Breaking the cycle: How local schools plan to fight summer hunger

Among the iconic images of the pandemic were thousands lined outside food banks and pantries during the nationwide shutdown.

The federal government provided funds and food through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) program; individual donors poured money into communities.

“Life on the margins is less troubling when there’s food on the table,” acknowledged Salvation Army Social Services Coordinator John Creaser. “Still, we depend on locals to provide financial support for the services we offer.”

According to Creaser, the pantry has been spending more on food and fuel to pick up donations. Not to mention, he added, the retraction of post-pandemic federal support.

As inflation continues, and benefit programs return to standard payment levels, advocacy groups fear another food insecurity crisis will implode.

In general, summer nutrition programs are administered by each state and operated in communities where at least 50 percent of children qualify for free or reduced-price meals during the school year.

School districts, local governments, faith-based organizations and nonprofits are among the sponsors, and they get reimbursed per meal by the USDA.

Any child 18 and younger can go to a site and eat at no cost.

"When school meals disappear, children find themselves hungry," said Creaser. "It impacts their health and can contribute to learning loss."

An exponential need for assistance

The Food Bank of Central New York covers an 11-county service area which includes Herkimer and Oneida County. They support 43 programs and are the primary distributor of food commodities to regional pantries, soup kitchens and emergency shelters.

As stated by Food Bank of Central NY Director of Community Impact Michael Watrous, partner agencies across the Mohawk Valley continue to report increased requests for services.

“The cost of fresh produce, dairy and protein remains high and many individuals are seeking assistance through our programs: Fresh Foods, Food Sense, and the Mobile Food Pantry,” said Watrous. “Since November we’ve assisted over 50,000 individuals each month. This marks a 13.79% increase from last year.”

With schools approaching summer recess, Watrous said many will rely on summer food service programs to help with weekday meals and fill in gaps in the family grocery budget.

The Central NY Food Bank plans to publish summer food distribution site information on its website later this June.

“The high rate of child poverty in this area makes summer nutrition programs more important than ever,” Watrous emphasized. “For the first year students eligible for free and reduced lunches will also be eligible this summer for the P-EBT program, which provides $30 in SNAP benefits per child. Parents interested should contact their school’s district food service director.”

Community Eligibility Provision (CEP)

Oneida-Herkimer-Madison (OHM) BOCES Director of Shared Food Services Kathleen Dorr pointed out an uptick in assistance since the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), a meal service option for School Food Authorities (SFA), was enacted this fiscal year.

“Kids across Oneida, Herkimer and Madison county rely on school meals for a significant portion of their daily nutrition – breakfast and lunch,” said Dorr.

She highlighted the contrast between meals served this year compared to last: in 2023 OHM Boces served 2,300 breakfasts daily; in 2024 3,990 breakfasts were served daily.

Last year 6,030 lunches were distributed daily; this year: 7,350.

“Food insecurity exists, even within families that don’t qualify for support,” Dorr claimed. “This is a difficult economy for all income levels, since general expenses are so high. School meal programs are crucial for alleviating some of that burden.”

With support from the state's new CEP program, and the ongoing federal Child and Adult Care Food Program (CAFP), OHM public schools serve breakfast and lunch daily. Many families that fall into income qualifying areas are also offered access to an after school snack program.

Dorr mentioned that while some schools have privately funded backpack programs, sending students home with food during the weekend, that option is not yet available through any current federal or state nutrition programs. Moving forward she said that distributing dinner and/or weekend meals would prove beneficial.

Hunger takes no summer break

Dorr shared that one of the positive things to come from the pandemic was the amount of assistance readily available as she felt it “helped to remove existent stigmas.”

“Families used to be able to pick up meals and bring them home,” explained Dorr. “Sometimes we could distribute five days-worth of meals at a time. The regulations have since adjusted and now encourage congregate feeding, meaning that meals are to be enjoyed on site premises. For rural residents that’s not always practical, so we’re looking at better ways to allocate our resources.”

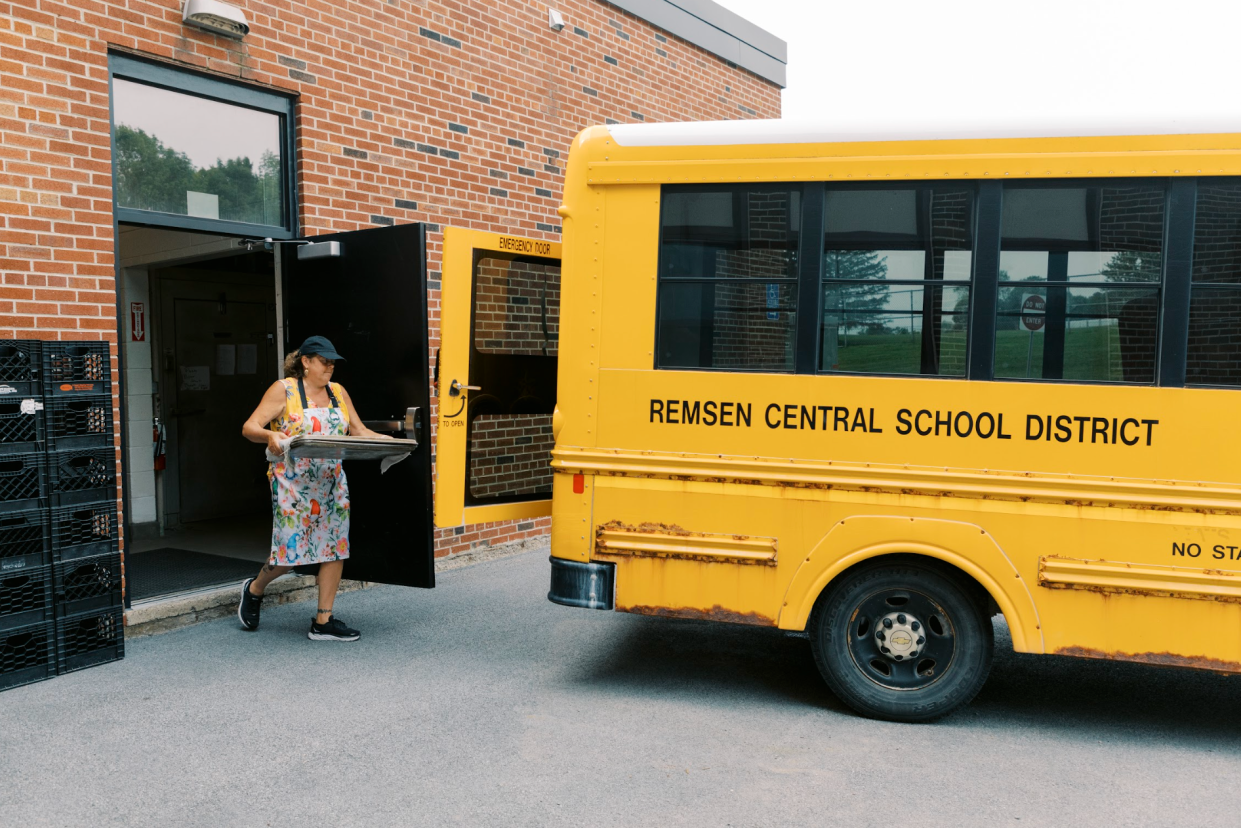

Dorr pointed out how hunger takes no summer break. She outlined a few options for families from July through September.

Many schools offer academic enrichment programs – commonly referred to as “summer school” – where eligible and enrolled students are able to access to free meals.

Income eligible municipalities – either because of census data or because the district itself is 50% or more free or reduced qualified – also offer open summer food service programs. Any student 18 and under can grab a meal.

The BOCES program typically hosts 15 summer sites region wide.

“We often see a barrier where kids can't pick up food if they aren’t enrolled in a summer program,” said Dorr. “We want to increase participation so everyone in the community has access to communal sites. Come one, come all, no questions asked. That’s the goal.”

'We need communal support'

Watrous, Dorr and Creaser agreed that feeding the community is an “all hands on deck” ordeal.

“In times like these, when money is tight and streams of funding are reduced, it's easy for our hearts to harden,” sighed Creaser. “We need to fight against that. Many not-for-profit agencies, hospitals, and churches are seeking volunteers. We are grateful for those who sign up; the need in this community just seems to grow.”

Local food banks and pantries are constantly trying to develop new initiatives and youth programs but most rely on endowment.

“Donations directly fund what we’re able to offer,” Creaser stressed. “We need communal support.”

This article originally appeared on Observer-Dispatch: Mohawk Valley school districts take aim at summer food insecurity