ByGone Muncie: Police Matron Alfaretta Hart’s 1914 battle for 'Cocaine Alley'

On Jan. 9, 1914, Muncie police raided the city’s near southside brothels, gambling dens and illegal saloons. At the time, this red-light district east of Walnut and south of the tracks was known as "Cocaine Alley."

Muncie police arrested about 40 people, including 25 prostitutes and a dozen speakeasy and cathouse patrons.

Muncie’s new mayor, Rollin Havilla "Doc" Bunch, orchestrated the blitz to fulfill a campaign promise to abate the Magic City’s houses of ill-repute. The Evening Press reported, “(T)he new administration has announced that it will pursue a determined effort to ‘clean up’ Muncie.”

The city in the early 1910s was known as a "wide-open" town — a euphemism for a community that tolerated a level of early 20th century vice — gambling, drugs, liquor and prostitution. Sufferance for each was hotly debated in the years before World War I. Places like Muncie were ground zero for progressives pursuing societal reform.

In those days, organized gambling was illegal but generally ignored when hidden and made outright invisible with a bribe. Hard drugs like cocaine and heroin were available in Muncie in the early 1910s but widely condemned. Reformers’ concerns about both were addiction and its impact on families.

Likewise for alcohol.

Beginning in the 1890s, temperance reformers pushed Delaware County’s local governments to pass ordinances banning the sale of spirits.

They met fierce opposition.

Local "wets" advocated for legal saloons and regulated liquor sales, while "drys" generally sought total prohibition. When and where booze was suppressed by law, speakeasies, known then as "blind tigers" or "blind pigs," opened in Muncie.

The city’s sex industry also flourished in this generation.

Stories about "houses of ill-fame" appeared frequently in local newspapers between the mid-1880s and World War I.

Cops raided and arrested often but rarely forced closure.

Sex workers typically just paid a fine after a night in jail and returned to ply their trade. Many local reformers actively opposed prostitution outright on moral grounds and abhorred the associated trafficking.

All these issues came front and center in the 1913 mayoral race.

Munsonians that autumn had a choice of five candidates, all of whom postured against vice.

The Republicans nominated local industrialist Michael Broderick, and Democrats ran physician and city councilman Rollin Bunch. They faced off against the Progressive Party’s Harry Kitselman, socialist Carl Johnson, and grocer George Wilson, the Citizen’s Party candidate.

Wilson and Kitselman were the most vocal about Muncie’s dens of iniquity. Kitselman, the son of a local steel wire baron and rollerskate tycoon, remarked during his campaign that “if I am elected mayor of Muncie, I will exterminate the blind tiger business and the houses of ill-fame.”

Bunch, a known wet on the liquor issue, offered voters a measured platform, promising “all ordinances in the city of Muncie shall be enforced as well as the laws of the state.” He also pledged to hire a "police matron" — a female officer assigned to cases involving women.

For years, Munsonian reformers had called on the Muncie Police Department to hire a woman. A leading advocate for such was Daisy Barr, a Quaker preacher and reformist goody-goody about town.

“Muncie also needs a police matron,” the Rev. Barr told a Morning Star reporter in June of 1913. “Girls are being ruined not by twos or threes but by dozens.”

Bunch won the election by a plurality of votes.

Within a week, a delegation led by Barr and local doctors Lucius Ball and Edward Mason, met with the mayor-elect to formally advocate for a police matron.

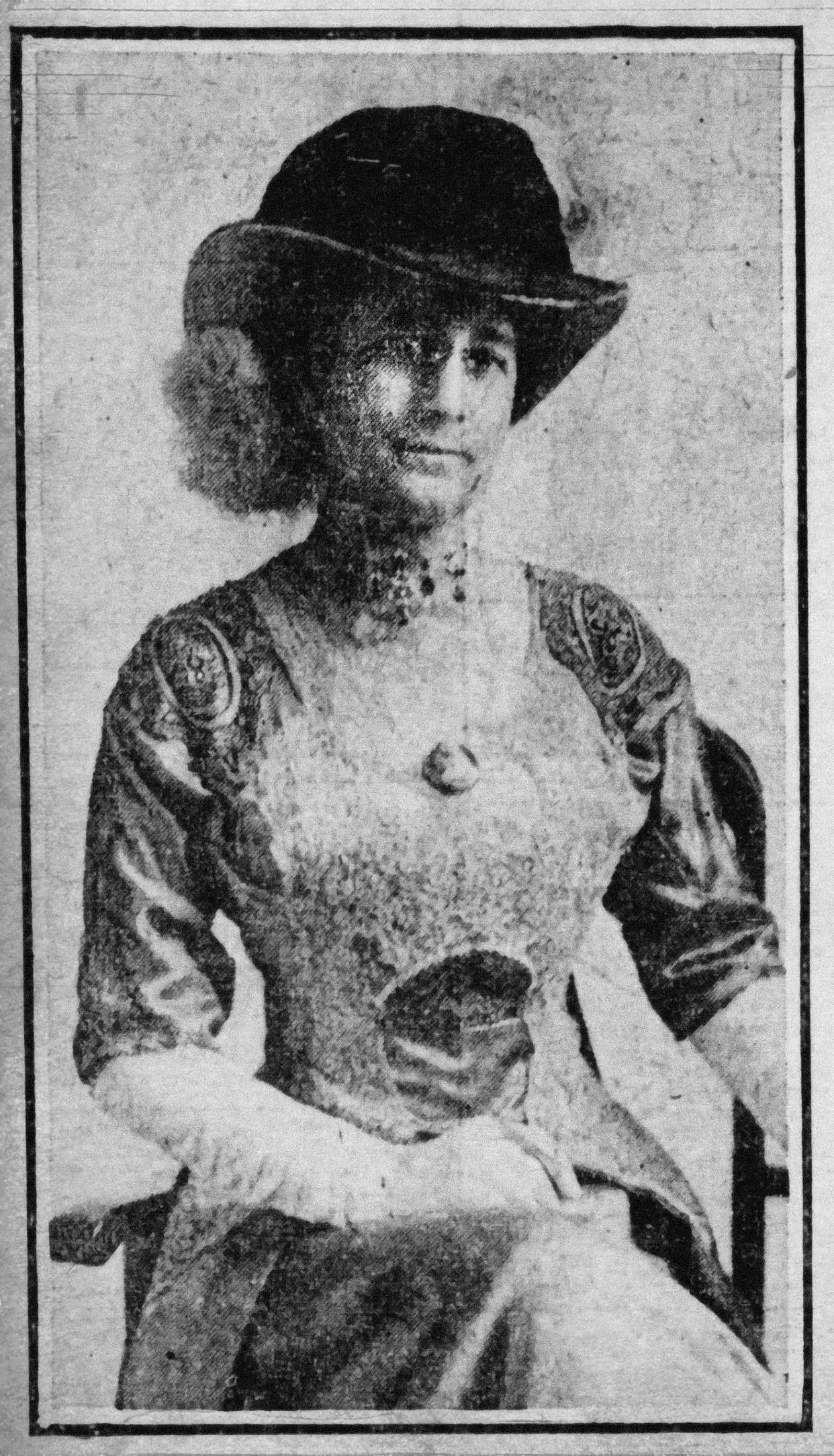

A few days later, Bunch announced Alfaretta Hart for the role.

The Star praised the decision in an editorial, writing: “Mrs. Hart has long been known as an ardent and eloquent advocate of the uplift and purifications of the morals of the city.”

Alfaretta Martha (Poorman) Hart was indeed well known by Munsonians as a reformer in 1914, as well as a member of high society.

Her husband, Thomas, was a prominent gas-boom-era industrialist and co-founder of several companies, including Maring-Hart Glass and Inter-State Auto. The millionaire couple frequently rubbed shoulders with fellow Munsonian patricians, but, unlike most of their Protestant peers, the Harts were Roman Catholic and attended St. Lawrence.

Alfaretta was born in 1861 to Christian and Martha Poorman. Her father was a prominent Ohio businessman, publisher and state politician. The Poormans hailed from Bellaire on the Ohio, just downriver from Wheeling, West Virginia. In 1883, Alfaretta married Thomas Hart, a second-generation Irish-American and local glassmaker. They moved to Muncie five years later during the boom and launched Hart Glass Manufacturing in Dunkirk and Maring-Hart Glass Co. in Boyceton on Muncie’s northeast end.

We know a fair amount about Hart’s reformist views from archived newspapers.

From the early 1890s through 1914, local press published several of her speeches, op-eds and letters.

They ranged from flag-waving praise of the U.S. during the Spanish-American War, to ardent defenses of Catholicism.

She wrote scathing attacks on Clyde Fitch’s risque 1884 play, “Sapho,” and Elsie Clews Parsons’ 1906 book, “The Family.” When the Ohio legislature attempted to pass laws regulating women’s dress in 1913, Hart deplored their hypocrisy: “Men wishing to become famous through the introduction of reformatory laws, should first begin on the male sex.”

Hart advocated that religion, not civil law, was the best tool to police morality.

She wrote in March 1913: “We can never reach the moral sense by legislation.” She later told a reporter, “It is utterly useless to send drunkards and prostitutes to jail.” Incarceration did nothing to lessen demand.

Alfaretta was an ideal choice to serve as Bunch’s police matron. She harbored socially conservative progressive views, but was a wet on temperance, advocating for regulated sale. To underscore her anti-prohibition bona fides, she even spoke publicly against drys at Wysor Grand on the eve of a temperance referendum in 1914.

During her 11-month tenure as police matron, Hart investigated or fielded cases of runaways, assault, rape, and prostitution. She handled 40 cases in her first month alone, operating from a suite of offices in the Johnson Building. Two weeks into the job, Hart led a raid on a blind pig in Cocaine Alley.

But as the year progressed, Alfaretta’s unabashed Catholicism and vocal anti-prohibitionism brought enemies.

One of them was Daisy Barr, who, later in the 1920s, would resurface in Indy as an Imperial Empress of the Ku Klux Klan. Hart might have been pressured to resign; she did so officially in November of 1914 citing ill health.

Alfaretta and Thomas eventually moved to Texas and bought a furniture store. In her later years, Alfaretta wrote for the Dallas Journal. After her death in 1951, Muncie’s police matron came home and was buried at Beech Grove Cemetery.

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a Senior Lecturer of Media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Journal & Courier: Muncie police Matron Alfaretta Hart’s 1914 battle for 'Cocaine Alley'