CEMEX gravel mine near Fresno allowed to skirt environmental laws. Here’s how | Opinion

The gravel mine where a multinational building materials company wants to blast a 600-foot-deep pit along the San Joaquin River north of Fresno has been allowed to operate without environmental reports mandated since Richard Nixon occupied the Oval Office.

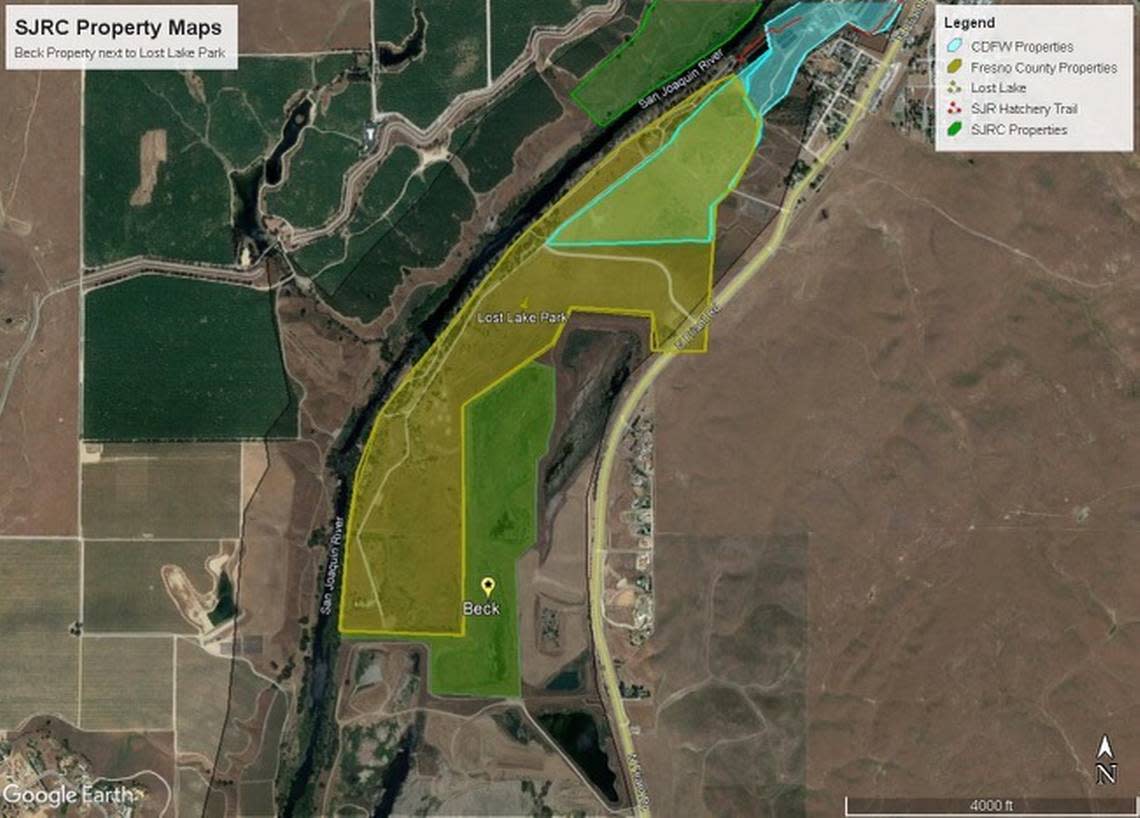

More concisely, the Rockfield quarry south of Lost Lake Park (where CEMEX and others have mined aggregate deposits for about a century) lacks a dedicated Environmental Impact Report. Such a document does not appear to exist.

Fresno County would probably take issue with me over these statements. In a Feb. 14 letter notifying government agencies and stakeholders about CEMEX’s application to extend mining permits set to expire in July, county planners refer to an “existing EIR” that will be “utilized for the current proposal” unless issues are raised that trigger the California Environmental Quality Act.

However, when pressed for the “existing EIR” in official inquiries, they provide environmental reports prepared in the 1980s for CEMEX’s processing plant (located 2 miles south of the quarry on Friant Road) and for a neighboring property the company doesn’t own and hasn’t recently been mined. Beck Ranch was purchased by the state for the San Joaquin River Parkway.

Nonetheless, those are the two relevant EIRs furnished by county officials in emails and linked on the planning department’s website.

Opinion

“It’s pretty wild to me that this mining operation was allowed for so many decades without environmental documents,” said Sharon Weaver, executive director of the San Joaquin River Parkway and Conservation Trust, who raised the issue in a letter of response to Fresno County planners regarding CEMEX’s permit extension application.

“I don’t know of any mine that has operated on this river, or the Kings River for that matter, that does not have an EIR as of today.”

Why isn’t there a specific EIR for this particular gravel quarry? The most concise explanation can be found on page 4 of a Supplemental Draft EIR written in 1987 that covers both the Lone Star processing plant (named after the company that used to own the operation) and Beck Ranch.

After allowing that “issues have been raised” over the “little environmental work” performed at the 350-acre excavation site, the report’s authors state the company’s 1960-issued “original permit predated CEQA requirements and the 1985 approval of (an operating permit to mine an additional 147 acres) did not require an EIR.”

In common parlance, the quarry was grandfathered in before state and federal environmental laws took effect in 1970. Each time the company mining that site sought to extend or amend operating agreements, the county went along without requiring a cumbersome environmental review. Giving itself license to sidestep federally listed species like the California tiger salamander and the impacts of substantial residential development whose drivers also use Friant Road.

County: ‘Existing EIR is adequate’

County planners failed to mention the “predated CEQA” detail in 2004 while recommending approval to revise the mine operator’s conditional use permit to allow for a 20% increase in daily truck trips to meet the building boom. (That permit was issued to RMC Pacific Materials, which CEMEX acquired in 2005.)

Rather, they wrote “an EIR was prepared for these projects and the Board (of Supervisors) considered and certified the EIR in compliance with CEQA.” Then went on to rationalize their decision that “the existing EIR is adequate for the project.”

When, in fact, any EIR that scrutinizes the environmental and ecological impacts of the quarry owned by CEMEX appears nonexistent. That location “predated CEQA requirements,” remember? The only EIRs for that gravel operation are more than 35 years old, and pertain to the company’s processing plant 2 miles away and for 106 acres of state-owned land adjacent to Lost Lake Park.

“The county continues to give off the impression there’s an existing EIR that covers the quarry,” said Joseph Penbera, a Friant resident and former dean of the Craig School of Business at Fresno State. “That’s simply not true.”

These concerns are being raised now because CEMEX’s mining permits along the San Joaquin River expire in three months — before a draft EIR for the company’s audacious blast mine proposal will evidently be submitted.

Because even in Fresno County, industries can’t get away with dynamiting to 600-foot depths along California’s second-longest river (in proximity to a federally operated dam, an increasing number of homeowners and a state-sponsored river parkway effort) without first providing environmental documents mandated by state and federal law. Prepared by the same consulting firm they employed in the 1980s.

I first reported about the blast mine in January 2020, one month after CEMEX submitted initial plans to the county. A public hearing was held, via Zoom, in June. Three years later, there’s still no EIR for public consumption. Nor even a progress report.

With the clock ticking on its existing permits, CEMEX now seeks a four-year extension to continue mining until 2027. Ample time for the company to cue up the blast mine proposal, which is its real aim.

‘They’re doing this in the dark’

I say that because aggregate reserves (at least those mined by traditional methods) along the San Joaquin are greatly depleted. CEMEX’s quarry at 14765 N. Friant Road, bordering Lost Lake Park about a mile south of the town of Friant, should’ve been tapped out years ago.

In the 1987 Supplemental EIR referenced above, it was estimated that the “resource” would be completely excavated from the existing quarry and Beck Ranch by 2002. In a 2007 Bee news story about the industry shift to mining gravel along the Kings River, environmental consultant John Buada is quoted saying the San Joaquin “is down to its last few tons” of gravel.

Well, here we are in 2023. With CEMEX seeking a four-year extension of expiring permits to continue mining a quarry that has never undergone an EIR. Simply to give consultants more time to prepare a new EIR that tries to justify methods more destructive than the river has ever seen.

If enough folks and agencies don’t step up forcefully to oppose what’s happening, the county will continue to go along.

“They’re doing this all in the dark and we need to shed some light,” said Penbera, who lives in a gated neighborhood across Friant Road from the quarry. “People just feel like they’re powerless in situations like this, and the reason they feel powerless is because the deals have already been made before the public gets involved.”

Besides Penbera and the nonprofit Parkway Trust, the city of Fresno also submitted initial comments to county planners regarding CEMEX’s application. A letter signed by city planning director Jennifer Clark said the county’s 36-year-old traffic study failed to account for significantly increased vehicular traffic on Friant Road or consider pedestrian and cycling use near Woodward Park, where there have been multiple recent fatalities.

“The City has determined that the existing EIR is no longer adequate for the proposed project because substantial changes have occurred with respect to the circumstances under which the project is undertaken,” Clark wrote. “These changes will require major revisions of the previous EIR.”

A previous EIR that, as it turns out, doesn’t even cover the quarry where CEMEX wants to continue mining.