital in Kansas City. During his most recent stop, he donated $50,000 to their Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet research program.

In ensuing TV hits, he often refers to his father. But he has rarely mentioned the additional layer — the full reason he’s there.

“So many people in the Black community think like my dad did,” Brown says. “And we have to change that.”

Black men are twice as likely to die from diabetes as white males, according to the U.S. Department of Health. They are 36% less likely to adhere to diabetic medications, even in situations with equal access to them, per the National Library of Medicine.

Brown doesn’t need the statistics. He has personal evidence. Both of his paternal grandparents also died from complications from diabetes. His brother Justin was diagnosed as a Type 1 diabetic at age 7.

After his father succumbed to the disease, Brown’s life took on a different purpose.

Guided by one pledge he made to his father.

And one he subconsciously made to himself.

On to the NFL

Hours after his dad’s death, on the afternoon of Sept. 23, 2011, Brown walked into the bedroom where he surmised his dad had taken his last breath. He initially stood at the entryway, scanning the room.

Before leaving, he grabbed a few items from the floor and the closet, including a bandanna his dad often wore atop his head.

Days later, at the funeral, Brown would vow to watch over his siblings — two younger brothers and two younger half-sisters — but he was a grown man in stature only. His mother would move her three sons to Atlanta. As the new kid in class, not exactly physically able to blend in with a crowd, he needed his own guidance. His own help.

Back in Baltimore, Jammal Brown had heard about Orlando Sr.’s death and felt a nudge to place a phone call. Years earlier, while in high school, Jammal lost his mom to lupus, and a school counselor helped raise him.

“Someone was there for me,” Jammal says, “And I just had this feeling from the Most High that I should be that guy in Orlando’s life.”

Brown turned to a new mentor.

And he turned to family.

And he turned to football.

The latter returned the least stability. He “rode the bench” as a sophomore at Peachtree Ridge in Atlanta, and after initially winning the starting job his junior season, that disappeared after he was responsible for two sacks and three holding penalties in one half. To this day, Brown calls himself the most unathletic player in the NFL, a description that irks his position coach, Andy Heck.

For six years, he had been confronted with a mountain of evidence that football might not be his career path, but he didn’t have it in him to quit.

“The emotional stress and the emptiness of losing a parent — it’s so hard for me to put into words, because we had such a great relationship,” Brown says. “Where I was in my life, I had so many questions long-term, and I felt like he had so many answers. How am I going to get to the NFL? How am I going to get to college? Like, I’m not even starting in high school.

“Losing him, (football) became my emotional outlet. I had made a commitment to him, and I was at peace with that.”

He kept tangible reminders along the ride. In high school and later at the University of Oklahoma, Brown donned the same bandanna his father once wore. He’s bought several replicas since, and though the NFL doesn’t allow their specific type to be worn during games, you will typically see some inside his locker in Kansas City. Heck, he’s even adopted the same nickname as his father — Zeus — and uses the moniker on his social media pages.

He has spent the last 11 years trying to emulate his father.

But trying to ensure no one else does.

Every few months, Brown re-lives the hardest moment of his life, the moment he calls “rock bottom,” and he does it voluntarily. Over and over again. He will spend as much time as you have talking about diabetes. That’s how this story, the one you’re reading now, came to be.

It’s not that his dad had the disease.

It’s that he didn’t know of it. It’s that he refused to even find out.

From afar, Orlando Brown Jr. is a story of a kid who followed his dad’s path to NFL stardom. Up close, though, his life has included one marked and intentional detour. And he’s standing at the outset of his own path, waving for others to follow.

“I haven’t necessarily dove into it with other people, but that’s one of the reasons I do the TrialNet stuff,” Brown says. “This could’ve helped him be here.”

In November, Brown was named the NFL Players Association’s Community MVP of the week after his most recent trip to Children’s Mercy. He stopped by after a Chiefs practice one afternoon and presented the $50,000 check. He has made lasting relationships here since arriving in KC two years ago. Doctors know him by name, and him by theirs.

His long-term future in this city is uncertain — he is playing the 2022 season on the NFL’s franchise tag, amounting to an expensive one-year contract that will begin anew his free agency in March.

He cried the night this NFL journey began, when he was selected in the third round of the 2018 draft. He’d fallen in the draft after a poor performance at the Scouting Combine. See, unathletic, he’ll say. But the call finally came, and when it showed a Baltimore phone number, he knew. He would be wearing the same uniform his dad once wore. The same uniform that sits in his basement today.

Three years later, he demanded a trade elsewhere. His time in Baltimore had provided him flashbacks to some of his most cherished memories — walking into the team practice facility, his dad telling him he’d one day do the same. How could he forget that?

His dad was right about that, too.

But Brown wanted to play left tackle, and with the Ravens, he was stuck on the right side. He had been called selfish on his way out of town for demanding a trade rather than sticking with what best suited a perennial playoff team. But he was just going to have to live with the fact some would never understand.

He’d made someone a promise.