Chapel Hill needs more housing. Public hearing Wednesday on single-family zoning changes

Note to print readers: Today’s newspaper went to press before Wednesday night’s public hearing. Please see a report from the meeting later this week.

Significant public and private investment is attracting thousands of new residents to North Carolina, sending housing prices and leasing rates through the roof and forcing many longtime residents to leave the Triangle in search of affordability.

Elected officials and their staffs are searching for novel solutions, including zoning changes so developers and property owners can build townhouses, cottages and small apartments next to single-family homes in residential neighborhoods.

Durham approved such changes near its downtown in 2019; Raleigh recently approved zoning changes after years of planning and public debates and is holding five workshops for residents and builders through Feb. 23.

The trend is now galvanizing Chapel Hill neighbors, many of whom fear the construction of luxury apartments next door, the slow rise in already hefty property tax bills, and gentrification. Others hope the changes will bring more “missing middle” options and see it as a long game to get affordable housing.

On Wednesday, Chapel Hill’s Town Council will hold a public hearing on the proposal to “upzone” multiple neighborhoods. Town staff is still working to determine which neighborhoods would be affected if the change is approved.

The council’s meeting begins at 7 p.m. at Town Hall on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. It will be followed by two community information sessions. One event will be held virtually Jan. 31. The other will be held in person on Feb. 2.

The council could continue the discussion to Feb. 22, when a vote is possible.

Upzoning, which modifies or eliminates single-family zoning in favor of more housing diversity, is rooted in the idea that more options will make it easier for more people, especially young families, older adults and lower-income workers, to live where they work.

That’s important in Chapel Hill, where 43,349 people drove into the town for work in 2019, according to U.S. Census data.

Another 14,697 residents who lived in Chapel Hill left the town for work, while over 6,400 lived and worked in Chapel Hill.

Land-use changes proposed

Chapel Hill’s proposed changes have been in the works for a few years. In September 2021, council members Karen Stegman, Tai Huynh, Michael Parker and Allen Buansi, who is now a state House member, asked staff to study the issue and bring back ideas.

The town hired a consultant, Rod Stevens with Business Street, to review current housing and needs, and most recently, started working with Canadian urban planner Jennifer Keesmaat on a new Complete Community framework aimed at creating walkable, diverse and affordable neighborhoods.

Wednesday’s hearing will put several changes on the table, including a plan to let property owners build up to four housing units on lots currently zoned for single-family homes.

Other changes would:

▪ Eliminate density limits in all zoning districts and set minimum lot sizes, maximum floor area ratios, setbacks, building height, and limits on driveways and other impervious surfaces.

▪ Set minimum and maximum parking rates.

▪ Allow residential property owners to build triplexes, fourplexes and cottage courts, featuring three to 12 small houses clustered around a central courtyard. Triplexes and fourplexes are only permitted now in higher-density zones that also allow apartments.

▪ Create specific design standards and subdivision rules for townhouse projects with five or more units.

▪ Establish a zoning compliance permit process that only requires staff approval.

Will this create affordable housing?

Not alone, and not in the short term, experts say.

Zoning started over 100 years ago as a way to promote more homes for working-class families, according to Alexander von Hoffman, a senior research fellow and lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

The policy soon became a tool of racism and exclusion wielded by white homeowners, government officials and developers who wanted to keep out Black and immigrant, working-class families, Hoffman wrote in a 2021 blog post.

In the 1970s, towns began adding more rules, ostensibly to protect the environment and prevent sprawl, he said, followed by the proliferation of development fees, advisory board reviews, and lengthy approval processes that increased the cost of building homes.

Unless those barriers to development are also addressed, upzoning in single-family neighborhoods is unlikely to create affordable housing in the short term, said Emily Hamilton, a research fellow and director of the Urbanity Project at George Mason University.

HOAs, conservation districts different rules

The proposed policy would not change land-use rules in neighborhoods that are governed by a homeowner’s association or that are in one of the town’s Neighborhood Conservation Districts.

Council members could ask staff to research changes to the town’s NCD guidelines that would expand the variety of housing options.

Homeowner’s associations, which are subject to state law, have more expansive powers to regulate the character and appearance of a neighborhood.

Would council members be affected?

Only three council members — Stegman, Camille Berry and Michael Parker — live in neighborhoods where the policy change would allow more types of housing. Berry lives in an apartment on Erwin Road; Stegman lives in the Booker Creek neghborhood; and Parker lives in the Greenbridge Condominiums on Rosemary Street.

Mayor Pam Hemminger and council members Adam Searing, Amy Ryan and Huynh live in neighborhoods with homeowner’s associations that would not be subject to the new housing rules.

Council members Paris Miller-Foushee and Jessica Anderson live in neighborhoods covered by a Neighborhood Conservation District overlay zoning, which could be modified in the future.

How much housing is needed?

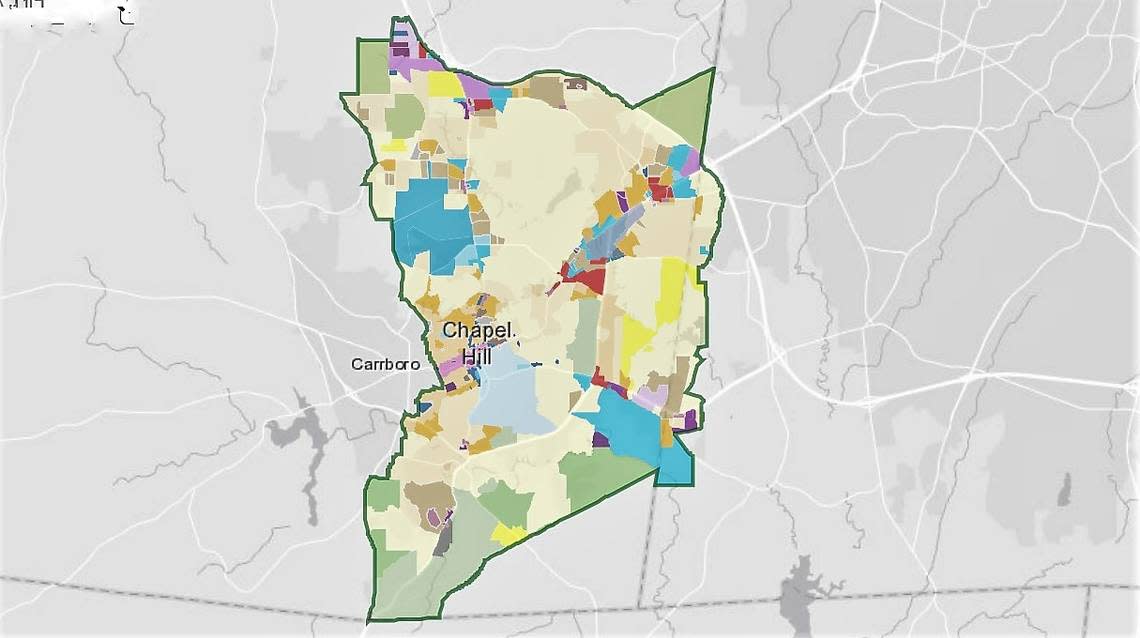

Zoning maps show single-family neighborhoods cover much of Chapel Hill’s available land, leading to an “inefficient use of the land” and higher housing costs, town staff said. About 75% of the housing in Chapel Hill is not affordable to households earning less than 80% of the area median income, they said.

That’s $53,500 for a single person and $76,400 for a family of four, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, making even rental housing unaffordable to the lowest-paid workers and leaving many professionals, including police, firefighters, teachers and nurses, to navigate traffic jams and longer commutes to neighborhoods in nearby counties.

Chapel Hill isn’t growing as fast as other towns either, according to U.S. Census data that showed the town adding just 3,895 people between 2010 and 2021 — an average growth rate of 0.62% a year.

That was slower than the average annual growth rate for Carrboro (0.8%), Orange County (1%) and Hillsborough (4.2%), as well as the state of North Carolina (0.9%).

UNC-Chapel Hill, which along with its related entities own roughly 30% of the town’s land, reported a 1.2% average annual increase in its undergraduate enrollment during that period, and 0.8% average annual increase in its graduate and professional students.

U.S. Census estimates from 2010 and 2021 showed the town only increased its housing stock by a couple of hundred units in that time.

The town now needs more than 5,000 affordable homes, whether for sale or lease, to serve its low-income residents, town staff and housing advocates have said.

In his 2021 report, Stevens recommended a 35% increase in housing production. That would add about 485 homes a year, only 10% of which should serve UNC students, Stevens said.

Gentrification, higher taxes drive fears

A number of Chapel Hill residents have urged the council to slow down, citing the experience of other cities and towns that have eliminated or scaled back single-family zoning districts.

They argue upzoning could encourage gentrification, let developers replace existing homes with more expensive rentals, and leave lower-income homeowners with unaffordable property tax bills.

In Raleigh, recent changes to allow more duplexes, townhomes and small apartment buildings in former single-family districts, have some residents saying city leaders have lost trust with the public. The changes also allow the construction of tiny homes and backyard cottages in more areas.

The News & Observer reported that residents in one of Raleigh’s wealthiest neighborhoods have galvanized against a plan to tear down a 100-year-old home and replace it with 17 townhouses priced at roughly $2 million each.

The fears are not unfounded, some experts say, although few studies have been done.

One oft-cited study of changes in New York City found that upzoning between 2002 and 2009 led to neighborhoods becoming whiter, with more speculative development and higher property values. Another, more recent study examined zoning changes in Chicago and found rising property values but very little new housing being built.

Daniel Herriges, editor-in-chief for the nonprofit advocacy group Strong Towns, argued in a Jan. 19 report that those studies have been taken out of context. The Chicago study, for instance, only looked at a small area of the city served by transit, he said.

Developers are only going to replace homes with multifamily housing if they have interested buyers and can make a profit, Herriges said, and most towns don’t have the population growth to fill all those new units.

“This is a story well chronicled in many cities,” Herriges wrote. “The one hot neighborhood with a conspicuous flock of construction cranes, fueling the widespread perception of a development boom even though most residents live in neighborhoods untouched by it.”

The story was updated at 10:11 a.m. Jan. 25, 2023.

The Orange Report

Calling Chapel Hill, Carrboro and Hillsborough readers! Check out The Orange Report, a free weekly digest of some of the top stories for and about Orange County published in The News & Observer and The Herald-Sun. Get your newsletter delivered straight to your inbox every Thursday at 11 a.m. featuring links to stories by our local journalists. Sign up for our newsletter here. For even more Orange-focused news and conversation, join our Facebook group "Chapel Hill Carrboro Chat."