Chapel Hill residents question council motives, plan to change single-family zoning

Chapel Hill council members heard Wednesday night from residents worried about investors turning single-family homes into rentals and young adults struggling with the high cost of being town residents.

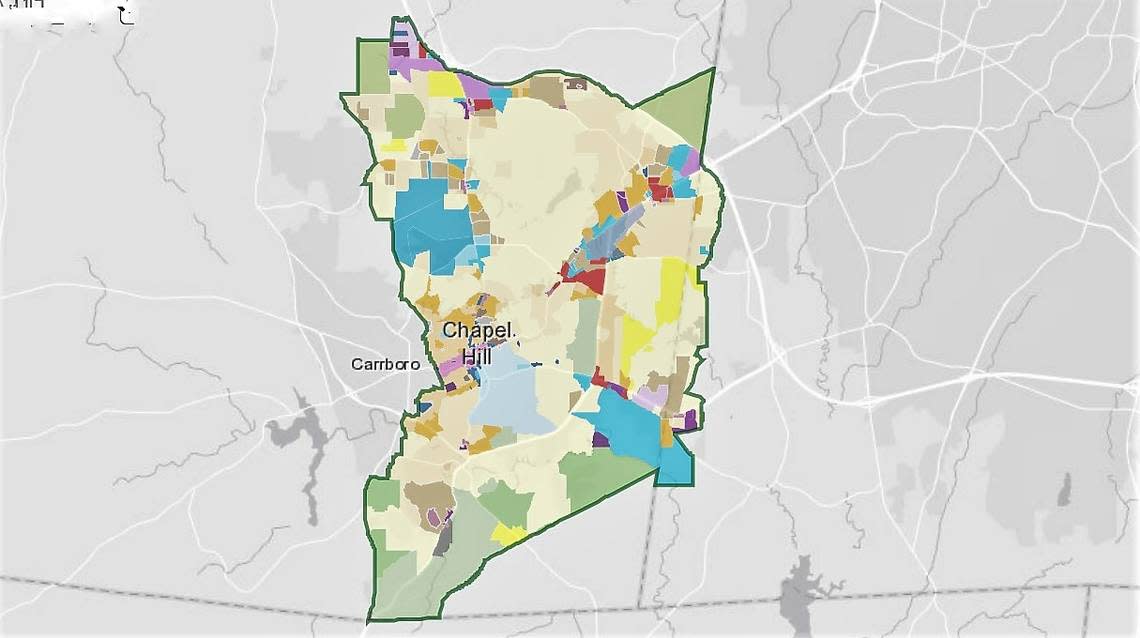

The town held a public hearing on proposed changes to “upzone” some of Chapel Hill’s 247 single-family neighborhoods, but not those with a restrictive covenant or homeowners association. The future of nine neighborhoods with a Neighborhood Conservation District is still in question.

Upzoning modifies or eliminates single-family zoning in favor of more housing diversity. It is rooted in the idea that more options will make it easier for more people, especially young families, older adults and lower-income workers, to live where they work.

That’s important in Chapel Hill, where 43,349 people drove into the town for work in 2019, according to U.S. Census data. Another 14,697 residents who lived in Chapel Hill left the town for work, while over 6,400 lived and worked in Chapel Hill.

The council voted at the end of a long night of discussion to continue the public hearing to Feb. 22. Community information sessions will be held virtually on Jan. 31 and in person on Feb. 2.

“While we as a community are looking for ways to increase our missing middle, more inclusive housing and more affordable housing, this is one option to consider,” Mayor Pam Hemminger said. “We do not yet have enough information to implement this change. We’ll need to learn more. Other cities have implemented this approach, and we’re looking at their results as well.”

Housing needs, proposed changes

The council started working on the new policy in 2021, with four council members asking town staff to research ways to spark more construction of “missing middle” housing, such as townhomes, duplexes and cottages.

Business Street consultant Rod Stevens was hired and has worked with Canadian urban planner Jennifer Keesmaat, on a Complete Community policy framework for creating walkable, diverse and affordable neighborhoods.

The proposed land-use changes would let property owners build up to four apartments on lots currently zoned for single-family homes, or cottage courts with up to a dozen units surrounding a central courtyard.

Most other design limits, such as height, lot size, setbacks and limits on impervious surfaces, such as driveways, would apply. Projects with three or more units also would have to address stormwater and tree canopy issues, and projects with six or more for-sale units would have to meet the town’s inclusionary zoning ordinance, which requires 15% affordable housing.

That would not be the case if a developer subdivides the property before applying for a construction permit, town staff said.

The changes would not help the town add affordable housing or prevent student rentals, staff said. It also would not dictate whether housing is for sale or lease. They don’t expect much change at first, based on experiences in other towns, staff said.

“We’ll be interested in seeing the effects, but by encouraging smaller units and more yield out of land, it would create opportunities to deliver housing in a more affordable manner and broaden the price points,” planning manager Corey Liles said.

Zoning reform, investment, fears

Significant public and private investment is attracting thousands of new residents to North Carolina.

Durham approved zoning changes near its downtown in 2019, allowing townhouses, cottages and small apartments next to single-family homes in residential neighborhoods. Raleigh also approved zoning changes recently after years of planning and public debates.

The trend is now galvanizing Chapel Hill neighbors, many of whom fear the construction of luxury apartments next door, the slow rise in already hefty property tax bills, and gentrification.

Multiple speakers, including those who supported the changes, urged the council to step back and spend time considering potential outcomes.

“This zoning, as we have already heard, it will not lead to affordable housing. I don’t think it will lead to workforce housing,” resident David Adams said. “What it will lead to is corporatization of housing. This is an invitation for developers to come in, buy up property and put up rental housing at rental rates.”

He urged the council to table the discussion until after the November 2023 municipal election.

Others, including Greenwood neighbor Arturo Morosoff, said it shouldn’t take more than a couple of months to help the public better understand the plan and determine who could be affected. Greenwood is covered by a Neighborhood Conservation District.

“I think people are envisioning large apartment complexes in the neighborhoods; that’s definitely a fear out there,” Morosoff said. “There’s also sometimes a concern about the safeguards, like, what if this moves too fast and questions about whether blanket zoning is really the answer, or are we just allowing developers to shape the future of Chapel Hill.”

Students, young adults pushed out

Abigail Welford-Small, a Westwood resident and young working professional looking “to stay in town and start a family,” said the changes that people fear are already happening.

“This town is mostly becoming college students and older folks, many of whom have argued and complained about these potential changes, but if it continues in this direction, there’s not going to be a town,” Welford-Small said. “It’s going to be old retirees and college kids, and people like me won’t be able to live here.”

UNC students also weighed in, rejecting claims they are a neighborhood problem. Students “just need a safe, comfortable place that we can afford,” said UNC senior Simon Palmore, but settling down in Chapel Hill “seems unattainable” now.

“Speaking for myself and people like me, we have a lot to offer this community. We want to stay here. We want to serve the town, and what we really need is for the town to give us the ability to do so,” Palmore said.

Council member Tai Huynh also defended renters, noting they “contribute to our community just as much as any homeowner.”

“At the core of what we are trying to do, it’s not housing affordability. This is about housing justice,” Huynh said. “Our community is finally beginning to acknowledge the discriminatory roots of single-family zoning, not only in our community, but across this entire nation … and we need to reckon with that past. This is about having more neighbors, more opportunity.”

Acknowledging, reversing historical trends

Experts say zoning changes won’t create affordable housing in the short term and not without other changes.

Zoning started over 100 years ago as a way to promote more homes for working-class families, according to Alexander von Hoffman, a senior research fellow and lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

The policy soon became a tool of racism and exclusion wielded by white homeowners, government officials and developers who wanted to keep out Black and immigrant, working-class families, Hoffman wrote in a 2021 blog post.

In the 1970s, towns added more rules, ostensibly to protect the environment and prevent sprawl, he said, followed by the proliferation of development fees, advisory board reviews, and lengthy approval processes that increased the cost of building homes.

Unless those barriers to development are addressed, upzoning in single-family neighborhoods is unlikely to create affordable housing in the short term, said Emily Hamilton, a research fellow and director of the Urbanity Project at George Mason University.

Westwood neighbors who live near UNC’s campus already see family homes being replaced with townhomes, along with parking problems and speeding, Anna Creissen said.

“Our family and many of my neighbors are concerned that the town’s recent focus on density and affordability has unleashed a development frenzy that will contribute to historic neighborhoods like ours disappearing,” Creissen said.

In contrast, the historically African-American Northside neighborhood near downtown is reversing the effects of investors who replaced family homes with larger student rentals, leading to work on a Neighborhood Conservation District and housing preservation programs.

Northside is the town’s “lodestar,” Elkin Hill resident Fred Stang said.

“When you create an opening for developers to come in, it might start as a dribble, but there is going to be a building boom at some point,” Stang said. “Do you really have the safeguards in place to create the kind of community we really want to create? I’m not sure this proposal, as it currently stands, does that.”

Distrust, council motives questioned

The conversation Wednesday also reflected online allegations that council members will benefit from the change without having to deal with the implications.

The News & Observer found that three council members — Mayor Pro Tem Karen Stegman, Camille Berry and Michael Parker — live in neighborhoods where the changes could be allowed. Berry lives in an Erwin Road apartment, and Stegman lives in Booker Creek.

Parker lives in the Greenbridge Condominiums on Rosemary Street, which is in a Town Center-2 district. However, staff told the council in an email that the proposal could allow townhouses in the downtown district.

Stegman said she takes offense at questions about which council members would be affected, because that’s not how they make decisions. She urged residents to contact town staff and council members with their concerns, instead of turning to social media.

“I do not view this as something we would be inflicting on a neighborhood. I view it as a way to create or continue to build diversified neighborhoods,” Stegman said. “That is the goal, and I think this is a small but important step as one of many tools in this strategy that this council has been working on for many years now.”

Hemminger and other council members — Adam Searing, Amy Ryan and Huynh — live in neighborhoods governed by homeowner associations. Council members Paris Miller-Foushee and Jessica Anderson live in neighborhoods with an Neighborhood Conservation District zoning.

Mller-Foushee also countered the narrative that she would not be affected because she lives in Northside. The neighborhood has an NCD, but it also allows duplexes, triplexes and affordable housing, she said, calling some emails she received disappointing.

“I really appreciate community members who are expressing their concerns and even their opposition to the proposals that we are looking at, but there are also emails that are full of fear mongering, bigotry and right-down dog-whistling racism,” Miller-Foushee said.

Raleigh residents also have expressed distrust in their city council following recent changes to allow more duplexes, townhomes and small apartment buildings in single-family districts. The changes also allow construction of more tiny homes and backyard cottages.

The N&O reported that residents in one of Raleigh’s wealthiest neighborhoods have galvanized against a plan to tear down a 100-year-old home and replace it with 17 townhouses priced at roughly $2 million each.

The fears are not unfounded, some experts say, although few studies have been done.

The Orange Report

Calling Chapel Hill, Carrboro and Hillsborough readers! Check out The Orange Report, a free weekly digest of some of the top stories for and about Orange County published in The News & Observer and The Herald-Sun. Get your newsletter delivered straight to your inbox every Thursday at 11 a.m. featuring links to stories by our local journalists. Sign up for our newsletter here. For even more Orange-focused news and conversation, join our Facebook group "Chapel Hill Carrboro Chat."