Brazil floods drive thousands from their homes

"When I left for work on Monday, I could still get through the water-logged street with my car. By the afternoon, the army was rescuing people with a truck," says Porto Alegre resident Magda Moura.

That was the day that the floods which have devastated parts of southern Brazil cut off the building she lived in.

"By Wednesday, the water had reached [a height of] 1.7m (5ft 6in)," she recalls.

The 45-year-old physiotherapist is one of 408,100 people who have been displaced by floods triggered by torrential rain in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul.

At least 116 people have died across the state and, with many towns still cut off by the flood waters, hopes of finding the more than 140 people who are still missing are dwindling.

Much of the state capital, Porto Alegre, has been plunged into darkness by the flood, which has damaged power and water treatment plants, also leaving most residents without drinking water.

Magda, 45, and her husband, 49-year-old Angelo Tarouco, spent two days rescuing neighbours cut off by the flood waters which surrounded their high-rise buildings.

"Of all the occupants of the towers, only a young couple remained on the premises," she says.

The couple told her that they had enough provisions to last them for a week but with food and water scarce in the city she cannot help but worry about them.

About 70,000 people are living in temporary shelters. Roselaine da Silva is one of them. She is staying in an evangelical church with her three children, one of whom has autism. Their two dogs are with them, but she says she's had to leave her two cats behind in her flooded Sarandi neighbourhood.

"I didn't know the water would take over like this," she says, her voice choked with emotion. "I've cried so much, blaming myself for leaving them in what I thought was a safe place."

In her makeshift bedroom in the church, Roselaine - surrounded by donated clothes and other displaced families - says she has found some comfort in the support of strangers who have opened their doors to those in need.

In the northern zone of the city, the evangelical church has become a lifeline for dozens of families like Roselaine's huddled in the halls.

They too have lost everything to the floodwaters, their homes submerged, their possessions destroyed.

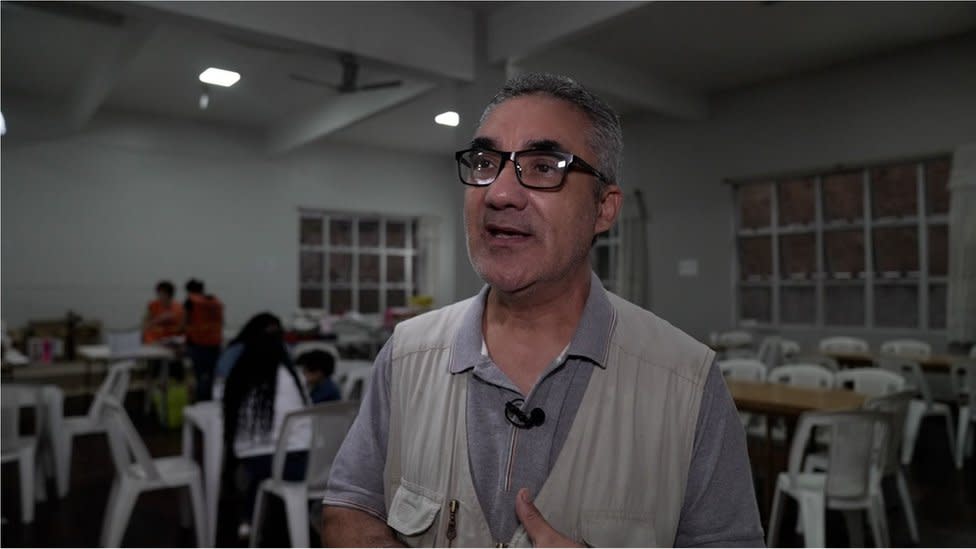

Pastor Dari Pereira, overwhelmed by the influx of displaced people, says he is doing his best to provide for everyone's needs.

"We offer four meals a day, hot showers, medical and psychological assistance," he explains, his voice weary but determined. "But the demand keeps growing, and we ran out of space. We now have to relocate people to other shelters."

He believes it is important to offer shelter not only to people but also to their pets, adding that it is crucial for families' emotional healing.

"We didn't separate people from animals because separating them would take away everything they had," he says.

"Today the vet said these animals could not stay inside because of the risk of transmitting diseases. But the school across the street has given us the gymnasium so we can build a kennel and a cattery."

While some volunteers stockpile water, others sort donated clothes by size, and part of the team distributes the dozens of hot meals that have just arrived, also as donations.

Given the extent of the devastation, Marcelo Dutra da Silva, professor of ecology at the Federal University of Rio Grande (FURG), says that this time the public response needs to change radically.

"It's no use trying to rebuild everything that was destroyed in this current event trying to make it as it was before. That doesn't work any more."

According to Mr Dutra da Silva, the reconstruction of Rio Grande do Sul will need to be planned by taking into consideration which areas are safer and more resistant to extreme climate variations and which are here to stay.

"Entire cities will have to change location," he says.

"It is necessary to move urban infrastructures away from these higher-risk environments, which are the lower, flatter, and wetter areas, the hillside areas, the riverbanks, and the cities located within valleys."

But the road ahead will be long and difficult. The flood crisis has left neighbourhoods isolated, with residents struggling to access basic necessities like food and clean water. The city's infrastructure has been severely damaged, and it will take months, if not years, to recover.

The continuous rainfall is a constant reminder of the fragility of life in this flood-prone city. The fear of further flooding looms large, casting a shadow over the already devastated communities.

Despite the devastation and despair, there are glimmers of hope. Churches, community centres, and volunteers have been coming together to provide support and assistance to those in need. Donations pour in from across Brazil, and people from all walks of life are lending a helping hand.

As Roselaine watches her children play with other children displaced by the floods, she refuses to give up hope. "We've lost so much," she says, her voice wavering but resolute.

"But we still have each other, and as long as we have that, we can face anything.

"We will rebuild," she says. "We'll come back stronger than ever."