Black 30 and under: Florida’s attack on Black history an attempt to ‘erase our existence’

Ebony Felton has got a lot to say.

As the 18-year-old effortlessly weaves through topics like a master seamstress, it’s difficult to forget she’s still very much a teenager. There’s a clear burgeoning wisdom forming here. On the topic of education, she’s inquisitive. On the topic of Liberty City, her hometown, she’s optimistic. On the topic of Miami Northwestern, her high school, she’s a beacon of school pride, belting out a little “Go Bulls” towards the end of the interview.

There’s one part, however, that offers some clarity about the gap between Black students like Felton and Florida Department of Education officials, which The New York Times recently reported asked if the College Board was “trying to advance Black Panther thinking” in conversations about the Advanced Placement African-American Studies course.

“I have not seen a textbook about Fred Hampton in school,” she said, referring to the deputy chairman of the Black Panther Party’s Illinois chapter, whose message about unity among all oppressed people lives on despite Hampton being gunned down by Chicago police at just 21 years old. Felton also added that she wanted to learn more about Black women and LGBTQ+ historical figures, the last of which likely won’t happen anytime soon as the College Board removed references to Black queer theory from the AP African-American studies curriculum.

That the Northwestern junior even knows about Hampton is a testament to Power U, an organization that Felton volunteers with in order to learn the necessary skills to make change in her community. As Felton speaks, she’s flanked by a mural on the side of Power U’s building depicting women holding signs reading “Yes We Can” in English, Spanish and Haitian Creole that’s painted blue like an ocean of possibilities. This space, like many others throughout Miami-Dade County, affords Black Miamians the opportunity to reimagine a better Florida, one where their history isn’t under attack by Gov. Ron DeSantis.

“He’s a white man in Florida, one of the most expensive states to live in, and I don’t think he understands what Black people go through and he doesn’t care about Black people,” Felton said, referring to DeSantis.

Across the street from Power U sits the Roots Black House, a building that actually bears Hampton’s face alongside a depiction of the 1968 Black Power Salute, a Black Wall Street historical marker and an homage to fallen rapper-activist Nipsey Hussle. As the mural suggests, there’s a little bit of everything inside: a print shop, Roots’ own apparel collection, an event space, rooms rented for small businesses and a bookshelf with hundreds of books about the Black experience, Black wealth — you name it.

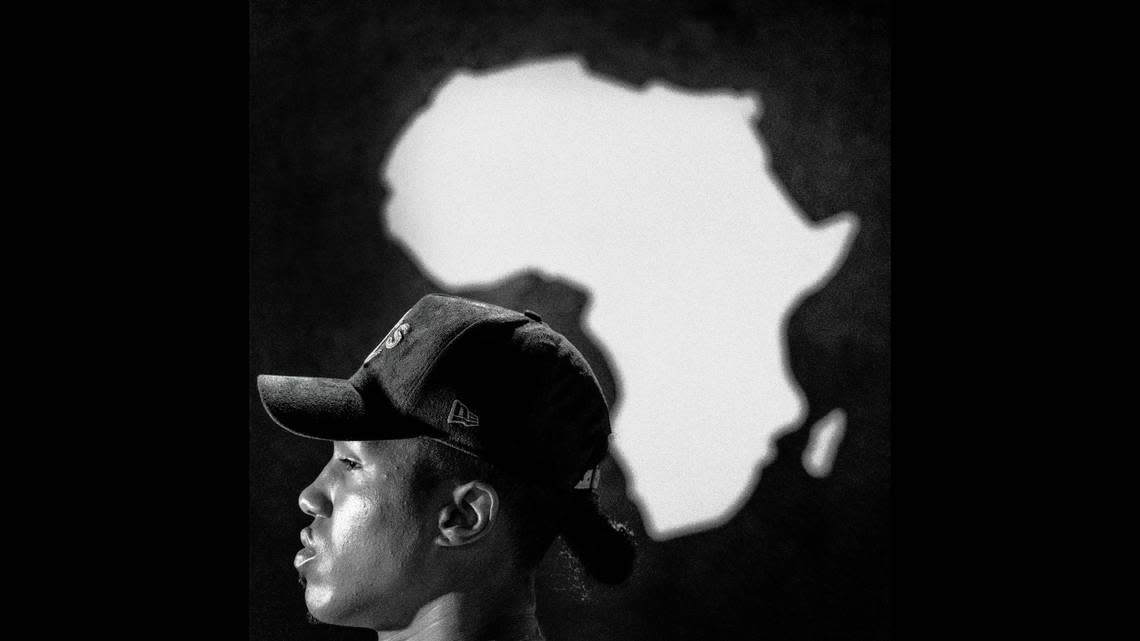

“Everything here is geared towards educating people of the Black community about the Black community, helping the Black community,” King Hoodie, a North Miami-born rapper and author, said of the Roots Blackhouse. He never felt more comfortable expressing his Blackness in his 29 years in Miami than in this space, he said.

“If all of us can identify the common problems in our community that’s attacking each and every one of us — whether it be depression, drug addiction, distractions, violence — we can all collectively come to a solution” here.

Born Jean-Raymond Jean Philippe to a Puerto Rican mother and a Haitian father, the North Miami Beach High graduate says he grew up in the Miami before being “Haitian was cool.” His birth name meant that everyone saw him as Black and Haitian first, even though his father never taught him Creole. Growing up in Miami with such a distinct, mixed heritage instilled in him the importance of unity in the fight against oppression. That the DeSantis administration even got involved at all with the AP African-American course baffled Philippe.

“The curriculum should be strong and created by people who actually fight for this community on a daily basis,” Philippe said, advocating for the inclusion of activists’ voices rather than that of the government. He later called the DeSantis administration’s opinion that the AP African-American course “lacks educational value” simply “ridiculous.”

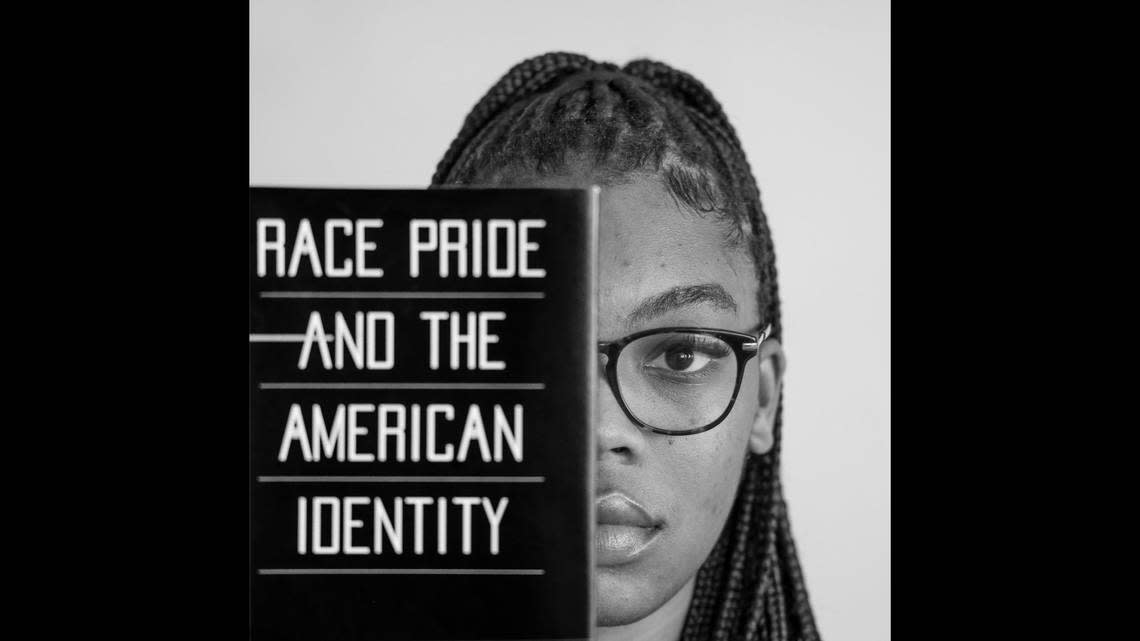

University of Miami senior Lauren Lennon, 21, felt similarly about DeSantis’ attack on Black history, calling it an attempt to “erase our existence.” In addition to serving as the president of United Black Students, she’s also the diversity, equity and inclusion director of UM’s student government association. DEI also happens to be an area that DeSantis has taken issue with as he recently announced plans to bar state universities from funding any such initiatives. UM won’t be affected due to it being a private institution.

“My main focus is reminding students of color and Black students that you belong here,” Lennon said, seated inside the University of Miami’s new Center for Global Black Studies, a place that she describes as a “space for us to learn, grow and build community.”

COVID-19 protocols and the movement for racial equality framed the first two years of her college, so the Reading, Pennsylvania, native wasn’t necessarily surprised by the Florida that she came back to in fall 2021. Lennon had seen how Black people were being represented in the news — something that made her switch her major to broadcast journalism — and, as she put it, had her eyes opened “to the evils of the world.” Ultimately, she believes DeSantis’ work does a disservice not just to Black Floridians but everyone.

“You can’t fully understand American history without knowing the struggles of Black people,” she said. “We served as the backbone of America for so long.”

For Reyna Noriega, a visual artist and author from South Miami-Dade, DeSantis’ discourse underscores the importance of not waiting for others to “save us.”

“No one is prioritizing us and so we have to prioritize ourselves and our community,” Noriega said. “We have to educate ourselves and share and build community.”

From the comfort of her Miami Beach home-studio, a place that she says is where she “gets to create the world I want to live,” Noriega talked about how her mixed heritage — she’s of Cuban and Bahamian descent — was difficult at times during her younger years when she felt forced to fit into a single box. In a sense, her art, which primarily depicts women of color without facial features, is both a celebration of both her roots but also a way to push back on traditional collectors who she believes prioritize work about “our trauma and Black portraiture.”

“It makes me feel like those collectors are looking at us like a spectacle, like you take a picture of a lion because you don’t understand it or you feel separate from it,” Noriega, 30, said. Again, she emphasizes the importance of creating “the art we want to see, the movies we want to see, the literature we want to read ourselves.”

The intentionality behind such creations is critical when considering how it may eventually find newly arrived Black Miamians like Florida Memorial University freshman Tyla Bartlett. Originally from the Bahamas, Bartlett has been on this side of the Atlantic Ocean for less than five months. And while she’s still educating herself about the ins and outs of Florida’s politics, she benefits from being at the region’s sole Historically Black College or University. HBCUs are known incubators for social change.

“This is a place where not only can I blossom but build personal connections and where I don’t feel like I have to walk on eggshells with my culture,” the 19-year-old Bartlett said, seated on the steps of FMU’s student services center.

Unlike her home country, the United States recognizes Black History Month. The lessons learned throughout February — as well as in her African American Studies course — have helped her better understand Black Americans’ “fight” for freedom.

“It’s very shocking to me that they had to go through all of that for us to live how we live today,” Bartlett said. “I’m glad that the States have a month for us to understand what it means to be Black.”