Broken Promises: How long must Miami wait for a park at Heat arena? 26 years and counting | Opinion

Twenty-six years, and we’re still waiting.

It was supposed to be a small gem of a park on Biscayne Bay, a four-acre sweetener if voters agreed to allow the Miami Heat to build its new arena on public land. Parcel B, as the wedge of waterfront property is known, was one of the ways the arena deal successfully was sold to voters back in 1996.

Tucked behind a modern white arena, within sight of downtown, the park was supposed to be a place for residents to glory in the same waterfront views that are too often reserved for millionaires and, increasingly, billionaires.

Voters bought the rhetoric. But we were played. An unbelievable 26 years later, we’re still waiting for that park to become reality.

There are indications it might finally happen, or at least some version of what was promised. There are serious talks between Miami-Dade County and the Heat, both sides say. But after more than two decades, we’re no longer the gullible residents of 1996 who put their faith in pretty-colored renderings and the aw-shucks appeal of new Heat coach Pat Riley, back when he still had dark hair. We won’t believe it until we see it.

Parcel B is just a handful of acres. Not much in a city that calls itself the “Gateway to Latin America” or, more grandly, the “City of the Future.” Not much in a place where a developer is now building a skyscraper 100 stories high, the tallest in Florida. Not much — but still a promise, to us, the taxpayers. There are now about 60,000 people living downtown, but Parcel B remains little more than a fenced-off parking lot with a view of the water. The arena, of course, is in its third decade.

Disregard for voters

In the panoply of lies that South Florida has endured through the ages from its elected officials, the failure to actually provide a park on Parcel B doesn’t come close to the top of the list. That honor may well still go to the Miami Marlins stadium, a terrible deal financed with about $500 million in bonds back in 2009 that will wind up costing taxpayers as much as $2.4 billion by most estimates — and still hasn’t revitalized the area around it.

But the disregard for what voters were promised on tiny Parcel B in some ways rankles even more, precisely because it is such a small thing; 26 years of insults, even little ones, pile up. And because those who were in charge of making it happen brushed off that promise as though it meant nothing and are now, for the most part, gone from positions of power.

In some ways, Parcel B is a symbol of so much that is absurdly wrong with Miami. We talk a good game about investing in the community to build something great, but over and over, our leaders succumb to the latest person swaggering into town with bulging pockets. And whatever was said five years ago, or last month, wafts away on the ocean breeze. For those here for the long haul, that hurts. And even for those who alight here for just a year or two, such short-term thinking erodes the quality of life.

Miami deserves better. Miami should be better. Miami can be better.

It sounds like ancient history, but in 1996, the question of a new Heat arena downtown was thought to be a potential turning point for a city and a region striving to be taken seriously. There was good reason to worry: Miami was broke, its bond rating tanking and a humiliating state financial oversight board in the offing. The city and county governments were weathering damaging corruption scandals. Operation Greenpalm, as a federal investigation was dubbed, involved a bribes-for-bonds kickback scheme that would eventually take down a host of city and county leaders. The race riots of the ‘80s weren’t that far in the past. Neither was the Mariel boatlift.

With that roiling backdrop, a coalition of powerful community leaders got together — including the chairman of the Miami Herald’s parent company at the time, P. Anthony Ridder of Knight-Ridder — to sell county voters on the idea of a sleek new waterfront arena for the Heat. The team, owned by cruise ship mogul Micky Arison, had been threatening to move to neighboring Broward County, like the Florida Panthers hockey team.

There were serious objections to the new basketball arena plan. It would replace another — a round pink building named the Miami Arena — that was only eight years old and a few blocks inland, and that taxpayers were still paying for. Adding to that dicey proposition, the new arena would go on land that was supposed to be used for a big public park. Voters, understandably, were reluctant to subsidize a project that would benefit a billionaire team owner and multi-millionaire players.

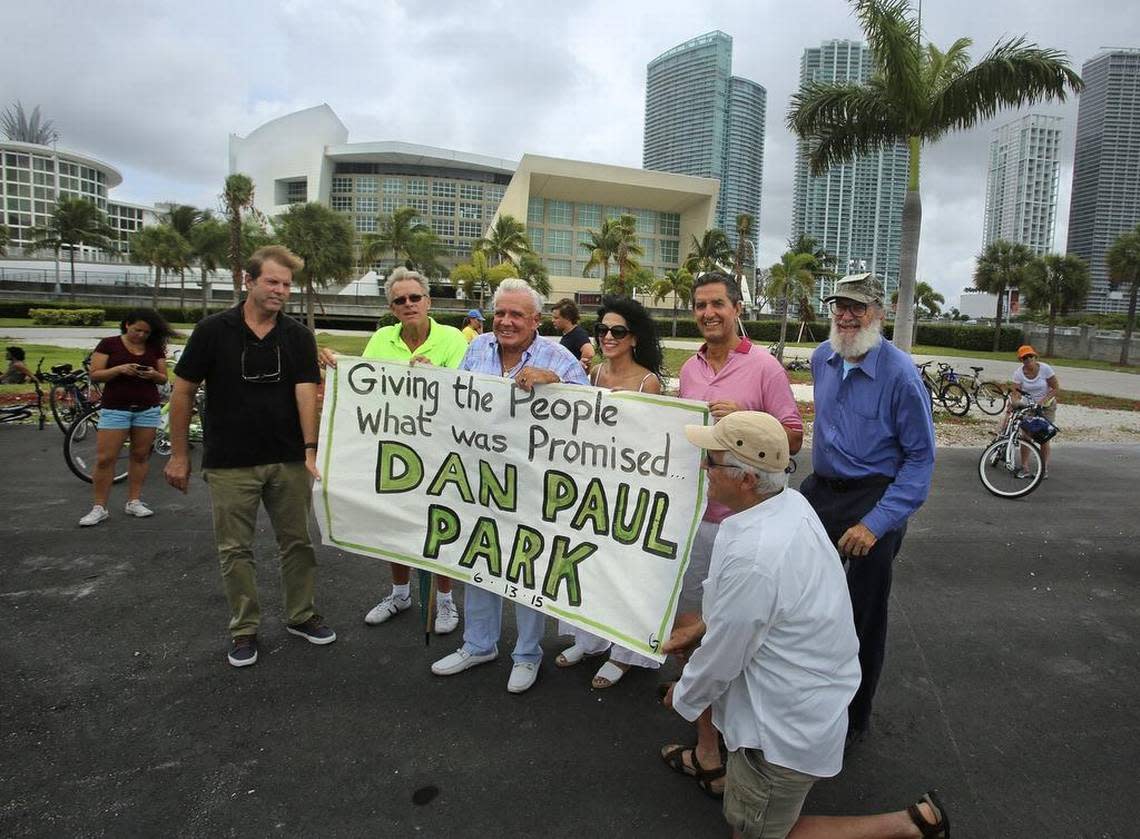

The County Commission approved the deal to put the arena on the waterfront property, but opponents — led by the late Dan Paul, an attorney and open-space activist — gathered enough signatures to force the issue onto the ballot.

‘Fantastic’ waterfront park

When it looked as though the referendum might not pass, the Heat agreed to pay the entire cost of the arena construction and launched an ad campaign that emphasized the lovely park voters would get out of the deal. The Miami Herald, in October 1996, ran a story about one ad, paid for by a political committee formed by the Heat, in which the Heat’s president made the pitch. In it, Riley appears on a basketball court, ball in hand: “If anybody tries to tell you the waterfront arena is only about basketball, hey, you got to get the facts. It is all about turning this into a fantastic new waterfront park for all of us to enjoy. With new shops, new restaurants and new excitement. Hey, Miami is a world-class city, so let’s go for the best with a world-class waterfront.”

The ad, which included renderings of frolicking children, soccer games and passing sailboats, concluded with a narrator’s voice: “For Miami’s future. A new waterfront park all our families can enjoy. Let’s build the best for Dade County.”

Voters ultimately went for it. But there was a loophole. The ballot language didn’t actually specify that the park would be built — a critical omission, it turned out. Once the referendum passed, the promise of a park melted away like an ice cube on a South Florida sidewalk in August.

We are all living with the consequences of that oversight — if that’s what it was. Though activists and some public officials — notably, former County Commissioner Audrey Edmonson — have continued to fight for a park, there’s still no such thing on Parcel B, which the Heat returned to county ownership in 2003. It remains a pseudo parking lot, which the team still uses — renting it from the county by the day, mostly for VIP vehicles on game and event days.

Make no mistake. Parcel B is a gorgeous spot. Windswept, commanding a broad view of the bay, it would make a glorious park. It’s not particularly visible or easy to get to, but Bayside Marketplace is directly south, within easy walking distance along the water. On a recent day, the gates at both ends were guarded because the Heat had rented the property. Still, a few people fished from the seawall, enjoying a view that few in Miami have been able to see.

As Peter Ehrlich of Miami’s Urban Environment League, an activist group, told us, “The fact that this taxpayer-owned waterfront site has been covered in concrete and asphalt for over 30 years is a crime.”

There have been a few slight developments. In 2017, the land got a light sprucing up, with new palm trees and benches and light posts, and in 2020, the property was officially named Dan Paul Plaza.

Still, Paul, who died in 2010, would be appalled, no doubt. He was a champion of public access to bayfront land — and he specifically opposed building the Heat’s tax-subsidized arena on county land. He also advocated for a bayfront pathway that would allow everyone, not just the affluent, access to the waterfront that helps define Miami. We’re sure that a fenced-off parking lot with a narrow span of grass and a paltry number of palms are not anything he would have been proud to attach his name to.

And even that sorry excuse for open space hasn’t always been guaranteed. For a while there, every few years brought another attempt to use what is still a prime piece of waterfront land. Retail stores, a 55-year lease for a Cuban-exile museum, a portion of a special-event auto race course — everything but a park.

Still open space

There is one saving grace. Through it all, the land has essentially remained open space, even in development-frenzied Miami. It can still become the park it was supposed to be.

We asked the Heat if they had any new plans for the land. They responded that they have “been working closely” for two years with Miami-Dade Mayor Daniella Levine Cava’s administration, a neighborhood association and others “to develop a plan for Dan Paul Plaza that addresses all our needs. . . . As part of our long-standing partnership with Miami-Dade County, [the] arena makes limited use of Dan Paul Plaza as needed for games, concerts, etc., for which Miami-Dade County as owner of the parcel is compensated. Absent that arrangement, we would not be able to meet our contractual obligations to Miami-Dade County to run a first-class facility and attract world-class events.”

But allowing the Heat to use that land for parking or staging events wasn’t part of the deal with taxpayers, who — it bears repeating — already have allowed a for-profit organization to build its arena on choice bayfront land owned by the public. How the team manages its parking and staging is not a taxpayer obligation. The Heat made the original promise. Riley put his name on it. The team needs to make good on it.

Levine-Cava said earlier this month that she is “very, very close” to being able to announce a plan in the next few months that would move the Heat’s current parking strip away from the water and close to the arena building, freeing up much of the land for public use. She offered details: This would be a plaza, not a park, but it would include a waterfront promenade, playing fields and an area for dogs and possible strengthening of the seawall.

“So everybody is on board. We’re all in agreement,” she said.

When Levine-Cava became mayor two years ago, she said she wanted to see a park there. We were glad to hear a current county leader declare that intention out loud — even though this agreement, if it actually happens, doesn’t sound like it will be everything promised. At the very least, we want to see those ugly fences near the water removed. But we expect a lot more.

The Heat should be responsible for providing its own extra parking. Taxpayers have been plenty generous already with the land — something most residents probably have long forgotten, if they ever knew it.

That’s the allure and the disappointment of Miami: a short memory. In a place known for transience, it’s easy to make fervent vows of action one year that are consigned to oblivion the next. But if you’re a long-term resident with greater expectations of your government — like Paul, Miami’s legendary warrior for public open space — each rosy promise tossed aside later is another reason to disconnect, to stop investing in our community, to distrust our leaders, ills that are plaguing our society more and more.

Turning Parcel B — or Dan Paul Plaza — into the sun-drenched public space that was dangled so tantalizingly before voters in 1996 won’t magically restore the electorate’s faith in government or undo the last more than two decades of broken promises.

But there is a basic wrong here that still needs to be righted. Voters 26 years ago cast their ballots in good faith, as government officials, community leaders — including the Miami Herald Editorial Board — and the Heat lined up to tell them it was a great idea. They shouldn’t have had to examine the referendum with a lawyer at their sides or act like eagle-eyed detectives on alert for a bait-and-switch.

We know the people in office in Miami today aren’t the ones who were here back then. Our current leaders didn’t break this promise. But it’s up to them to honor it anyway. Levine-Cava seems to understand that, at least.

There was another ad back in 1996 that described the situation this way: “Miami’s downtown waterfront: broken concrete, nobody uses it. Let’s make a change for the better. A new, world-class waterfront park with shops, restaurants and a championship arena. A new safe place for all our families to enjoy. A waterfront park we can all be proud of.”

Voters of Miami held up their end of the bargain. That “waterfront park we can all be proud of”? We’ve waited long enough. If elected officials want voters to believe their word actually means something and if teams like the Heat and owners like Arison still want that all-important community backing, they need to keep their promises — even the small ones.