Would you buy a soda with a dying foot on the label? UNC researchers want to find out.

The UNC Mini Mart, a corner shop a couple miles from main campus, resembled a real store in almost every way.

The shelves were stocked to the brim with name-brand snacks, soft muzak played over the loudspeakers, and a cashier accepted cash at the check-out.

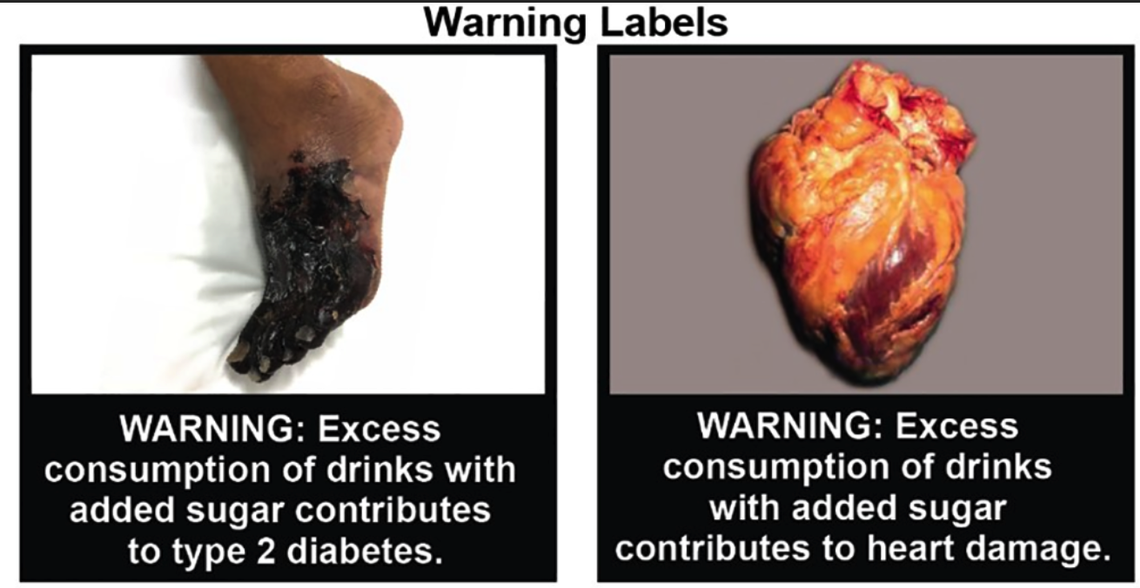

The one critical difference came inside the drink refrigerator. Drinks with added sugar — like Fanta, Coke and Gatorade — had a warning label:

“WARNING: Excess consumption of drinks with added sugar contributes to type 2 diabetes.”

Above it, a photo of a gangrenous foot, dying from the toes up.

Researchers have long understood the power of packaging.

In Australia, scientists spent months finding the least appealing cigarette pack color to reduce smoking (they ultimately landed on a murky brown-green).

Shortly after Chile added nutrition warnings to packages of sugary drinks, purchases of those beverages dropped 24%.

Several meta-analyses, the gold-standard of scientific evidence, and clinical trials have shown that front-of-package labels help consumers avoid unhealthy food and stop smoking.

The UNC Mini Mart — a scientific lab made to look uncannily like a real store — allows researchers to empirically test how labels and store placement impact how people buy food.

This research is particularly important now, as the Food and Drug Administration works on creating new regulations that could mandate front-of-package labels.

“A funny, scrappy experience”

Typically, when researchers study food packaging, they sit participants in front of a computer, show them photos of different packages, and ask them which product they would theoretically buy.

The problem with this type of study is that what people say they will buy and what they actually buy aren’t always the same.

Marissa Hall and Lindsey Smith Taillie, both researchers at the UNC Gillings School of Public Health, set out to design an experiment that would ask participants to pay real money for products they could take home to eat or drink.

“It allows us to actually test what these policies would look like in the real world,” Smith Taillie said.

The realistic store would also let them conduct randomized studies in a store setting, a rare study design in nutrition research, Smith Taillie said. For example, they could randomly assign their participants to two different groups: one that sees normal sodas in the mock-store, and one that sees bottles with images of a diseased heart.

This type of randomization would be difficult through partnerships with retailers, who might be hesitant to put warning labels on their products.

The first challenge was finding funding for their mock-store.

“The NIH is not going to want to spend their money on creating a lab,” she said.

So, Hall and Smith Taillie pooled together extra funding and scoured liquidation sales to build the store on a “shoe string budget.”

The pair found their central food shelf at a nearby Sears’ out-of-business sale. They bought a second-hand commercial refrigerator from a gas station owner, which they hauled back to UNC in the back of a family truck.

“It was a pretty funny, scrappy experience,” Smith Taillie said.

Next, they had to figure out whether a lab-store hybrid needed a dairy license (it did not) or to pay sales taxes to North Carolina (it did).

After their 250-square-foot mini-mart was finally up and running, they found their efforts had paid off — 94% of participants they surveyed said the lab felt like a real store.

Maybe more importantly, they found that purchases at the UNC Mini Mart were in line with what participants bought at real grocery stores, which they evaluated by collecting grocery receipts for a week.

Hall and Smith Taillie began designing studies for the store.

A tool to fight diet-related diseases

One of the first studies the two researchers designed centered around whether graphic warnings would dissuade parents from getting their children drinks with added sugar.

They asked more than 300 parents to pick out a drink for their child from the shelves of the UNC Mini Mart.

For half of the participants, the sugary drinks were put out with normal labels. The other half of participants saw the same bottles with a warning label that depicted a gangrenous foot or a diseased heart, both potential long-term health consequences of excessively consuming sugary drinks.

They allowed the kids to tag along during the food-shopping, to mimic real-life shopping even more.

“You’re making these split second decisions about what to buy and half the time you have a kid pulling on your sleeve asking you to get the sugary cereal,” Hall said.

Hall and Smith Taillie found that the graphic warning was effective at dissuading parents from purchasing the drinks with added sugar. Just 28% of parents in the warning label group purchased sugary drinks, compared to 45% of parents in the other group.

Furthermore, they found the warning label was effective regardless of the participant’s race, income or education level.

Hall said it’s still not exactly clear why this packaging works — whether it’s introducing consumers to new information about the health risks of sugary drinks or whether it’s just bringing those risks to the top of their mind.

She said she thinks it could be a combination of both.

Either way, she said these front-of-package warning labels could be a valuable tool to combat diet-related diseases, like type 2 diabetes, which are on the rise in the United States. It’s a tool that other countries have already successfully adopted, she said.

“You’re giving people information exactly when they need it — when they’re making a decision in a store,” Hall said.

Teddy Rosenbluth covers science and health care for The News & Observer in a position funded by Duke Health and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work.