What the Carolinas can expect as Danielle, other tropical weather swirl in the Atlantic

It’s been said time and again — the last two months of hurricane season have been unusually quiet. It begs the question:

Is there a storm slumbering above the ocean that could soon wreak havoc?

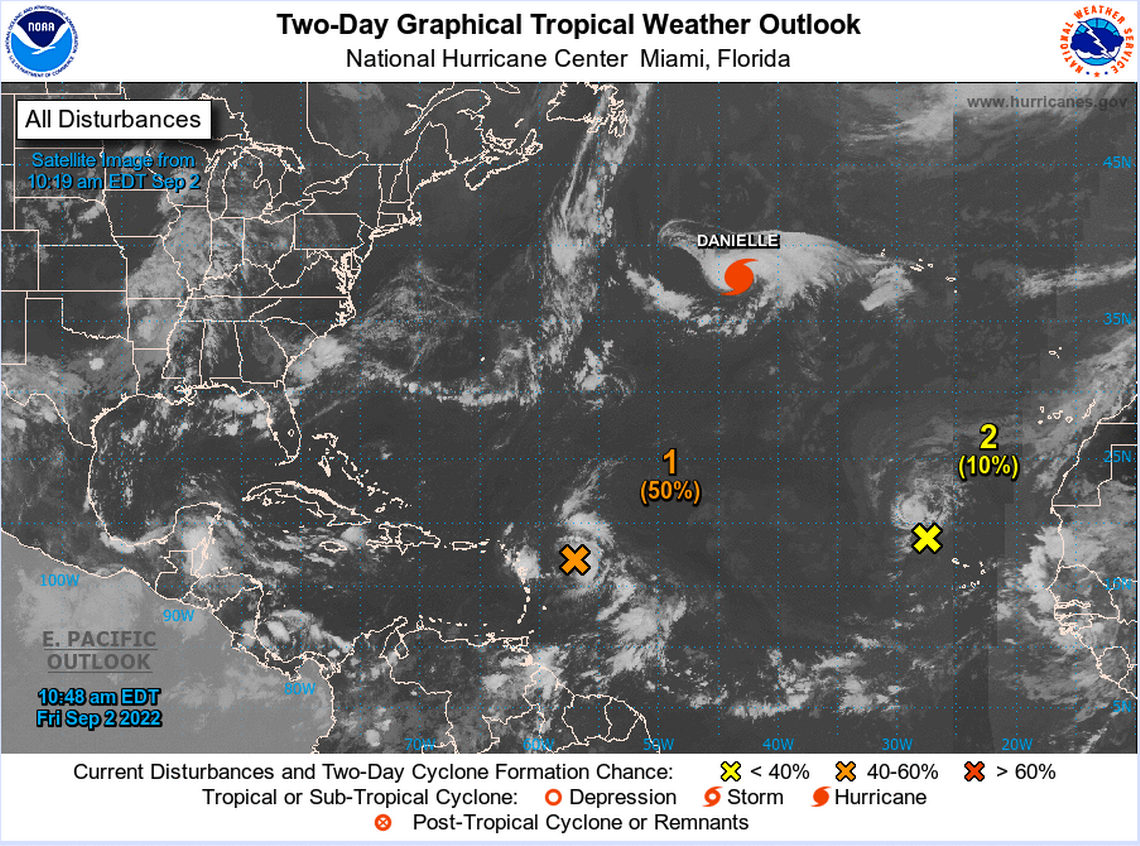

Tropical Storm Danielle formed in the Atlantic on Thursday and was upgraded to hurricane status on Friday morning. Danielle is the first named storm since Tropical Storm Colin snuck up on the Carolinas on July 2.

It’s possible, though, Danielle might never reach shore and instead just hover out in the Atlantic and ultimately fade away.

Danielle isn’t the only weather system that poses a risk as hurricane season reaches its traditional peak over the next two weeks. There are several other weather systems floating about in the Atlantic that could strengthen in the coming days, though none of them has made a particular case for doing so.

Broken records

This year was only the third time since 1950 when there was not a single named storm during the month of August, according to the National Weather Service.

And it wasn’t until Friday morning that Tropical Storm Danielle became Hurricane Danielle, marking a full two months from when Tropical Storm Colin formed to when the first hurricane of the season finally formed.

Danielle formed rather quickly, National Weather Service meteorologist Steve Pfaff noted, but the storm might not make landfall anywhere. Right now, the storm is kind of tracing a bit of a loop, floating in the Atlantic but not really going in any particular direction that could lead it to causing significant problems.

The main risk posed by could be swells and rip currents along the coast of the Carolinas around Labor Day and the days following. That’s what happened last year with Hurricane Larry, a long-lived storm that killed seven people, including one man who drowned in a rip current off of a South Carolina beach. Larry formed at the exact same time as Danielle, becoming a Tropical Storm on Sept. 1 and a hurricane on Sept. 2.

Looking back, there were four other similarly quiet periods in past hurricane seasons.

1992: Seven named storms

2006: 10 named storms

2009: Nine named storms

2014: Eight named storms

The first three of those years happened during El Niño years, which typically portend below-average hurricane seasons, and 2014 was a neutral season.

Right now, forecasters believe the Atlantic Basin is in the middle of a La Niña, which is associated with more active seasons, though studies after the season ends could downgrade that to a neutral status like 2014 if current low-level activity continues.

Why so quiet?

Two main factors have contributed to the quiet hurricane season so far.

The biggest one is a stronger-than-usual Saharan air layer floating over the Atlantic, Pfaff said. Basically, what has been happening is really dry air and dust from the Sahara Desert in Africa blew west over the Atlantic and has hovered there for much of this summer.

This inhibits tropical weather from forming because those storms need a lot of moisture. Dry air, in effect, kills any storms that do try to form.

“The dust from the Sahara Desert blows thousands of miles across the Atlantic basin, and you get extremely dry air,” Pfaff said. “That extremely dry air is a limiting factor, and that really was entrenched across a good chunk of the Atlantic basin.”

The other issue has been wind shear. The jet stream has been stronger than usual this summer, ripping up tropical storms as they start to coalesce.

“That’s something that the tropical storms and hurricanes do not like, is stronger winds, even though it’s a ironic — they produce strong winds,” said Stephen Kebbler, a forecaster in the National Weather Service’s Wilmington office. “But for the development and strengthening of the storms, they don’t like strong winds.”

There also just haven’t been that many tropical waves forming off the coast of Africa, Pfaff said, which is where a lot of the weather systems that ultimately end up in the Carolinas begin.

Staying wary

The peak of hurricane season is still about a week away — Sept. 10.

Even if we pass Sept. 10 without any major events, there’s still a chance a big storm could develop later in the season, Pfaff said.

All it takes is one big storm to do a lot of damage. In 1992, the year with just seven named storms, Hurricane Andrew devastated the Bahamas, Florida and Louisiana.

Andrew was a Category 5 storm and was one of the most destructive hurricanes to ever hit Florida. The storm left 65 people dead and caused $27 billion in damage ($57 billion in today’s dollars).

Hurricane Hazel, one of the most destructive storms to ever hit the Grand Strand, made landfall on Oct. 15, 1954, as a Category 4 hurricane.

“We don’t want to send (people) down the wrong road because it’s been as quiet as it is,” Pfaff said. “We need to maintain that vigilance in all of our communities through October.”

The final issue to keep in mind is remnants of tropical storms and hurricanes. Last year, remnants from Hurricane Fred, a storm that made landfall in the Gulf Coast, floated up through the Florida Panhandle through Georgia and to the mountains of western North Carolina. And when the storm reached North Carolina, it dumped rain on the mountains, produced tornadoes and caused severe flooding that resulted in millions of dollars in damage and endangered the lives of the people in that region.

“That’s another issue we deal with — people think it has to be a direct landfall,” Pfaff said, “but that’s not the case.”